Catholics’ Church Attendance Resumes Downward Slide

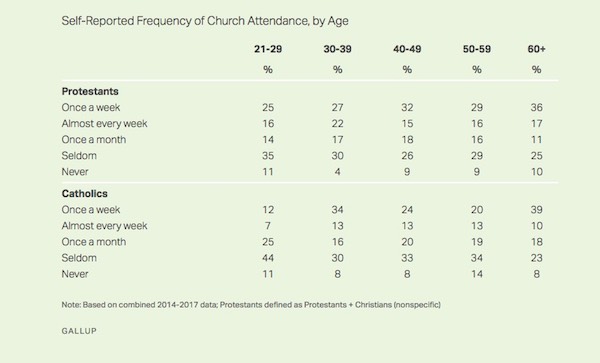

-

Fewer than four in 10 Catholics attend church in any given week

-

Catholic attendance is down six percentage points over the past decade

-

Protestant attendance steady, but fewer Americans now identify as Protestants

by Lydia Saad

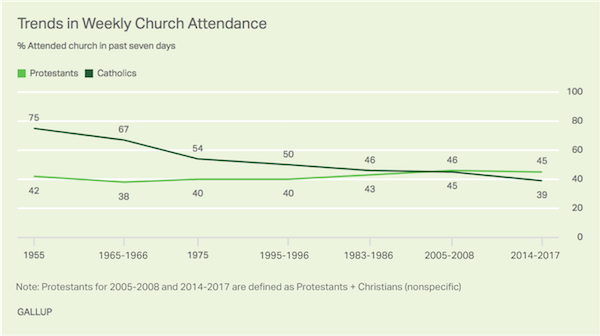

Weekly church attendance has declined among U.S. Catholics in the past decade, while it has remained steady among Protestants.

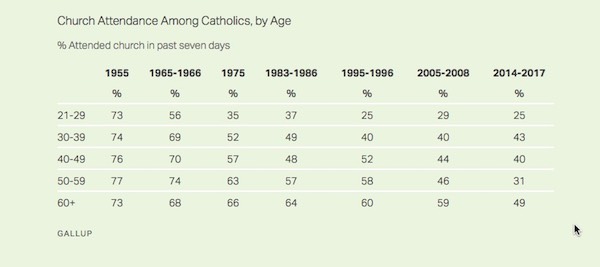

From 2014 to 2017, an average of 39% of Catholics reported attending church in the past seven days. This is down from an average of 45% from 2005 to 2008 and represents a steep decline from 75% in 1955.

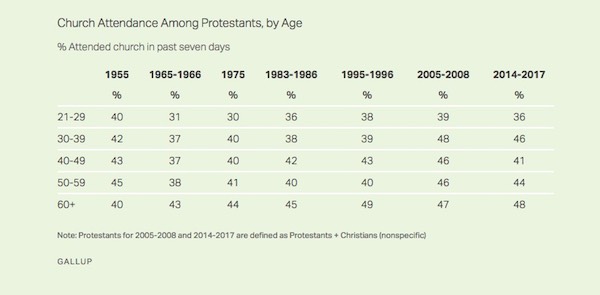

By contrast, the 45% of Protestants who reported attending church weekly from 2014 to 2017 is essentially unchanged from a decade ago and is largely consistent with the long-term trend.

As Gallup first reported in 2009, the steepest decline in church attendance among U.S. Catholics occurred between the 1950s and 1970s, when the percentage saying they had attended church in the past seven days fell by more than 20 percentage points. It then fell an average of four points per decade through the mid-1990s before stabilizing in the mid-2000s. Since then, the downward trend has resumed, with the percentage attending in the past week falling another six points in the past decade.

This analysis is based on multiple Gallup surveys conducted near the middle of each decade from the 1950s through the present. The data for each period provide sufficient sample sizes to examine church attendance among Protestants and Catholics, the two largest religious groups in the country, as well as the patterns by age within those groups. The sample sizes are not sufficient to allow for analysis of specific Protestant denominations or non-Christian religions.

Less Than Half of Older Catholics Are Now Weekly Churchgoers

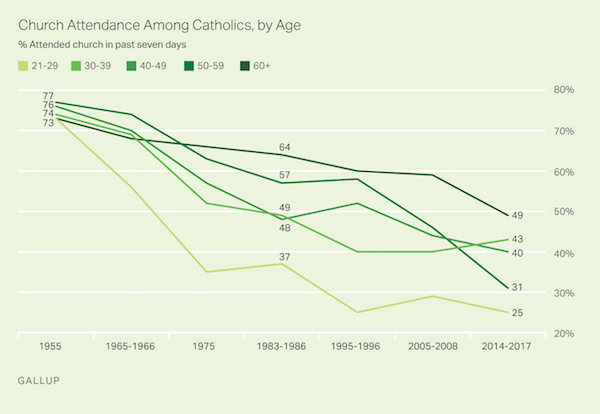

In 1955, practicing Catholics of all age groups largely complied with their faith’s weekly mass obligation. At that time, roughly three in four Catholics, regardless of their age, said they had attended church in the past week. This began to change in the 1960s, however, as young Catholics became increasingly less likely to attend. The decline accelerated through the 1970s and has since continued at a slower pace. (See tables at the end of this article for all trend figures.)

Meanwhile, since 1955, there has also been a slow but steady decline in regular church attendance among older Catholics. This includes declines of 10 points or more in just the past decade among Catholics aged 50 and older, leading to the current situation where no more than 49% of Catholics in any age category report attending church in the past week.

To maintain consistency with earlier Gallup polling when the sample population was age 21 and older, this analysis defines the youngest age group as those aged 21 to 29 rather than the 18- to 29-year age range typically examined in modern polling.

Attendance Holding Up Among Protestants of All Ages

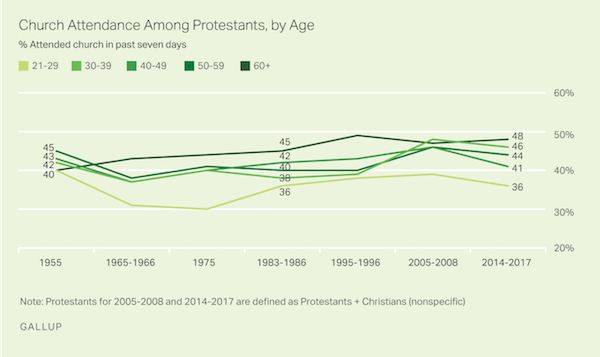

U.S. Protestants’ church attendance was not nearly as high as Catholics’ in the 1950s — but it has not decreased over time. Protestants’ church attendance dipped in the 1960s and 1970s among those aged 21 to 29, but it has since rebounded. Among those aged 60 and older, weekly attendance has grown by eight points since the 1950s. (See tables at the end of this article for all trend figures.)

Currently, the rate of weekly church attendance among Protestants and Catholics is similar at most age levels. One exception is among those aged 21 to 29, with Protestants (36%) more likely than Catholics (25%) to say they have attended in the past seven days.

Protestants’ Pie Is Shrinking Faster Than Catholics’

While attracting parishioners to weekly services is vital to the maintenance of the Catholic Church and Protestant denominations alike, so too is maintaining a large base of Americans identifying with each faith group.

Although the rate at which Protestants attend church has held firm over the past six decades, the percentage of Americans identifying as Protestant has declined sharply, from 71% in 1955 to 47% in the mid-2010s. Since 1999, Gallup’s definition of Protestants has included those using the generic term “Christian” as well as those calling themselves Protestant or naming a specific Protestant faith.

By contrast, while the Catholic Church has suffered declining attendance in the U.S., the overall percentage of Catholics has held fairly steady — largely because of the growth of the U.S. Hispanic population. Twenty-two percent of U.S. adults today identify as Catholic, compared with 24% in 1955.

A troubling sign for both religions is that younger adults, particularly those aged 21 to 29, are less likely than older adults to identify as either Protestant or Catholic. This is partly because more young people identify as “other” or with other non-Christian religions, but mostly because of the large proportion — 33% — identifying with no religion.

Bottom Line

After stabilizing in the mid-2000s, weekly church attendance among U.S. Catholics has resumed its downward trajectory over the past decade. In particular, older Catholics have become less likely to report attending church in the past seven days — so that now, for the first time, a majority of Catholics in no generational group attend weekly. Further, given that young Catholics are even less devout, it appears the decline in church attendance will only continue. One advantage the Catholic Church has is that the overall proportion of Americans identifying as Catholic is holding fairly steady. However, that too may not last given the dwindling Catholic percentage among younger generations.

Protestant church seats may also be less full, but for a different reason. Although weekly attendance among Protestants has been stable, the proportion of adults identifying as Protestants has shrunk considerably over the past half-century. And that trend will continue as older Americans are replaced by a far less Protestant-identifying younger generation.

All of this comes amid a broader trend of more Americans opting out of formal religion or being raised without it altogether. In 2016, Gallup found one in five Americans professing no religious identity, up from as little as 2% just over 60 years ago.

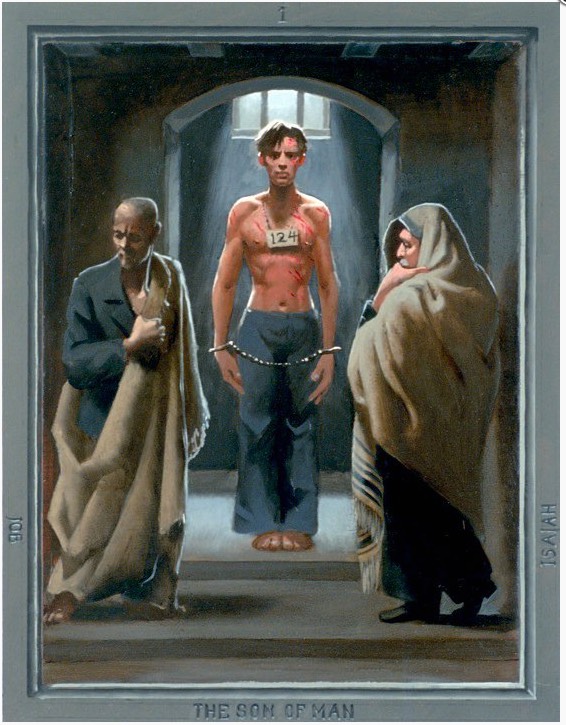

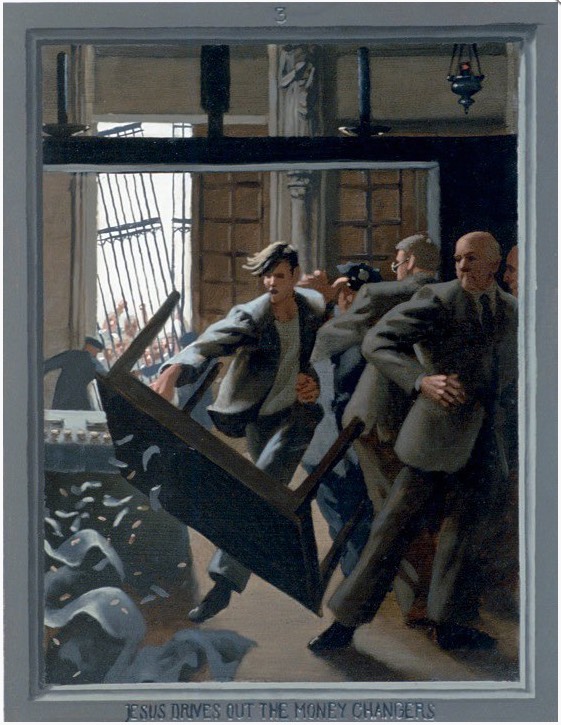

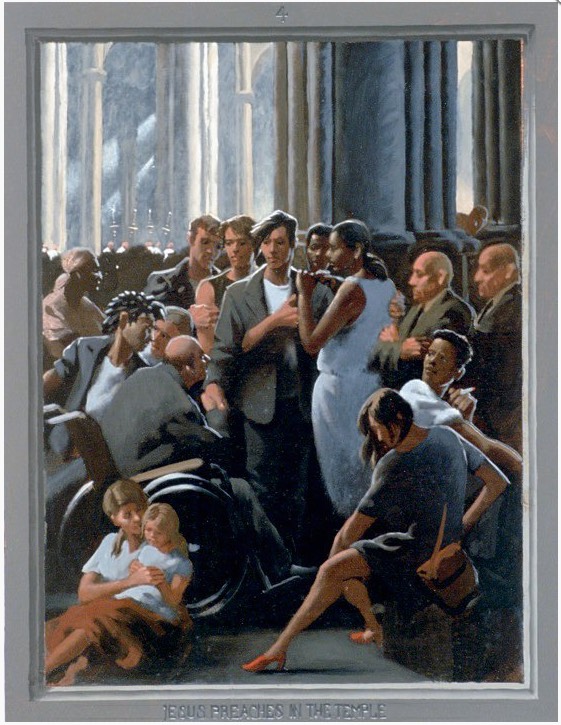

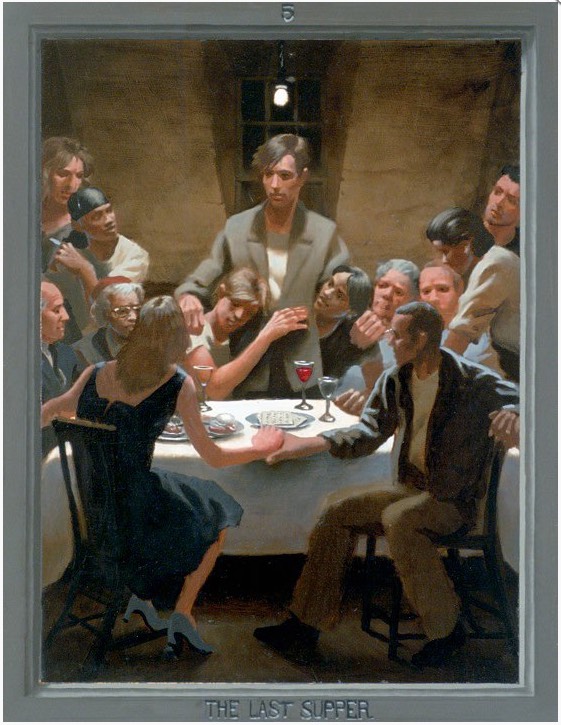

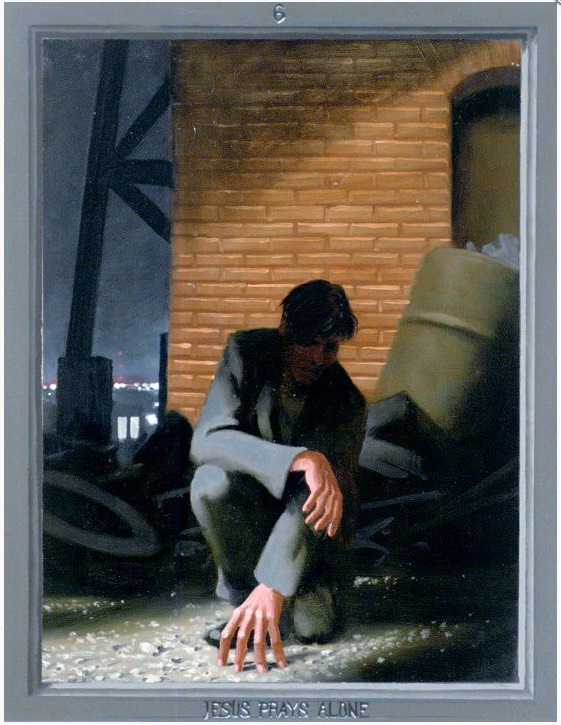

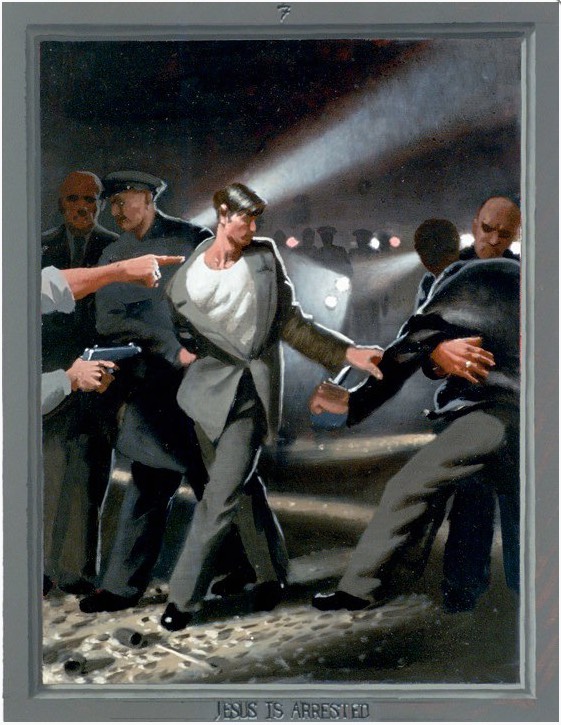

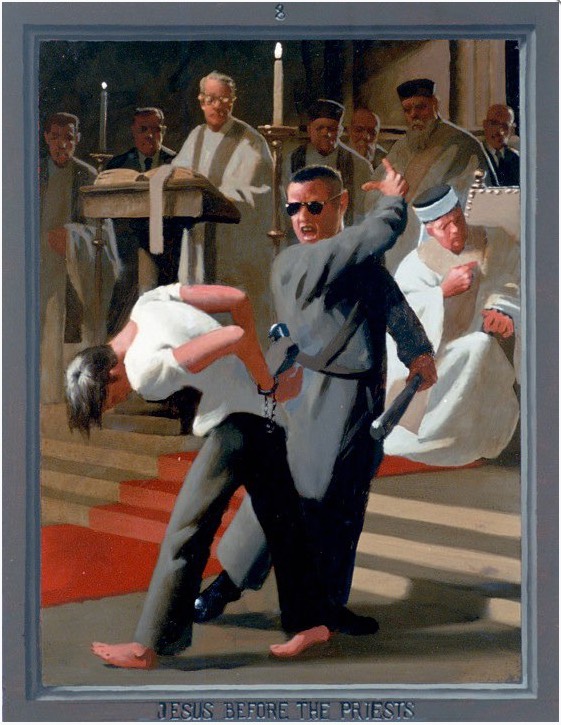

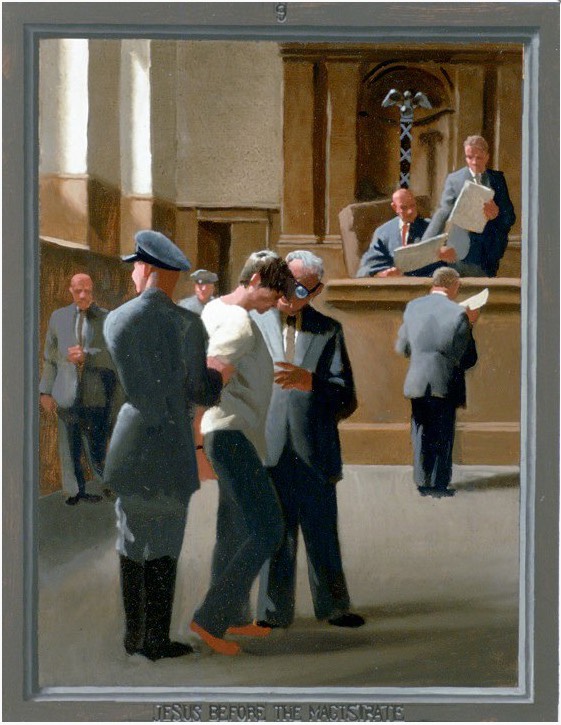

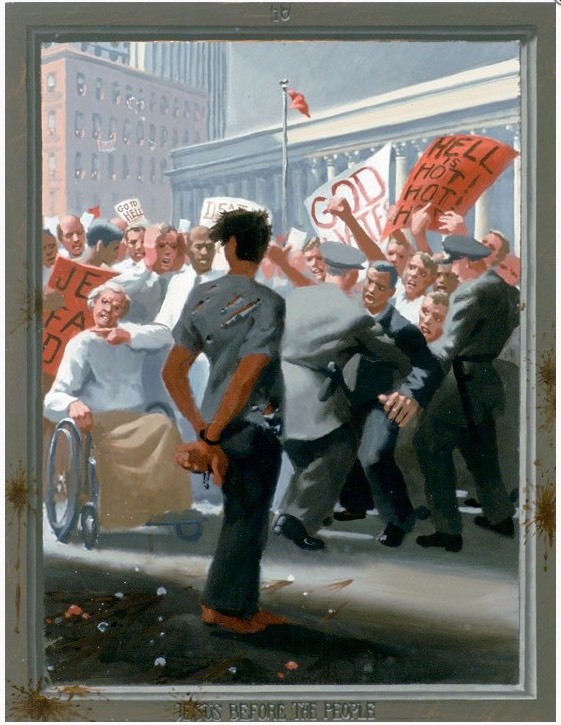

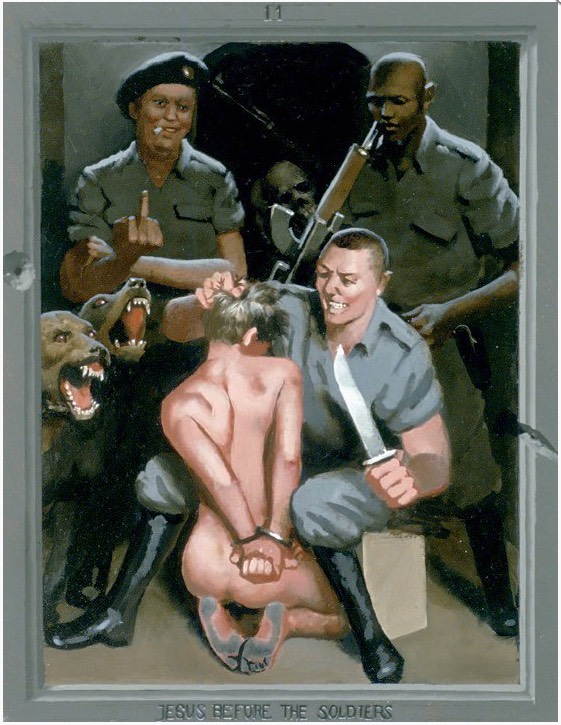

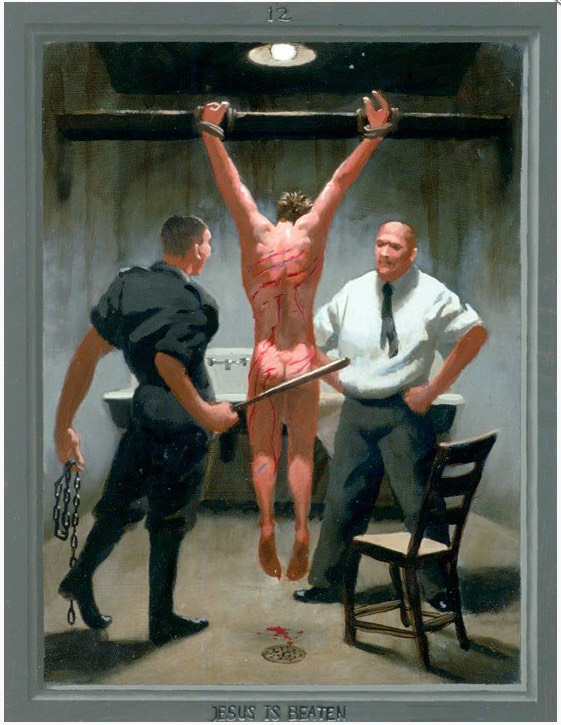

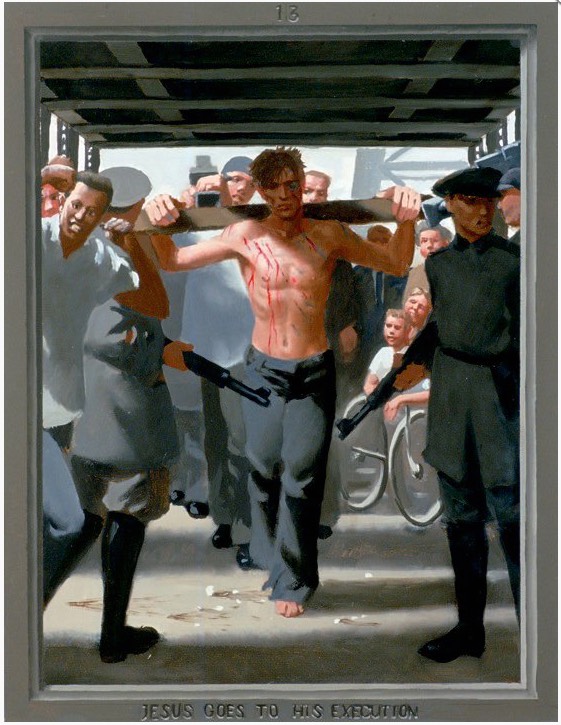

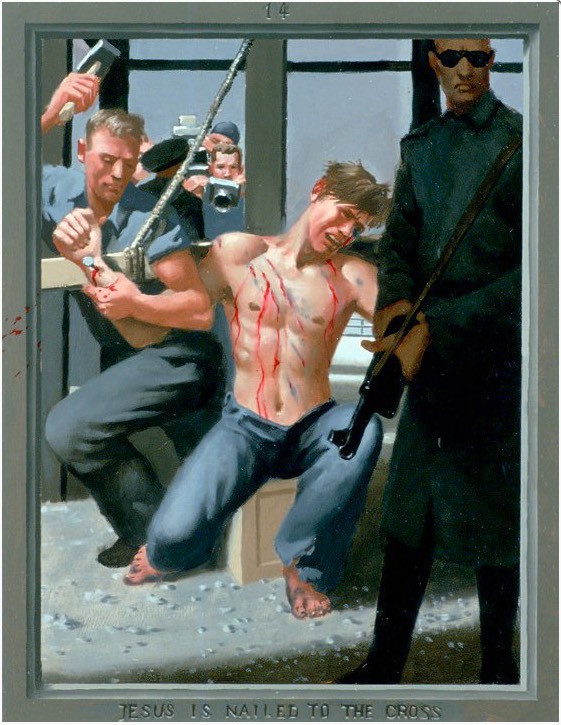

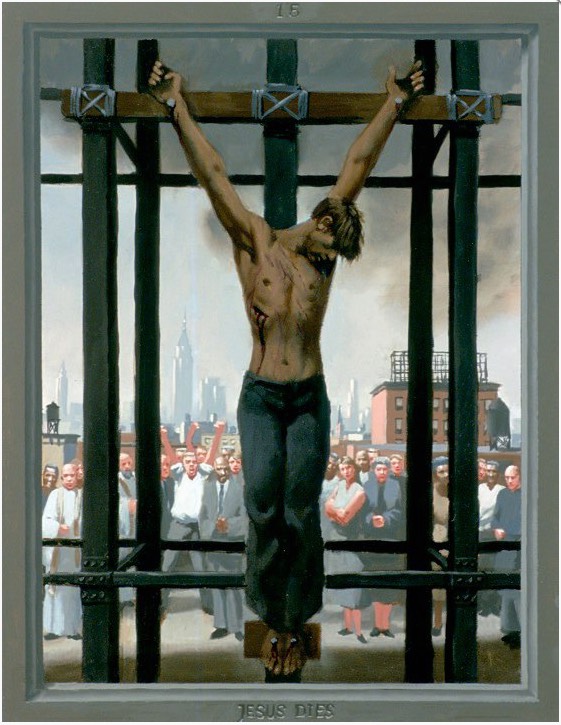

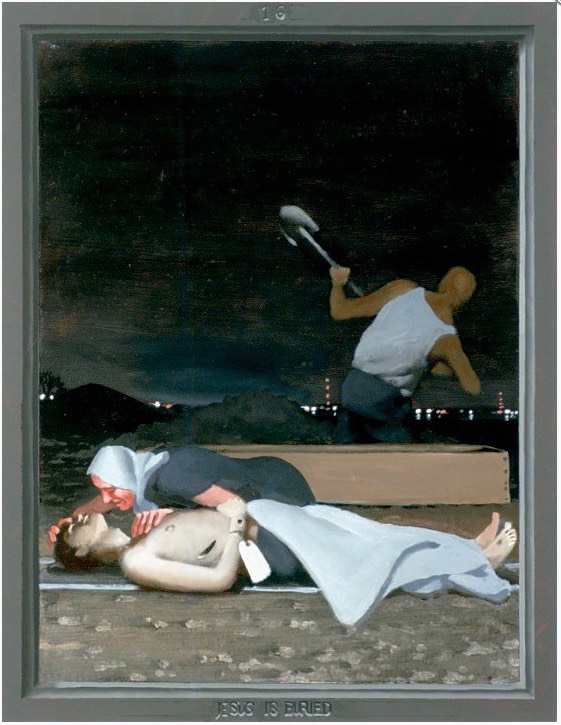

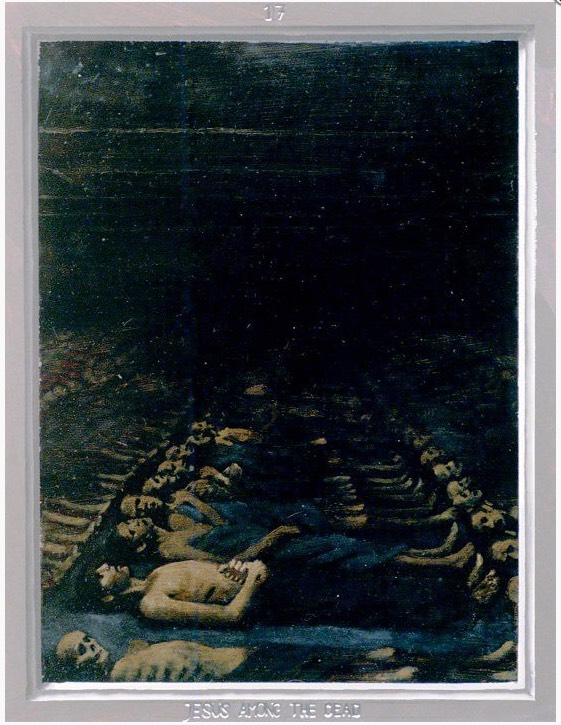

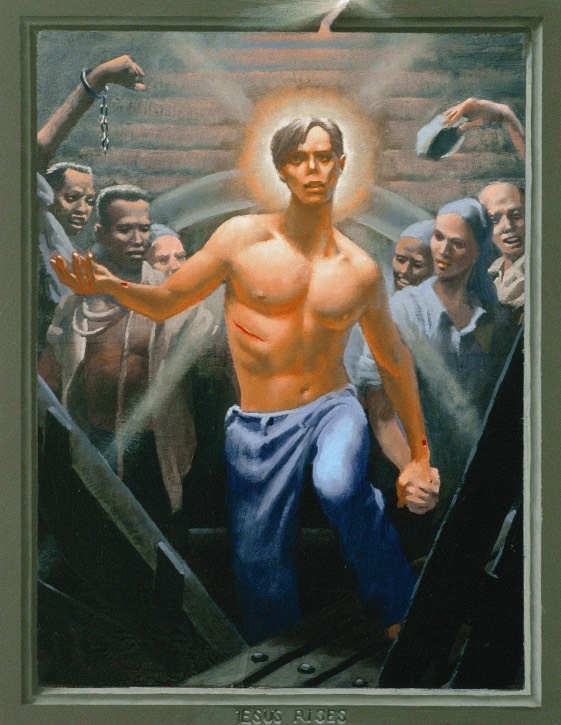

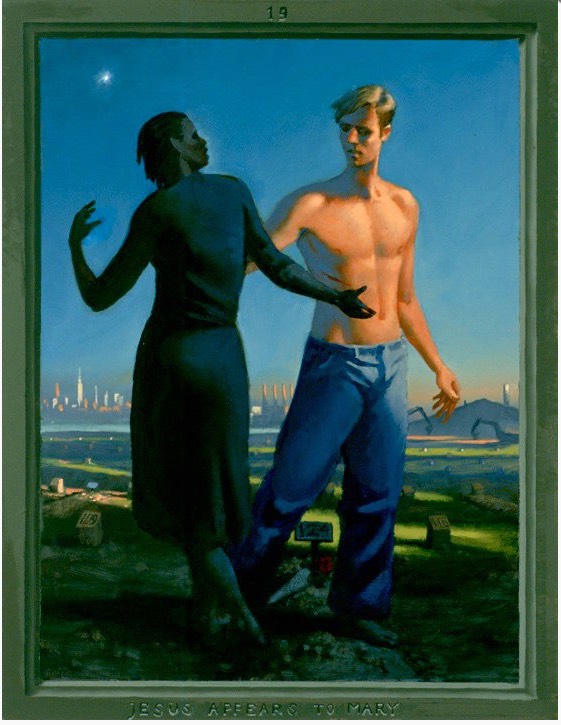

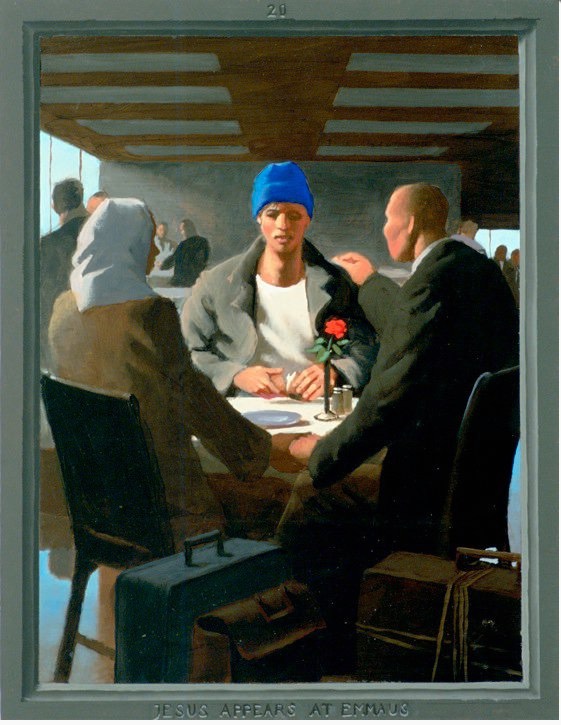

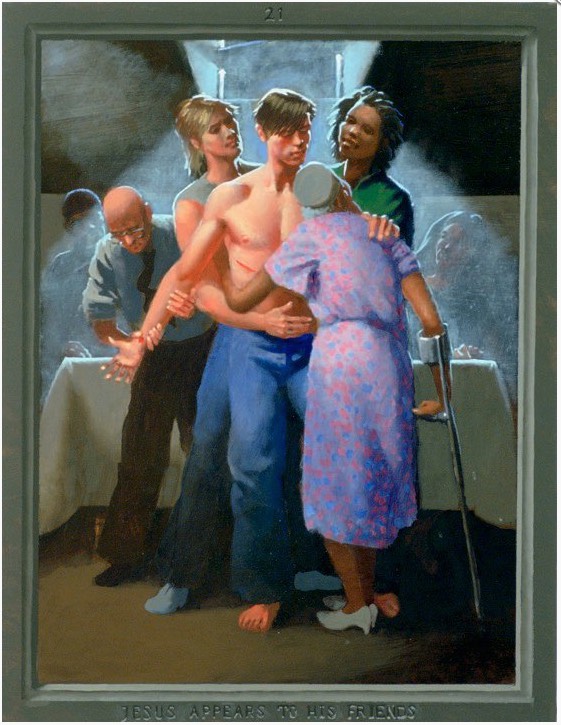

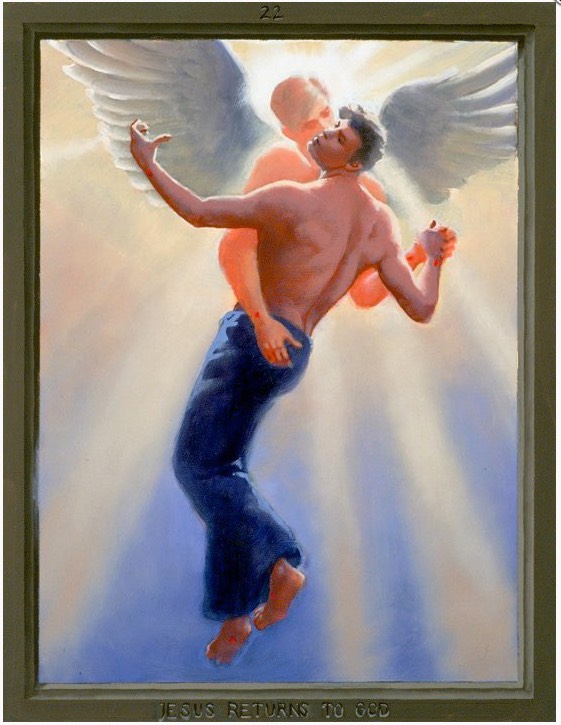

Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision

Paintings by Douglas Blanchard

A contemporary Jesus arrives as a young gay man in a modern city with “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision” by Douglas Blanchard. The 24 paintings present a liberating new vision of Jesus’ final days, including Palm Sunday, the Last Supper, and the arrest, trial, crucifixion and resurrection.

“Christ is one of us in my pictures,” says Blanchard. “In His sufferings, I want to show Him as someone who experiences and understands fully what it is like to be an unwelcome outsider.” Blanchard, an art professor and self-proclaimed “very agnostic believer,” used the series to grapple with his own faith struggles as a New Yorker who witnessed the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

High-quality reproductions of Doug Blanchard’s 24 gay Passion paintings are available at: http://douglas-blanchard.fineartamerica.com/ Giclee prints come in many sizes and formats. Greeting cards can be purchased too. Some originals are also available.

Visit Douglas Blanchard’s site ↪HERE↩!

Happy New Year 2018

We made it!

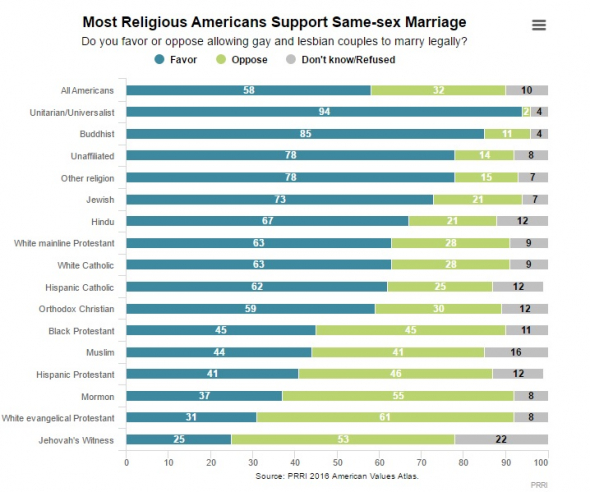

Most Religious Americans Support Gay Marriage, Poll Finds

By Samuel Smith

The majority of Americans who identify as religious say they favor allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry and oppose policies that would give business owners the right to refuse services to same-sex wedding ceremonies, according to data compiled by the Public Religion Research Institute.

Last Friday, the Washington, D.C.-based polling firm released a new analysis drawn from interviews with 40,509 Americans throughout 2016 for PRRI’s American Values Atlas.

The data, which has an error margin of less than 1 percentage point, finds that the majority of only three religious demographics — white evangelical Protestants, Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses — said they oppose “allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally.”

While 58 percent of Americans said they support same-sex marriage, 61 percent of white evangelical Protestants, 55 percent of Mormons and 53 percent of Jehovah’s Witnesses signaled that they oppose the legalization of same-sex marriage, which happened in 2015 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states cannot ban same-sex marriage, making it legal nationwide.

By comparison, only 28 percent of white Mainline Protestants and white Catholics, 25 percent of Hispanic Catholics and 30 percent of Orthodox Christians said they oppose allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry.

found that 54 percent of all Christians surveyed agreed that homosexuality should be accepted by society. Over half of all Roman Catholic, Mainline Protestant, Orthodox Christians and African-American Protestant respondents said they believe that homosexuality should be accepted in society, while only 36 percent of evangelical Protestants, 36 percent of Mormons and 16 percent of Jehovah’s Witnesses agreed.

found that 54 percent of all Christians surveyed agreed that homosexuality should be accepted by society. Over half of all Roman Catholic, Mainline Protestant, Orthodox Christians and African-American Protestant respondents said they believe that homosexuality should be accepted in society, while only 36 percent of evangelical Protestants, 36 percent of Mormons and 16 percent of Jehovah’s Witnesses agreed.

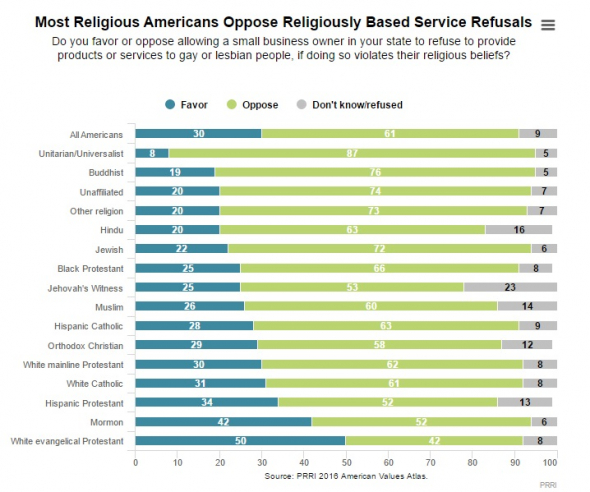

As reports have indicated in the last week that President Donald Trump is considering a possible “religious freedom order” that conservative religious freedom advocates say could do many things to protect the rights of religious institutions and federal contractors to operate their organizations in accordance with their beliefs, the PRRI data also shows that most American religious demographics oppose allowing businesses to refuse services for same-sex wedding ceremonies based on religious objections.

In recent years, small business owners across the U.S. were fined, sued and punished over their refusal to provide services for same-sex weddings because their participation would violate their religious beliefs. Advocates have called for state governments to give these religious business owners accommodations to non-discrimination laws, while opponents claim such exemptions would give these businesses a license to discriminate.

Complete Article HERE!

Complete Article HERE!

Happy New Year 2017

We made it!

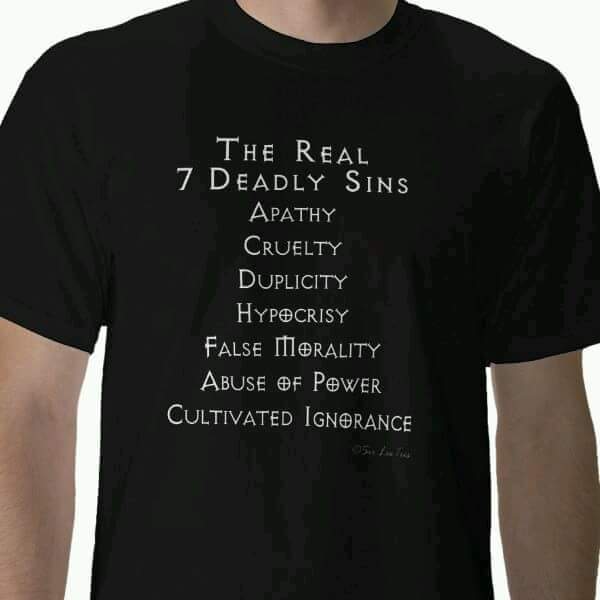

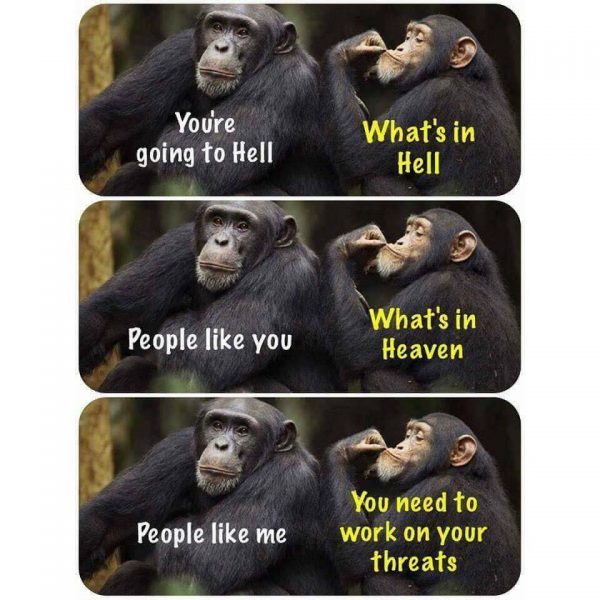

You’re going to hell!

Self-righteous people write to me all the time to tell me this. And my response is always the same.

Common Declaration by Pope Francis and Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby

Statement issued as 19 pairs of Anglican, Roman Catholic bishops sent out on mission

Pope Francis and Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby have said that they are “undeterred” by the “serious obstacles” to full unity between Anglicans and Roman Catholics.

In a Common Declaration, issued in Rome Oct. 5, the two say that the differences “cannot prevent us from recognizing one another as brothers and sisters in Christ by reason of our common baptism. Nor should they ever hold us back from discovering and rejoicing in the deep Christian faith and holiness we find within each other’s traditions.”

The Common Declaration was made at a service of Vespers in the Church of Saint Gregory on the Caelian Hill in Rome, from where, in 595AD, Pope Gregory sent Augustine to evangelise the Anglo-Saxon people. Augustine became the first archbishop of Canterbury in 597.

During the service, 19 pairs of Anglican and Roman Catholic bishops from across the world were commissioned by the pope and the archbishop before being “sent out” in mission together. Among the 19 pairings are Episcopal Bishop of Tennessee John Bauerschmidt and Roman Catholic Auxiliary Bishop of Baltimore Dennis Madden.

Pope Francis told them: “Fourteen centuries ago Pope Gregory sent the servant of God, Augustine, first Archbishop of Canterbury, and his companions, from this holy place, to preach the joyful message of the Word of God. Today we send you, dear brothers, servants of God, with this same joyful message of his everlasting kingdom.”

And Welby said: “Our Savior commissioned his disciples saying, ‘Peace be with you’. We too, send you out with his peace, a peace only he can give. May his peace bring freedom to those who are captive and oppressed, and may his peace bind into greater unity the people he has chosen as his own.”

Common Declaration

of HIS HOLINESS Pope Francis

and HIS GRACE Justin Welby ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY

Fifty years ago our predecessors, Pope Paul VI and Archbishop Michael Ramsey met in this city hallowed by the ministry and blood of the Apostles Peter and Paul. Subsequently, Pope John Paul II with Archbishop Robert Runcie, and later with Archbishop George Carey, and Pope Benedict XVI with Archbishop Rowan Williams, prayed together here in this Church of Saint Gregory on the Caelian Hill from where Pope Gregory sent Augustine to evangelise the Anglo-Saxon people. On pilgrimage to the tombs of these apostles and holy forebears, Catholics and Anglicans recognize that we are heirs of the treasure of the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the call to share that treasure with the whole world. We have received the Good News of Jesus Christ through the holy lives of men and women who preached the Gospel in word and deed and we have been commissioned, and empowered by the Holy Spirit, to be Christ’s witnesses “to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1: 8). We are united in the conviction that “the ends of the earth” today, is not only a geographical term, but a summons to take the saving message of the Gospel particularly to those on the margins and the peripheries of our societies.

In their historic meeting in 1966, Pope Paul VI and Archbishop Ramsey established the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission to pursue a serious theological dialogue which, “founded on the Gospels and on the ancient common traditions, may lead to that unity in truth, for which Christ prayed”. Fifty years later we give thanks for the achievements of the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission, which has examined historically divisive doctrines from a fresh perspective of mutual respect and charity. Today we give thanks in particular for the documents of ARCIC II which will be appraised by us, and we await the findings of ARCIC III as it navigates new contexts and new challenges to our unity.

Fifty years ago our predecessors recognized the “serious obstacles” that stood in the way of a restoration of complete faith and sacramental life between us. Nevertheless, they set out undeterred, not knowing what steps could be taken along the way, but in fidelity to the Lord’s prayer that his disciples be one. Much progress has been made concerning many areas that have kept us apart. Yet new circumstances have presented new disagreements among us, particularly regarding the ordination of women and more recent questions regarding human sexuality. Behind these differences lies a perennial question about how authority is exercised in the Christian community. These are today some of the concerns that constitute serious obstacles to our full unity. While, like our predecessors, we ourselves do not yet see solutions to the obstacles before us, we are undeterred. In our trust and joy in the Holy Spirit we are confident that dialogue and engagement with one another will deepen our understanding and help us to discern the mind of Christ for his Church. We trust in God’s grace and providence, knowing that the Holy Spirit will open new doors and lead us into all truth (cf. John 16: 13).

These differences we have named cannot prevent us from recognizing one another as brothers and sisters in Christ by reason of our common baptism. Nor should they ever hold us back from discovering and rejoicing in the deep Christian faith and holiness we find within each other’s traditions. These differences must not lead to a lessening of our ecumenical endeavours. Christ’s prayer at the Last Supper that all might be one (cf. John 17: 20-23) is as imperative for his disciples today as it was at that moment of his impending passion, death and resurrection, and consequent birth of his Church. Nor should our differences come in the way of our common prayer: not only can we pray together, we must pray together, giving voice to our shared faith and joy in the Gospel of Christ, the ancient Creeds, and the power of God’s love, made present in the Holy Spirit, to overcome all sin and division. And so, with our predecessors, we urge our clergy and faithful not to neglect or undervalue that certain yet imperfect communion that we already share.

Wider and deeper than our differences are the faith that we share and our common joy in the Gospel. Christ prayed that his disciples may all be one, “so that the world might believe” (John 17: 21). The longing for unity that we express in this Common Declaration is closely tied to the desire we share that men and women come to believe that God sent his Son, Jesus, into the world to save the world from the evil that oppresses and diminishes the entire creation. Jesus gave his life in love, and rising from the dead overcame even death itself. Christians who have come to this faith, have encountered Jesus and the victory of his love in their own lives, and are impelled to share the joy of this Good News with others. Our ability to come together in praise and prayer to God and witness to the world rests on the confidence that we share a common faith and a substantial measure of agreement in faith.

The world must see us witnessing to this common faith in Jesus by acting together. We can, and must, work together to protect and preserve our common home: living, teaching and acting in ways that favour a speedy end to the environmental destruction that offends the Creator and degrades his creatures, and building individual and collective patterns of behaviour that foster a sustainable and integral development for the good of all. We can, and must, be united in a common cause to uphold and defend the dignity of all people. The human person is demeaned by personal and societal sin. In a culture of indifference, walls of estrangement isolate us from others, their struggles and their suffering, which also many of our brothers and sisters in Christ today endure. In a culture of waste, the lives of the most vulnerable in society are often marginalised and discarded. In a culture of hate we see unspeakable acts of violence, often justified by a distorted understanding of religious belief. Our Christian faith leads us to recognise the inestimable worth of every human life, and to honour it in acts of mercy by bringing education, healthcare, food, clean water and shelter and always seeking to resolve conflict and build peace. As disciples of Christ we hold human persons to be sacred, and as apostles of Christ we must be their advocates.

Fifty years ago Pope Paul VI and Archbishop Ramsey took as their inspiration the words of the apostle: “Forgetting those things which are behind, and reaching forth unto those things which are before, I press towards the mark for the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 3: 13-14). Today, “those things which are behind” – the painful centuries of separation –have been partially healed by fifty years of friendship. We give thanks for the fifty years of the Anglican Centre in Rome dedicated to being a place of encounter and friendship. We have become partners and companions on our pilgrim journey, facing the same difficulties, and strengthening each other by learning to value the gifts which God has given to the other, and to receive them as our own in humility and gratitude.

We are impatient for progress that we might be fully united in proclaiming, in word and deed, the saving and healing gospel of Christ to all people. For this reason we take great encouragement from the meeting during these days of so many Catholic and Anglican bishops of the International Anglican-Roman Catholic Commission for Unity and Mission (IARCCUM) who, on the basis of all that they have in common, which generations of ARCIC scholars have painstakingly unveiled, are eager to go forward in collaborative mission and witness to the “ends of the earth”. Today we rejoice to commission them and send them forth in pairs as the Lord sent out the seventy-two disciples. Let their ecumenical mission to those on the margins of society be a witness to all of us, and let the message go out from this holy place, as the Good News was sent out so many centuries ago, that Catholics and Anglicans will work together to give voice to our common faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, to bring relief to the suffering, to bring peace where there is conflict, to bring dignity where it is denied and trampled upon.

In this Church of Saint Gregory the Great, we earnestly invoke the blessings of the Most Holy Trinity on the continuing work of ARCIC and IARCCUM, and on all those who pray for and contribute to the restoration of unity between us.

Rome, 5 October 2016

HIS GRACE JUSTIN WELBY HIS HOLINESS FRANCIS

Complete Article HERE!

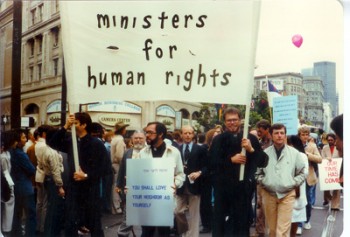

40 years ago today!

This happened.

Well that didn’t turn out like I hoped or imagined it would.

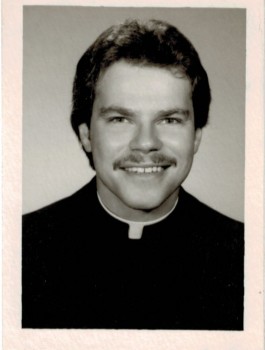

I wanted to be a priest ever since I was a little boy and I overcame the greatest of odds to achieve my life’s goal. On Saturday, November 22, 1975, I was ordained a Catholic Priest at the Cathedral of Saint Francis de Sales in Oakland, CA.

Sadly, it all came crashing to a halt only 6 years later with the publication of my doctoral dissertation.

The Oblates of Mary Immaculate, my religious community at the time, assigned me to post graduate studies in San Francisco in 1978. I completed that assignment in January 1981 with my dissertation, Gay Catholic Priests; A Study of Cognitive and Affective Dissonance. A media firestorm erupted shortly there after when I publicly identified myself as gay. (I had come out to my provincial superiors before I was ordained six years earlier.)

When word got to Rome, however, the Oblates began a process to dismiss me from the community. They erroneously accused me of “living a false lifestyle” because of my public declaration a month earlier. The community leadership claimed that anyone who would self identify as gay must also be sexually active. In their defense, it was 1981, and I had just studied a population of gay priests in the active ministry, years and years before the Church could even bring itself to admit that there were such a thing as gay priests in their midst. Nonetheless, my efforts to explain myself and the nature of self-identification fell on deaf ears. I was to be made an example of how others would be treated if they came out.

Priesthood was my whole life. To be cut off from the community and ministry in an instant, without due process nearly killed me. And thus, began a grueling 13-year battle with the Church to save my good name, my priesthood, and my ministry. I chronicled this odyssey in a book published in 2011, Secrecy, Sophistry And Gay Sex In The Catholic Church.

I lost the battle in 1994; I was dismissed from the Oblates. But I believe I won the war.

I lost the battle in 1994; I was dismissed from the Oblates. But I believe I won the war.

Martin Luther King, Jr once said, “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” Looking back on the last 40 years, I can see clearly that Dr King was right. LGBT people have gone from pariah status to having their relationships granted the same legal and societal status as straight people. Acceptance of LGBT people is at an all-time high in this country and throughout most of the world. And young U.S. Catholics overwhelmingly accept LGBT people.

Unfortunately, Church leadership continues to drag it’s feet. While there are some enlightened bishops, and certainly the Pope is pointing the way, most of the other church leadership have their head in the sand. The rear-guard action of trying to defend the indefensible continues unabated. Gay priests are still persecuted for coming out and the clerical closet continues to make Catholic priest sick, sometimes even to death, One has to ask; how can anyone preach the Good News while living a lie?

Forty years after ordination, I believe that I now know the real meaning of priesthood and ministry. And I can safely say that it has nothing to do with the ritual depicted in the photos above. My priesthood and ministry are rooted in knowing who I am and knowing that God called me as I am. My priesthood is to the people on the margins and the sexual fringe. And my priesthood means speaking truth to power and supporting others to do the same. I continue to stand against the fear, ignorance, and repression that destroys God’s people. And if I have to do my priesthood standing this distance from the altar, then I’m ok with that.