In 1980, a gay historian’s book about Catholic Church-approved homosexuality enraged both gays and Catholics.

It might have been the first academic textbook that greeted the masses via the medium of Garry Trudeau’s comic Doonesbury. In a series of strips in June 1994, recently outed gay character Mark Slackmeyer attempts to pick up a fundamentalist Christian married man, and tells him that the church had, for a millennium, performed gay-marriage ceremonies. “Where did you hear such garbage?” the man replies, irate.

“It’s in a new book by this Yale professor,” answers Slackmeyer. “His research turned up liturgies for same-sex ceremonies that included communion, holy invocations and kissing to signify union. They were just like heterosexual ceremonies, except that straight weddings, being about property, were usually held outdoors. Gay rites, being about love, were held INSIDE the church!”

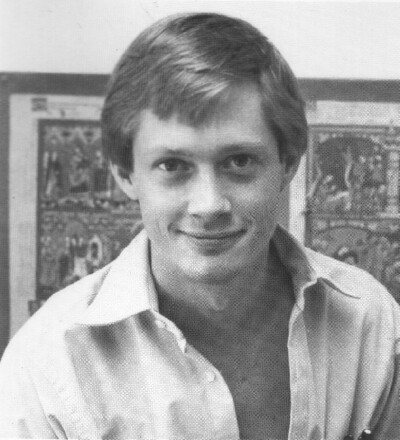

That week, at least two Illinois newspapers refused to print the strips, while a few dozen readers rang the distributor to ask “why Garry Trudeau exists to make their lives unhappy.” If the strip provoked controversy, the book, Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe, incited outrage both within and outside of the academic community. Its author, scholar John Eastburn Boswell, known as Jeb, died six months after the comic strips ran at the age of 47, of AIDS-related complications.

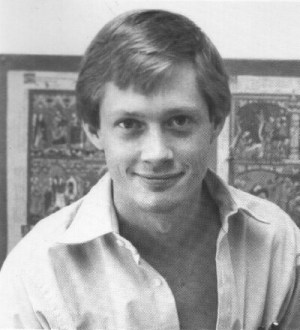

In barely 20 years at Yale, Boswell’s work as a historian managed to set the cat among the pigeons to stupendous effect, through years of meticulous scholarship that, if correct, undermined the very foundation of much modern homophobia. In the introduction to his 1980 American Book Award-winning Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century, he observed that gay people were “still the objects of severe proscriptive legislation, widespread public hostility, and various civil restraints, all with ostensibly religious justification.” Boswell’s work suggested, however, that this “religious justification” might, in fact, be bogus—a latter-day alteration, introduced hundreds of years after Christianity was founded.

The book argued that the Roman Catholic Church had not always been as hostile to gay people, and indeed, until the 12th century, had thought homosexuality no more troubling than, say, hypocrisy—or even celebrated love between men. The response to the book was explosive, if polarized. “I would not hesitate to call his book revolutionary,” Paul Robinson, a Stanford University historian, wrote in the New York Times Book Review in 1981. But other critics felt that, despite its attention to detail, its central thesis—that Christianity and homosexuality had not always been such uneasy bedfellows—was not only false, but a failed attempt by Boswell, gay and Catholic, to square two aspects of his identity they felt could not be reconciled.

Boswell was young and brilliant, blond and boyishly handsome, with an incredible facility for languages. His work might at any time draw on any of 17 dead and living examples—among them, Catalan, Latin, Old Iceland, Syriac and Persian. As a teenager growing up in Virginia, writes the researcher Bruce O’Brien, he had converted to Catholicism from Episcopalianism. This conversion was precipitated by a show of tolerance and strength: “because, in large part, the archdiocese of Baltimore had voluntarily desegregated its schools, without a court order, solely because it was the right thing to do.” Here, he saw a Catholic church that was intrinsically moral and would be a beacon of light against intolerance—one that might lead the charge on other struggles for equality in a country whose sensibilities were shifting at great pace.

Many saw the book, therefore, as a chance for a reckoning—Boswell giving the church the opportunity to welcome the gay community. As his sister Patricia, who spoke at his funeral, puts it: “Jeb’s love of God was the driving force in his life and the driving passion behind his work. He did not set out to shake up the straight world but rather to include the gay world in the love of Christ… to acquaint all with the fearsome power of that love, the wildness, the ‘not tameness’ of it.”

Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality is a 442-page journey through around 1,000 years of gay history. Assiduously researched, it jumps from country to country, instance to instance, drawing on examples of love between specific men, and generalized cases of societies in which sex between men was quite normalized.

Boswell spends some time delving into the relationship between the 4th-century Ausonius, a Roman poet living in Bordeaux, France, and his pupil Saint Paulinus, later the Bishop of Nola. Whether or not the relationship was a physical one is impossible to say—but the passionate affection the two had for one another seemed to transcend ordinary platonic friendship.

In whatever world I am found,

I shall hold you fast,

Grafted onto my being,

Not divided by distant shores or suns.

Everywhere you shall be with me,

I will see with my heart

And embrace you with my loving spirit.

“It would be inaccurate to suggest any exact parallel between such relationships and modern phenomena—as it is to compare medieval marriage with its modern counterpart,” Boswell wrote. But the idea that the concept of friendship has simply changed rang hollow to him—especially given that in many ancient societies, homosexuality was conventional and so might well have been part of a normal friendship. “Friends of the same sex borrowed from the standard vocabulary of homosexual love to express their feelings in erotic terms,” he wrote.

Saint Augustine, writing at the same time, described a friendship thus: “I felt that my soul and his were one soul in two bodies, and therefore life was a horror to me, since I did not want to live as a half; and yet I was also afraid to die lest he, whom I had loved so much, would completely die.” Elsewhere, however, he claims to have “contaminated the spring of friendship with the dirt of lust and darkened its brightness with the blackness of desire”—yet this is a denigration not specifically of homosexual lust and desire, but of sexuality more generally.

In the same period in Antioch, an ancient Greco-Roman city sometimes called “the cradle of Christianity,” Boswell described how Saint John Chrysostom visited the town, in what is today Turkey. Chrysostom was surprised to see the men of the city “consorting” not with prostitutes, but “fearlessly” with one another. Boswell quoted him: “The fathers of the young men take this in silence: they do not try to sequester their sons, nor do they seek any remedy for this evil. None is ashamed, no one blushes, but, rather, they take pride in their little game; the chaste seem to be the odd ones, and the disapproving the ones in error.” In this early Christian city, Chrysostom found homosexuality to be so very common and accepted that “there is some danger that womankind will become unnecessary with the future, with young men instead fulfilling all the needs women used to.”

Boswell shored up example after example of homosexual love and sex in the early Christian world over the course of almost 1,000 years. There were occasional laws against them, he pointed out, but they were not usually religious ones, but civil, where homosexual acts were fined as a way to increase tax coffers. Indeed, often the people being taxed in this way were not ordinary members of society, but bishops and clerics. “Purely ecclesiastical records usually stipulate either no penalty at all or a very mild one,” he wrote. Under Pope Saint Gregory II, for instance, lesbian activities carried a 160-day fasting penalty, likely under the same terms as Lent. A priest caught going hunting, on the other hand, would be in comparable trouble for three years.

In the 1980s, at a time when laws against sodomy remained in place in many American states, the book was a bombshell—especially for Catholics. The United States, at that time, was still a place of extreme homophobia and prejudice. In 1978, the openly gay politician Harvey Milk had been assassinated in San Francisco; a year earlier came Anita Bryant’s organized opposition to gay rights, with its rhetoric about saving children from gay “recruitment.” Queer studies remained a very niche part of academic study—Yale’s Lesbian and Gay Studies Center, which Boswell helped to found, emerged only in the late 1980s.

Criticism of Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, therefore, came on a variety of fronts. In some parts of the academic community, it came from historians like the R. W. Southern of the University of Oxford, who believed that “gay history” was not an interesting or important part of historical research. (Southern, O’Brien notes, was largely influenced by having grown up in “a repressed age where homosexuals were criminals [a word he used when talking about homosexuality.]”) In others, it came from theological scholars who picked apart Boswell’s thesis and found it undermined by the scholar’s deep, deep desire to be right. In the Catholic magazine Commonweal, after the book’s release, Louis Crompton wrote: “It is a pity that [the book] is … vitiated by a determination to construe all its voluminous evidence in the light of an untenable leading idea.” Some of its harshest criticism came from members of the gay community, who accused Boswell of being an apologist for the church’s atrocities against gay people. In the Gay Books Bulletin, Wayne Dyne wrote, decisively: “Christianity is definitely guilty of the stigmatization and persecution of same-sex relations in our civilization. It has served as a redoubt for bigotry of all sorts, and until those who call themselves Christians are ready humbly to acknowledge this, they are coming to us with dirty hands.”

Boswell, for his part, seemed to take the response in his stride. To the many critics who argued that such categories as “gay” and “straight” were modern conceptions, Boswell responded: “If the categories ‘homosexual/heterosexual’ and ‘gay/straight’ are the inventions of particular societies rather than real aspects of the human psyche, there is no gay history.” The book had caused controversy, but it had also won multiple awards and cleared important ground in developing this largely uncharted territory of gay studies.

Today, Boswell is remembered for two things—by those who didn’t know him, for his contributions to his field; and by those who did, for his unwavering kindness and generosity. A 1986 video of Boswell giving a talk shows a man who was at once dazzlingly bright and brilliantly charismatic. He’s likeable, urbane, often very funny. On and off campus, he was adored—by undergraduates, who clamored to be in his classes, and undergraduates; gay and straight members of faculty alike; and by many members of the Catholic community. At Harvard, where he had completed his PhD, he counted among his devoted friends John Spencer, rector of the Jesuit community of Boston, and Peter J. Gomes, the Plummer professor of Christian morals, after he came out publicly in 1991. “At a time of great public trauma for me, he wrote me out of the blue a lovely letter of support,” Gomes told the Harvard Crimson, shortly after Boswell’s death. “He gave me courage.”

When he passed away in December 1994, Boswell had been in the Yale infirmary for some months. The music historian Geoffrey Block recalled visiting him in his hospital room, where, despite having only recently emerged from a coma, he was “brilliantly and miraculously holding court,” quoting lines from films and singing “Cause I’m a Blonde” from the musical Earth Girls Are Easy. Admirers and friends drifted in and out of the infirmary—friends he had helped through crises; a devoted graduate student; his father; the newly installed President of Yale, Richard Levin, who cried freely and readily. “A young barber who came to the infirmary room to give Jeb a haircut moved us to tears when he refused payment.”

Boswell died on Christmas Eve, surrounded by family, friends, and his partner of many years, Jerry Hart. In the months leading up to his death, Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe, which had been previewed in Doonesbury, incited similar levels of controversy to Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Comprised of the study of more than 60 manuscripts from the 8th to the 16th century, it was a full investigation into the history of same-sex unions. These he described as relationships that were “unmistakably a voluntary, emotional union of two persons,” and “closely related” to heterosexual marriage, “no matter how much some readers may be discomforted by this.” Again, critics argued that he was looking for something that he dearly wanted to be there. Block, in his 2013 memorial, wrote how delighted and thrilled Boswell would have been to have been able to legally marry Hart. “I came across a sign on a lawn that would have made Jeb, a devout Catholic—perhaps paradoxically considering this institution’s take on his sexual identity—extremely happy. It simply said, ‘Approve R-74. My Church Supports Marriage Equality’.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

John Boswell (1947-1994) was a prominent scholar who researched and wrote about the importance of gays and lesbians in Christian history. He was born on March 20, 1947.

John Boswell (1947-1994) was a prominent scholar who researched and wrote about the importance of gays and lesbians in Christian history. He was born on March 20, 1947.

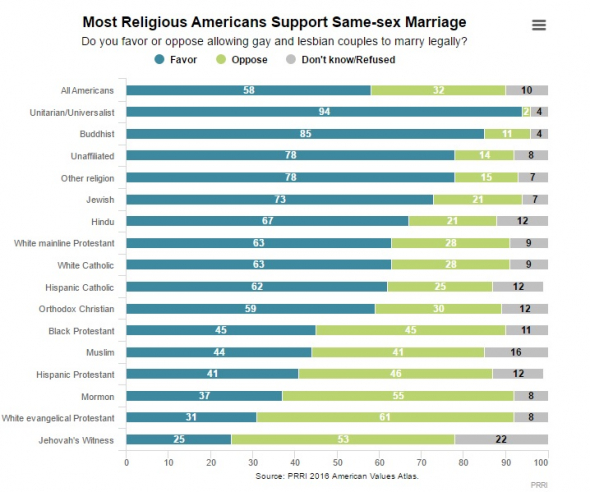

found that 54 percent of all Christians surveyed agreed that homosexuality should be accepted by society. Over half of all Roman Catholic, Mainline Protestant, Orthodox Christians and African-American Protestant respondents said they believe that homosexuality should be accepted in society, while only 36 percent of evangelical Protestants, 36 percent of Mormons and 16 percent of Jehovah’s Witnesses agreed.

found that 54 percent of all Christians surveyed agreed that homosexuality should be accepted by society. Over half of all Roman Catholic, Mainline Protestant, Orthodox Christians and African-American Protestant respondents said they believe that homosexuality should be accepted in society, while only 36 percent of evangelical Protestants, 36 percent of Mormons and 16 percent of Jehovah’s Witnesses agreed. Complete Article

Complete Article