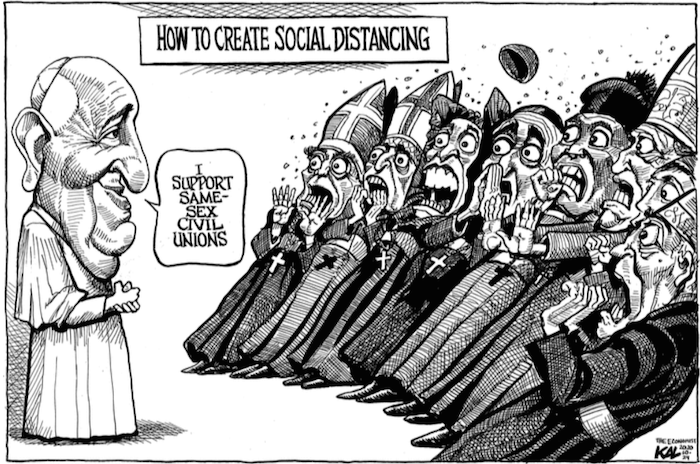

Now look what you’ve gone and done, Francis!

Alliance, Support & Activism

Belief in the virgin birth comes from the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Their birth stories are different, but both present Mary as a virgin when she became pregnant with Jesus. Mary and Joseph begin their sexual relationship following Jesus’ birth, and so Jesus has brothers and sisters.

Catholic piety goes beyond this, with Mary depicted as a virgin not only before but also during and after Jesus’ birth, her hymen miraculously restored. The brothers and sisters of Jesus are seen as either cousins or children of Joseph by an earlier marriage.

In Catholicism, Mary remains a virgin throughout her married life. This view arises not from the New Testament but from an apocryphal Gospel in the second century, the “Protoevangelium of James”, which affirms Mary’s perpetual virginity.

From the second century onwards, Christians saw virginity as an ideal, an alternative to marriage and children. Mary was seen to exemplify this choice, along with Jesus and the apostle Paul. It accorded with the surrounding culture where Greek philosophers, male and female, tried to live a simple life without attachment to family or possessions.

This extolling of virginity, however unlikely when applied to Mary, did have some advantages. The option of becoming a celibate nun in community with other women gave young women in the early church an attractive alternative to marriage, in a culture where marriages were generally arranged and death in childbirth was common.

Yet belief in the eternal virginity of Mary has also inflicted damage over the centuries, particularly on women. It has distorted the character of Mary, turning her into a submissive, dependent creature, without threat to patriarchal structures.

She is divorced from the lives of real women who can never attain her sexless motherhood or her unsullied “purity”.

Yet in the Gospels, Mary is a vibrant figure: strong-minded and courageous, a leader in the community of faith.

Simone de Beauvoir, the influential, early French feminist, observed that the cult of the Virgin Mary represented the “supreme victory of masculinity”, implying that it served the interests of men rather than women.

The ever-Virgin diminishes women’s sexuality and makes the female body and female sexuality seem unwholesome, impure. She is a safe and nonthreatening figure for celibate men who place her on a pedestal, both literally and metaphorically.

It is true that Catholic women across the world have found great solace in the compassionate figure of Mary, especially against images of a very masculine, judgmental God, and the brutality of political and religious hierarchy.

But for this women have paid a price, in their exclusion from leadership. Mary’s voice has been permitted, in filtered tones, to ring out across the church, but real women’s voices are silent.

In today’s context, the cult of the Virgin becomes emblematic of the way the church silences women and marginalises their experience.

Marian piety in its traditional form has a deep contradiction at its heart. In a speech in 2014, Pope Francis said, “The model of maternity for the Church is the Virgin Mary” who “in the fullness of time conceived through the Holy Spirit and gave birth to the Son of God.”

If that were true, women could be ordained, since their connection to Mary would allow them, like her, to represent the church. If the world received the body of Christ from this woman, Mary, then women today should not be excluded from giving the body of Christ, as priests, to the faithful at Mass.

The Virgin cult cuts women off from the full, human reality of Mary, and so from full participation in the life of the church.

It is no coincidence that in the early 20th century, the Vatican forbade Mary to be depicted in priestly vestments. She could only ever be presented as the unattainable virgin-mother: never as leader, and never as a fully embodied woman in her own right.

The irony of this should not be lost. A fully human Gospel symbol of female authority, autonomy, and the capacity to envision a transformed world becomes a tool of patriarchy.

By contrast, the Mary of the Gospels, the God-bearer and priestly figure – a normal wife and mother of children – confirms women in their embodied humanity and supports their efforts to challenge unjust structures, both within and outside the church.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By Josh Milton

As the Catholic Church prepares for its contended review, the Commission for Marriage and Family of the German Bishops’ Conference came to the consensus that being gay is a “normal form of sexual predisposition.”

Moreover, church organisers committed to “newly assessing” topics such as sacraments of ordination and marriage, with another revision being that adultery will not longer “always be qualified as grave sin”, the Catholic News Agency reported.

For centuries, Church leaders have been rattled by the thought of people being sexualities other than heterosexual. But as public attitudes and governments overwhelmingly sway in favour of letting the LGBT+ community exist, the church has steadily caught up to speed.

The German Catholic Church’s statement comes ahead of a two-year ‘Synodal Process’ by the Germans which will see a national reform consultation. Although, Vatican leaders have warned against this.

In a press release detailing the conclusions of the conference, it detailed how a panel of bishops, sexologists, moral theologians and canon lawyers deliberated how to discuss “the sexuality of man […] scientifically-theologically, and how to assess it ecclesiastically.”

The experts, consisting of bishops from four diocese, agreed in the Berlin conference that “human sexuality encompasses a dimension of lust, of procreation, and of relationships”, the release stated.

“There was also agreement that the sexual preference of man expresses itself in puberty and assumes a hetero- or homosexual orientation. Both belong to the normal forms of sexual predisposition, which cannot or should be be changed with the help of a specific socialisation.”

The panel also said that “any form of discrimination of those persons with a homosexual orientation has to be rejected.”

However, the panel did not reach a consensus across all battle lines. There was no consensus on “whether the magisterial ban on practiced homosexuality is still up to date.”

Furthermore, the experts also disagreed on whether or not both married and unmarried people should be allowed to use artificial contraceptives.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Pope Francis has spoken openly about homosexuality. In a recent interview, the pope said that homosexual tendencies “are not a sin.” And a few years ago, in comments made during an in-flight interview, he said,

“If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?”

However, the pope has also discouraged homosexual men from entering the priesthood. He categorically stated in another interview that for one with homosexual tendencies, the “ministry or the consecrated life is not his place.”

Many gay priests, when interviewed by The New York Times, characterized themselves as being in a “cage” as a result of the church’s policies on homosexuality.

As a scholar specializing in the history of the Catholic Church and gender studies, I can attest that 1,000 years ago, gay priests were not so restricted. In earlier centuries, the Catholic Church paid little attention to homosexual activity among priests or laypeople.

While the church’s official stance prohibiting sexual relations between people of the same sex has remained constant, the importance the church ascribes to the “sin” has varied. Additionally, over centuries, the church only sporadically chose to investigate or enforce its prohibitions.

While the church’s official stance prohibiting sexual relations between people of the same sex has remained constant, the importance the church ascribes to the “sin” has varied. Additionally, over centuries, the church only sporadically chose to investigate or enforce its prohibitions.

Prior to the 12th century, it was possible for priests – even celebrated ones like the 12th-century abbot and spiritual writer St. Aelred of Riveaulx – to write openly about same-sex desire, and ongoing emotional and physical relationships with other men.

The Bible places as little emphasis on same-sex acts as the early church did, even though many Christians may have been taught that the Bible clearly prohibits homosexuality.

Judeo-Christian scriptures rarely mention same-sex sexuality. Of the 35,527 verses in the Catholic Bible, only seven – 0.02% – are sometimes interpreted as prohibiting homosexual acts.

Even within those, apparent references to same-sex relations were not originally written or understood as categorically indicting homosexual acts, as in modern times. Christians before the late 19th century had no concept of gay or straight identity.

For example, Genesis 19 records God’s destruction of two cities, Sodom and Gomorrah, by “sulphur and fire” for their wickedness. For 1,500 years after the writing of Genesis, no biblical writers equated this wickedness with same-sex acts. Only in the first century A.D. did a Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria, first mistakenly equate Sodom’s sin with same-sex sexuality.

It took centuries for a Christian consensus to agree with Philo’s misinterpretation, and it eventually became the accepted understanding of this scripture, from which the derogatory term “sodomite” emerged.

Today, however, theologians generally affirm that the wickedness God punished was the inhabitants’ arrogance and lack of charity and hospitality, not any sex act.

Religious scholars have similarly researched the other six scriptures that Christians in modern times claim justify God’s categorical condemnation of all same-sex acts. They have uncovered how similar mistranslations, miscontextualizations, and misinterpretations have altered the meanings of these ancient scriptures to legitimate modern social prejudices against homosexuality.

For example, instead of labeling all homosexual acts as sinful in the eyes of God, ancient Christians were concerned about excesses of behavior that might separate believers from God. The apostle Paul criticized same-sex acts along with a list of immoderate behaviors, such as gossip and boastfulness, that any believer could overindulge in.

He could not have been delivering a blanket condemnation of homosexuality or homosexuals because these concepts would not exist for 1,800 more years.

Early church leaders didn’t seem overly concerned about punishing those who engaged in homosexual practice. I have found that there is a remarkable silence about homosexual acts, both in theologies and in church laws for over 1,000 years, before the late 12th century.

When early Christian commentators such as John Chrysostom, one of the most prolific biblical writers of the fourth century, criticized homosexual acts, it was typically part of an ascetic condemnation of all sexual experiences.

Moreover, it was generally not the sex act itself that was sinful but some consequence, such as how participating in an act might violate social norms like gender hierarchies. Social norms dictated that men be dominant and women passive in most circumstances.

If a man took on the passive role in a same-sex act, he took on the woman’s role. He was “unmasculine and effeminate,” a transgression of the gender hierarchy that Philo of Alexandria called the “greatest of all evils.” The concern was to police gender roles rather than sex acts, in and of themselves.

Before the mid-12th century, the church grouped sodomy among many sins involving lust, but their penalties for same sex-relations were very lenient if they existed or were enforced at all.

Church councils and penance manuals show little concern over the issue. In the early 12th century, a time of church revival, reform and expansion, prominent priests and monks could write poetry and letters glorifying love and passion – even physical passion – toward those of the same sex and not be censured.

Instead, it was civil authorities that eventually took serious interest in prosecuting the offenders.

By the end of the 12th century, the earlier atmosphere of relative tolerance began to change. Governments and the Catholic Church were growing and consolidating greater authority. They increasingly sought to regulate the lives – even private lives – of their subjects.

The Third Lateran Council of 1179, a church council held at the Lateran palace in Rome, for example, outlawed sodomy. Clerics who practiced it were either to be defrocked or enter a monastery to perform penance. Laypeople were more harshly punished with excommunication.

It might be mentioned that such hostility grew, not only toward people  engaging in same-sex relations but toward other minority groups as well. Jews, Muslims and lepers also faced rising levels of persecution.

engaging in same-sex relations but toward other minority groups as well. Jews, Muslims and lepers also faced rising levels of persecution.

While church laws and punishments against same-sex acts grew increasingly harsh, they were, at first, only sporadically enforced. Influential churchmen, such as 13th-century theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas and popular preacher Bernardino of Siena, known as the “Apostle of Italy,” disagreed about the severity of sin involved.

By the 15th century, however, the church conformed to social opinions and became more vocal in condemning and prosecuting homosexual acts, a practice that continues to today.

Today, the Catholic Catechism teaches that desiring others of the same sex is not sinful but acting on those desires is.

As the Catechism says, persons with such desires should remain chaste and “must be accepted with respect and sensitivity. Every sign of unjust discrimination in their regard should be avoided.” Indeed, Catholic ministries such as DignityUSA and New Ways Ministries seek to serve and advocate for this population.

Yet gay priests are in a different category. They live and work under mandatory celibacy, often in same-sex religious orders. Pope Francis I has encouraged them to be “perfectly responsible” to avoid scandal, while discouraging other gay men from entering the priesthood.

Many fear retribution if they cannot live up to this ideal. For the estimated 30-40% of U.S priests who are gay, the openness of same-sex desire among clerics of the past is but a memory.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By Frank Bruni

Pat Fitzgerald, 67, has long loved being a Catholic, and the part he loved maybe most of all, for the past quarter-century, was his role as a spiritual mentor at retreats for students at a church-affiliated high school in Indianapolis, where he lives.

But he has been told that he’s not wanted anymore. His crime? He publicly supported his daughter, a guidance counselor at the school, after its administrators moved to get rid of her because she’s married to a woman.

The school’s treatment of Shelly Fitzgerald, 45, was a big local story last summer that went national; she ended up on “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” in September. It was one of many examples of Catholic institutions deciding almost whimsically to exile longtime employees — not priests or nuns but coaches, teachers, counselors — who had long been known to be gay but were suddenly regarded as liabilities.

Maybe they had quietly married their partners, formalizing those relationships and inadvertently drawing attention to themselves. Maybe some homophobic parent or congregant had belatedly learned about them and lodged a complaint. That’s what happened to Shelly Fitzgerald, and her 14 years of fine work at Roncalli High School no longer mattered. Only her 2015 marriage to her longtime partner did. She was told that she could stay on if she dissolved the union. She said no thanks and was kicked off school grounds in August.

The aftershocks still complicate the lives — and faith — of people around her: her students, their parents, her dad. On Facebook last month she posted a letter from him to the Roncalli community in which he explained that he’d just been disinvited from future retreats but thanked everyone for being such supportive friends over the years.

“Today my heart is broken,” he wrote, adding that the retreats he’d participated in — more than 40 in all — were “the most beautiful and holy settings I have ever witnessed.” He alluded only vaguely to his daughter’s case. “To people on both sides of this ongoing issue,” he wrote, “I hope you can find peace.”

But there’s no peace for the Catholic Church here. It’s too mired in its own hypocrisy. The tension between its official teaching and unofficial practice — between the ignorance of the past and the illumination of the present — grows tauter all the time.

Most Catholics support same-sex marriage, in defiance of the church’s formal position, and many parishes fully welcome L.G.B.T. people. Yet there are places, and times, when the hammer comes down.

Church leaders know full well that the priesthood would be decimated if closeted gay men were exposed and expelled. Yet the church as a matter of policy bars men with “deep-seated homosexual tendencies” and considers gay people “objectively disordered.”

Catholics are supposed to show compassion. Yet Shelly and her dad were shown anything but.

She has been on administrative leave since August, and last month her lawyer, David Page, filed a charge of discrimination against the school and the Archdiocese of Indianapolis with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. It has up to 180 days to respond.

On Tuesday morning he showed me paperwork for a second charge of discrimination that he said he would be filing imminently; it cites what happened to her father as an unlawful act of retaliation meant to dissuade Shelly from pressing her case.

Pat Fitzgerald, uncomfortable with media attention, declined to speak with me, preferring to let his daughter do the talking. “His struggle comes from caring about Roncalli and being in conflict with what they’ve done to me,” Shelly told me. In October he attended a protest against the church’s treatment of L.G.B.T. people. His sign said, “Please treat my daughter Shelly kindly.”

There is, by many accounts, profound anger and hurt at Roncalli. As it happens, Shelly was one of two directors of counseling there; the other, Lynn Starkey, 62, is in a same-sex civil union and in November filed her own charge of discrimination with the E.E.O.C., claiming a “hostile work environment” in the aftermath of Shelly’s departure. For now she remains on the job.

Many students started an L.G.B.T. advocacy group, Shelly’s Voice, that also attracted parents and other adults in the community. A related Facebook page, Time to Be a Rebel, has more than 4,500 members.

But one parent told me that students who question Shelly’s dismissal fear repercussions. “Seniors are being told that if they speak out, they take the chance of not being able to graduate,” the parent, who spoke with me on condition of anonymity, said.

Sign up for Frank Bruni’s newsletter

Get a more personal, less conventional take on political developments, newsmakers, cultural milestones and more with Frank Bruni’s exclusive commentary every week.

According to posts on the Facebook page, a small cluster of Roncalli students were invited last month to a lunch with Archbishop Charles C. Thompson of Indianapolis, only to have him stress that homosexuality is a disorder and its expression sinful. One student called it an ambush.

For comment on all of this, I contacted the Roncalli principal, who referred me to a spokesman for the archdiocese. The spokesman sent me a statement that said that Pat Fitzgerald’s exclusion from student retreats reflected the “continuing attention surrounding his daughter’s suspension” and “his own participation in public protests over Catholic Church teaching.” He was still welcome at Masses, the statement said.

In regard to Shelly’s suspension, a past statement from the archdiocese reiterated what the Catholic Church has said in similar cases: Employees of Catholic schools are expected to live in compliance with church teaching. But is that legally enforceable?

Shelly’s E.E.O.C. complaint tests where federal civil rights law covers sexual orientation, a matter on which courts in different areas of the country have disagreed. Also, the Catholic Church has attempted to claim a “ministerial exception” from nondiscrimination laws that conflict with religious tenets, but there’s continued dispute about whether this applies to workers, like Shelly, who aren’t in the clergy.

Shelly pointed out that the Catholic Church isn’t generally going after teachers who flout its rules by using birth control or divorcing or having sexual relations outside marriage. “They’re going after L.G.B.T. people,” she said. “They’re going to die on this hill.”

And they’re going to hurt people — like Shawn Aldrich, who attended Roncalli, just as his parents and his wife and her parents did. He has two children there now. What has happened to Shelly astounds him.

“She was phenomenal at her job,” Aldrich told me. “So why are we dismissing her?” He knows what church leaders say about homosexuality but noted, “It’s our church, too.” Besides, he said, “All of us are made in God’s image.”

He and his wife plan to end their family tradition. They won’t send their third child, now in seventh grade, to Roncalli. “And that breaks our hearts,” he said. “That absolutely breaks our hearts.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Recently, a Calgary woman filed two human rights complaints with the Alberta Human Rights Commission. The employee, Barb Hamilton, says she was pushed out the Calgary Catholic School District (CCSD) because of her sexuality and was refused employment on the grounds of marital status, religious belief and sexual orientation.

Hamilton says she knew of 10 LGBTQ students in the school where she was principal who had hurt themselves, including by cutting themselves or attempting suicide because of homophobia at home or school. She says she went to the district for help but nothing changed.

Many Canadians may believe that LGBTQ people are protected from discrimination. But my research into religiously inspired homophobia and transphobia in Canadian Catholic schools since 2004 shows there are other LGBTQ-identified teachers who suffer similar fates.

I personally experienced this risk when I taught high school English for CCSD.

It might seem strange that someone like me, a publicly “out” lesbian, sought employment with a Catholic school. But I was raised in a Catholic family that counts clergy among its members and I regarded myself as culturally Catholic. Having a Catholic background also made it easier for me to find a teaching position at a time when they were hard to get.

In the years that I taught for CCSD, I experienced homophobia daily. I knew I could no longer work for CCSD when a student where I was teaching died by suicide after suffering months of homophobic bullying because he was gay.

I left teaching to research homophobia and transphobia in Canadian Catholic schools and also to begin to question and understand how these phobias are institutionalized. In other words, who or what systems are responsible for creating and implementing homophobic and transphobic religious curriculum and administrative policies?

Using Catholic doctrine to fire LGBTQ teachers and to discriminate against queer students in Catholic schools violates Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the equality rights provision. Shouldn’t publicly funded Catholic schools respect the law?

Publicly funded Catholic schools currently have constitutional status in the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario. These separate schools are operated by civil authorities and are accountable to provincial governments. Religious bodies do not have a legal interest in them, and as such, Canadian Catholic separate schools are not private or parochial schools as is common in other countries.

Of course, the Charter also ensures freedom of conscience and religion. However, when the expression of particular religious beliefs calls for the suppression of another’s equality rights, freedoms are curtailed rather than safeguarded.

This recurring discrimination against sexual and gender minority groups could be due to the central contradiction within Catholic doctrine itself: the church’s teaching best summarized as “It’s OK to be gay, just don’t act on it,” — a position some Catholics reject.

An influential 2004 Ontario curricular and policy document, “Pastoral Guidelines to Assist Students of Same-Sex Orientation”, presents a variety of guidelines, personal stories and sections of the Catechism of the Catholic Church pertaining to homosexual attraction to convey a contradictory position. While homosexual acts are “intrinsically disordered,” people experiencing homosexual attraction are called to chastity and “must be accepted with respect, compassion, and sensitivity” and therefore are in need of “pastoral care.”

The pastoral guidelines document includes a statement on building safe communities and a 1986 letter to Canadian Bishops from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (a Vatican office). The letter elaborates on the official Church teachings, stating the “inclination of the homosexual person” is a “strong tendency ordered toward an intrinsic moral evil.” Many LGBTQ people refer to this document as the “Halloween Letter” because it is so scary and was issued October 1 (1986). The Assembly of Catholic Bishops of Ontario shares the resource, with this letter, on its website.

Where schools promote such contradictory messages associating respect and depravity with LGBTQ people, they have made Alberta and Ontario Catholic schools potential hotbeds for homophobia — places where dedicated teachers fear for their jobs, and where LGBTQ youth are denied true acceptance and as a consequence are at risk of bullying and depression among other things.

My recent book Homophobia in the Hallways: Heterosexism and Transphobia in Catholic Schools explores causes and effects of the long-standing disconnect between Canadian Catholic schools and the Canadian Charter of Human Rights vis-à-vis sexual and gender minority groups.

Charter rights regularly clash with Catholic doctrine about sexuality in schools as this doctrine is selectively interpreted and applied regarding how employees embody a “Catholic lifestyle,” as suggested in Catholic lifestyle teacher contracts.

I sought to document how such homophobic policies and views are impacting teachers and students and and to uncover what is actually happening.

Through interviews with 20 LGBTQ students and teachers in some Alberta and Ontario Catholic schools, and through media accounts, I found that publicly funded Catholic schools in Canada respond to non-heterosexual and non-binary gender students and teachers and in contradictory and inconsistent ways.

All of the research participants experienced some form of homophobia or transphobia in their Catholic schools. None described a Catholic school environment that accepted and welcomed sexual and gender diversity.

I documented the firing of lesbian and gay teachers because they married their same-sex partners; the firing of lesbian and gay teachers because they wanted to have children with their same-sex partners; the firing of transgender teachers for transitioning from one gender to another.

Something as simple as discussing holiday plans can reveal that a teacher who is a lesbian has a same-sex partner. If this detail is revealed to leaders, this teacher can be at risk of being deemed to be living contrary to Catholic teaching and therefore subject to punitive action.

The teachers are given very little, if any, warning and find themselves in meetings without the support of a union representative or lawyer.

I also documented how schools seek to prohibit students from attending their high school proms with their same-sex dates, bar students from appearing in gender-variant clothing for official school photographs or functions like the prom; and deny students the right to establish Gay–Straight Alliances.

I noted a similarity of experiences among research participants in the distant provinces of Alberta and Ontario, in terms of how they were subject to heteronormative repression where schools are legally accountable to provinces but look to Bishops for pastoral leadership.

Oppression is a problem not only for LGBTQ people and our allies, but for all of us concerned about human dignity, human rights, love for our neighbours and social justice.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By John Gehring

Several hundred Catholic bishops from around the country have gathered in Baltimore for a national meeting at a time when many of us faithful are grieving, angry and running out of patience. The horrifying scale of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, as chronicled by a Pennsylvania grand jury report in August that revealed widespread abuse and cover-up over several decades, underscores an obvious but essential point: Bishops can’t be trusted to police themselves.

Moreover, a recent investigation by The Boston Globe and The Philadelphia Inquirer found that more than 130 bishops — nearly one-third of those still living — have been accused of failing to adequately respond to sexual abuse in their dioceses. New explosions are still coming. Last month, a former assistant to Bishop Richard Malone of Buffalo released hundreds of secret documents that showed how the bishop continued to send predator priests back into parishes. Bishop Michael Bransfield of West Virginia resigned in September after claims that he had sexually harassed younger priests.

It’s not the first meeting of its kind: 16 years ago, after The Globe’s groundbreaking “Spotlight” investigation, bishops met in Dallas to adopt zero-tolerance policies. Any priest who had abused a minor would be removed. Civilian review boards would investigate claims of clergy misconduct. Those policies led to the removal of hundreds of priests, but the bishops didn’t implement procedures that held themselves to the same standard of accountability.

The Vatican, including Pope Francis, has also not done enough. A proposal to create a Vatican tribunal to evaluate accusations against bishops — an idea floated by the pope’s own Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors — has gone nowhere.

Marie Collins, an abuse survivor who resigned in frustration from the commission, rightly observed that “history will judge Pope Francis on his actions, not his intentions.”

The failure to hold bishops accountable perpetuates a privileged culture of clericalism that lets the hierarchy operate under different rules.

Bishops were scheduled to vote on policies to address the abuse crisis in Baltimore. But in a surprise move, Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, stunned his fellow bishops and media by announcing that the Vatican wanted those plans put on hold until after a February meeting in Rome called by Pope Francis that will bring together bishops from around the world. That could prove to be prudent for the final outcome, but it’s hard to overstate how tone deaf the timing is given the growing Catholic anger in the pews.

Whatever credibility the Catholic Church has left as a voice for justice in public life, the clock is ticking down fast.

Standards and systems that prioritize transparency and accountability are essential. But church leaders should also recognize that technical or bureaucratic responses are insufficient to address the urgency of this moment. The Catholic Church faces a profound crisis of legitimacy. This crisis is not only the product of sexual predation. Moving forward, Catholic leaders should be more open to at least discussing a host of thorny issues. The church’s patriarchal culture — most exemplified in excluding women from the priesthood — and its teachings about human sexuality and gender are rejected by not only many Americans but also a sizable share of faithful Catholics in the pews.

How does the church hope to influence the wider culture when pastors are ignored by many of its own flock?

At this dark crossroads for the Catholic Church, there is an opportunity for Pope Francis and the bishops to take a fresh look at the church and begin a prayerful discernment about the limits of patriarchy, human rights for L.G.B.T. people and the exclusion of women from the clergy. These will be uncomfortable but necessary topics to explore if the Catholic Church wants an era of renewal and its leaders hope to reclaim the ability to speak more persuasively to a diverse public square.

The final report from a recently concluded monthlong meeting at the Vatican that brought together young Catholics and hundreds of bishops from around the world acknowledged the need for a broader conversation about the church’s teachings on sexuality. There are questions, the report noted, “related to the body, to affectivity and to sexuality that require a deeper anthropological, theological, and pastoral exploration.” While conservative bishops such as Archbishop Charles Chaput of Philadelphia led the charge to make sure the descriptor “L.G.B.T.” was not included in a final report — a pre-synod working document used the term for the first time in Vatican history — that subtle but significant opening is an invitation for a long-overdue conversation.

Church teaching isn’t set by a poll or the shifting winds of popular opinion. At the same time, the church is not a static institution. Doctrine does change and develop. The Second Vatican Council met from 1962 until 1965, a time when bishops opened the windows of the church to the modern world. The council brought historic changes in the way Catholicism understood democracy, the Jewish faith, the role of lay Catholics, interfaith dialogue and liturgy.

The question isn’t whether the church should stay the same or change. Paradoxically, the church has always done both. The more essential question is whether a 2,000-year-old institution that thinks in centuries can once again stand with a foot firmly planted in the best of its tradition while stepping into the future renewed and relevant to a new generation.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The Vatican this month is showing unprecedented, if symbolic, outreach on issues of human sexuality, using for what’s believed to be the first time the term “LGBT” in a planning document for a huge upcoming bishops meeting. Vatican officials also invited to speak at a second global meeting a prominent advocate for LGBT people, something some gay Catholic groups say has never been done.

The two moves, announced in the past 10 days, are being seen by church-watchers as largely an effort to speak in a more respectful way with a younger generation of Catholics who are confronting the church on topics from female priests and abortion to sexuality — but who are clearly not ready to totally walk away from the faith.

The efforts related to the Synod of Bishops on Young People (in October) and the World Meeting of Families (in August) are part of an explicit push by Pope Francis’s church to say “we have to pay attention to this whole LGBT reality, especially for those who have chosen to remain in the church,” said the Rev. Thomas Rosica, who has often served as an English assistant to the Vatican press office.

On Tuesday, the Vatican released the details of the bishops’ synod, or meeting, the third in major global gatherings about the family. The others were in 2014 and 2015. While the document was released only in Italian, the National Catholic Reporter noted it was the first time the acronym was used. The Catholic Church “has in the past formally referred to gay people as ‘persons with homosexual tendencies,’ ” the Reporter said.

Rosica agreed it was a first, but said “they’re just using the lingo young people use. There’s nothing earth-shattering.” Vatican spokeswoman Paloma Garcia Ovejero declined to comment on the reason for the adoption of the acronym beyond saying, “I guess there’s no specific answer … it’s just the result of so many proposals and will be used as a ‘tool’ for discussion.”

Vatican spokesman Greg Burke did not respond to a request for comment.

Hundreds of bishops will attend the meeting in Rome to discuss how they can serve young people better. Their meeting will touch on topics from lack of job opportunities for young people in some places and migration to digital addiction and the struggle for reliable news.

In a section of the synod outline called “the body, affectivity and sexuality,” reports the Catholic Reporter, “It states: ‘Sociological studies demonstrate that many young Catholics do not follow the indications of the Church’s sexual moral teachings. … No bishops’ conference offers solutions or recipes, but many are of the point of view that questions of sexuality must be discussed more openly and without prejudice.’ ”

“There are young Catholics that find in the teachings of the Church a source of joy and desire ‘not only that they continue to be taught despite their unpopularity, but that they be proclaimed with greater depth,’ ” the Catholic Reporter quotes the document as saying. “Those that instead do not share the teachings express the desire to remain part of the Church and ask for a greater clarity about them.”

Francis DeBernardo, executive director of New Ways ministry, which aims to connect gay Catholics and their church, said the use of the term LGBT is very significant — especially compared with past language, such as people with “homosexual inclinations.”

“That said, there is nothing in this new document that indicates a change in church teaching. It simply indicates a new openness to discuss these issues more respectfully. How they actually conduct the synod, and, more importantly, what the final synod document will say, is much more important than these developments,” he wrote in an email to The Washington Post.

The second development involves the World Meeting of Families, a massive, Vatican-run event the Catholic Church holds once every three years. The last time it was held, in 2015, Francis was in Philadelphia. The church faced criticism from LGBT advocates when the only sign of gay families amid a days-long display of family issues was a gay man and his mother talking about celibacy.

Eight days ago, the Vatican announced details of the next World Meeting, Aug. 21 to 26 in Dublin. Among many other speakers will be the Rev. Jim Martin, a New York City Jesuit popularly known as Stephen Colbert’s pastor — but within the church as a fierce advocate for positive images and engagement with gay Catholics. Martin will be the first speaker at a World Meeting “on positive pastoral outreach to LGBT people,” the Associated Press reported“Building a Bridge,” about Catholic outreach to the LGBT community, has had several talks canceled in the United States in recent months because of pressure from conservative groups who oppose his call for the church to better accompany gay Catholics, the AP reported.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

A survivor of clerical sexual abuse has said Pope Francis told him that God had made him gay and loved him, in arguably the most strikingly accepting comments about homosexuality to be uttered by the leader of the Roman Catholic church.

Juan Carlos Cruz, who spoke privately with the pope two weeks ago about the abuse he suffered at the hands of one of Chile’s most notorious paedophiles, said the issue of his sexuality had arisen because some of the Latin American country’s bishops had sought to depict him as a pervert as they accused him of lying about the abuse.

“He told me, ‘Juan Carlos, that you are gay does not matter. God made you like this and loves you like this and I don’t care. The pope loves you like this. You have to be happy with who you are,’” Cruz told Spanish newspaper El País.

Now 87, Fernando Karadima, the man who abused Cruz, was found guilty of abuse by the Vatican in 2011.

Greg Burke, the Vatican’s chief spokesman, did not respond to questions about whether Cruz’s statement accurately reflected his conversation with the pope.

It is not the first time it has been suggested Francis has an open and tolerant attitude toward homosexuality, despite the Catholic church’s teaching that gay sex – and all sex outside of heterosexual marriage – is a sin. In July 2013, in response to a reporter’s question about the existence of an alleged “gay lobby” within the Vatican, Francis said: “Who am I to judge?”

The new remarks appear to go much further in embracing homosexuality as a sexual orientation that is designed and bestowed by God. It suggests that Francis does not believe that individuals choose to be gay or lesbian, as some religious conservatives argue.

Austen Ivereigh, who has written a biography of the pope, said Francis had likely made similar comments in private in the past, when he served as a spiritual director to gay people in Buenos Aires, but that Cruz’s public discussion of his conversation with Francis represented the most “forceful” remarks on the subject since 2013.

It did not, however, represent a shift in church teaching, Ivereigh said, since the church had never formally made any pronouncements on why individuals were gay.

Christopher Lamb, the Vatican correspondent for the Tablet, said the comments were remarkable and a sign of a shift in attitudes taking place. “It goes beyond ‘who am I to judge?’ to ‘you are loved by God,’” said Lamb. “I don’t think he has changed church teaching but he’s demonstrating an affirmation of gay Catholics, something that has been missing over the years in Rome.”

The remarks come as several high profile members of the clergy have sought to publicly make inroads with gay Catholics, many of whom have felt shunned and unwelcome in the church and have been ostracised.

Father James Martin, a Jesuit priest in New York who has nearly 200,000 Twitter followers, has led the outreach effort and was chosen last month to serve as a consultor to the Vatican’s secretariat for communications.

Martin has argued in his book Building a Bridge that the onus is on the church to make LGBT Catholics feel welcome in the church and to stop discriminating against people based on their “sexual morality”.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!