Pope Francis has spoken openly about homosexuality. In a recent interview, the pope said that homosexual tendencies “are not a sin.” And a few years ago, in comments made during an in-flight interview, he said,

“If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?”

However, the pope has also discouraged homosexual men from entering the priesthood. He categorically stated in another interview that for one with homosexual tendencies, the “ministry or the consecrated life is not his place.”

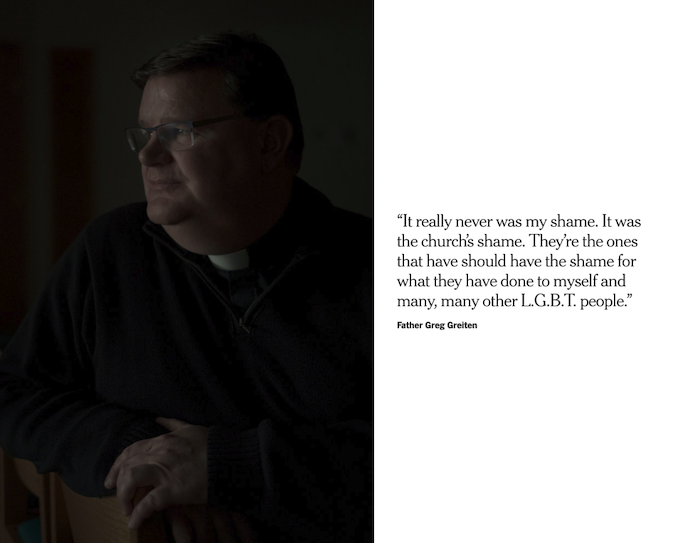

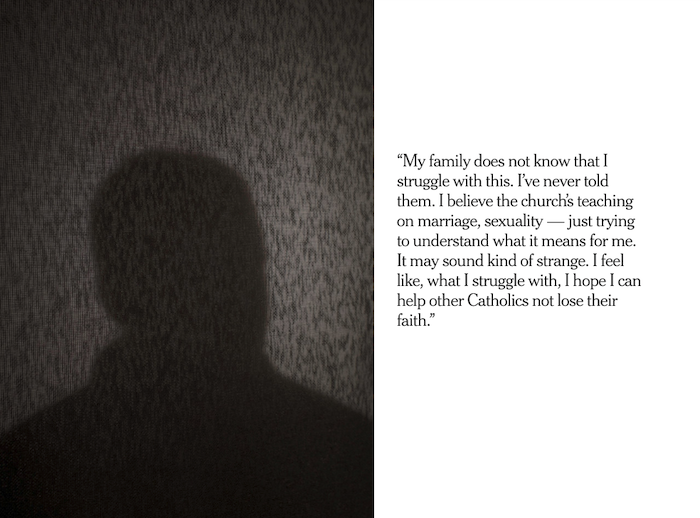

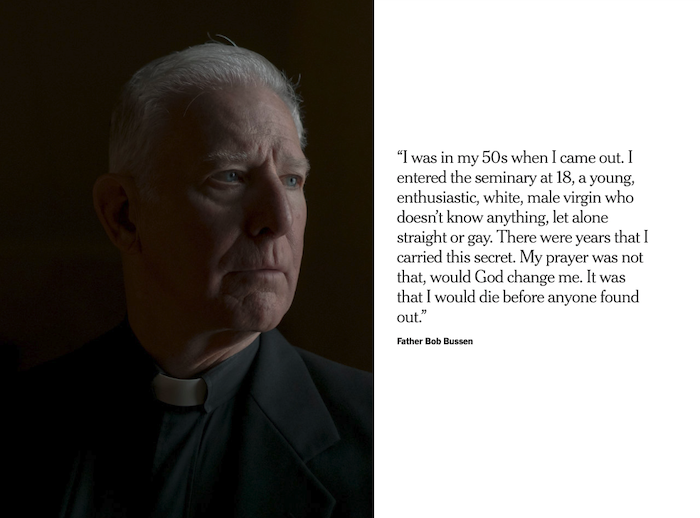

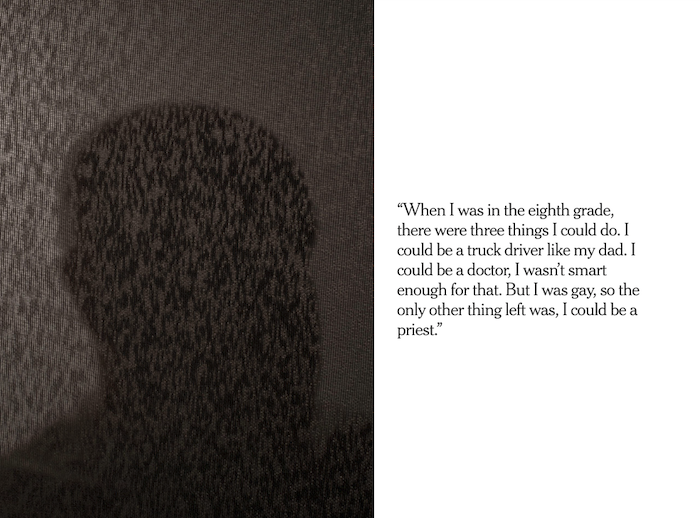

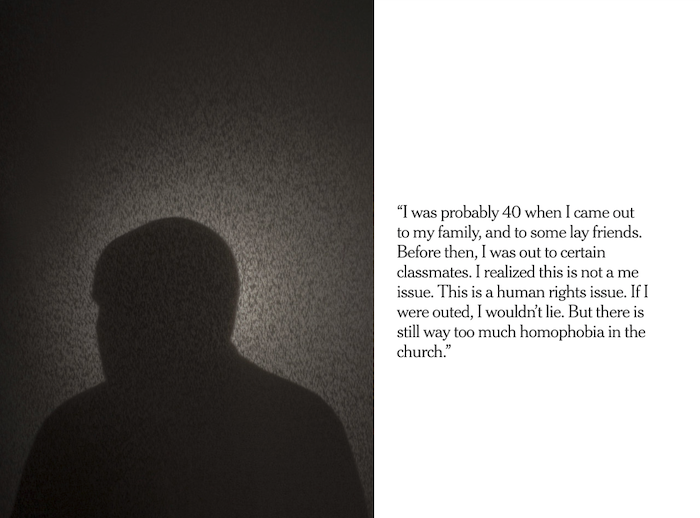

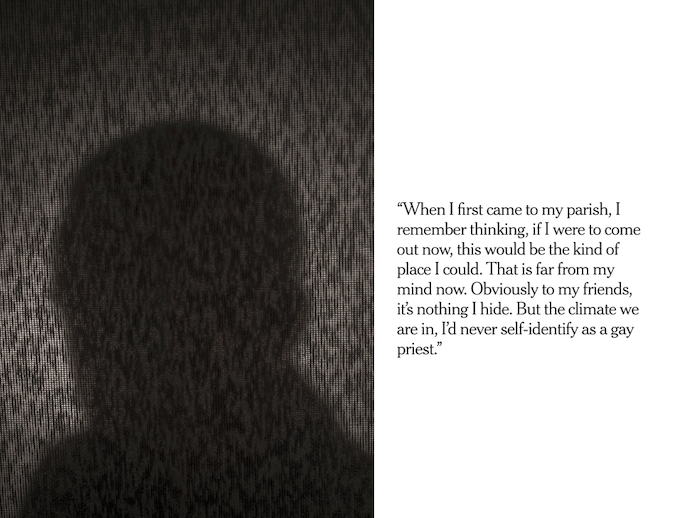

Many gay priests, when interviewed by The New York Times, characterized themselves as being in a “cage” as a result of the church’s policies on homosexuality.

As a scholar specializing in the history of the Catholic Church and gender studies, I can attest that 1,000 years ago, gay priests were not so restricted. In earlier centuries, the Catholic Church paid little attention to homosexual activity among priests or laypeople.

Open admission of same-sex desires

While the church’s official stance prohibiting sexual relations between people of the same sex has remained constant, the importance the church ascribes to the “sin” has varied. Additionally, over centuries, the church only sporadically chose to investigate or enforce its prohibitions.

While the church’s official stance prohibiting sexual relations between people of the same sex has remained constant, the importance the church ascribes to the “sin” has varied. Additionally, over centuries, the church only sporadically chose to investigate or enforce its prohibitions.

Prior to the 12th century, it was possible for priests – even celebrated ones like the 12th-century abbot and spiritual writer St. Aelred of Riveaulx – to write openly about same-sex desire, and ongoing emotional and physical relationships with other men.

Biblical misunderstandings

The Bible places as little emphasis on same-sex acts as the early church did, even though many Christians may have been taught that the Bible clearly prohibits homosexuality.

Judeo-Christian scriptures rarely mention same-sex sexuality. Of the 35,527 verses in the Catholic Bible, only seven – 0.02% – are sometimes interpreted as prohibiting homosexual acts.

Even within those, apparent references to same-sex relations were not originally written or understood as categorically indicting homosexual acts, as in modern times. Christians before the late 19th century had no concept of gay or straight identity.

For example, Genesis 19 records God’s destruction of two cities, Sodom and Gomorrah, by “sulphur and fire” for their wickedness. For 1,500 years after the writing of Genesis, no biblical writers equated this wickedness with same-sex acts. Only in the first century A.D. did a Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria, first mistakenly equate Sodom’s sin with same-sex sexuality.

It took centuries for a Christian consensus to agree with Philo’s misinterpretation, and it eventually became the accepted understanding of this scripture, from which the derogatory term “sodomite” emerged.

Today, however, theologians generally affirm that the wickedness God punished was the inhabitants’ arrogance and lack of charity and hospitality, not any sex act.

Religious scholars have similarly researched the other six scriptures that Christians in modern times claim justify God’s categorical condemnation of all same-sex acts. They have uncovered how similar mistranslations, miscontextualizations, and misinterpretations have altered the meanings of these ancient scriptures to legitimate modern social prejudices against homosexuality.

For example, instead of labeling all homosexual acts as sinful in the eyes of God, ancient Christians were concerned about excesses of behavior that might separate believers from God. The apostle Paul criticized same-sex acts along with a list of immoderate behaviors, such as gossip and boastfulness, that any believer could overindulge in.

He could not have been delivering a blanket condemnation of homosexuality or homosexuals because these concepts would not exist for 1,800 more years.

Gay sex, as such, usually went unpunished

Early church leaders didn’t seem overly concerned about punishing those who engaged in homosexual practice. I have found that there is a remarkable silence about homosexual acts, both in theologies and in church laws for over 1,000 years, before the late 12th century.

When early Christian commentators such as John Chrysostom, one of the most prolific biblical writers of the fourth century, criticized homosexual acts, it was typically part of an ascetic condemnation of all sexual experiences.

Moreover, it was generally not the sex act itself that was sinful but some consequence, such as how participating in an act might violate social norms like gender hierarchies. Social norms dictated that men be dominant and women passive in most circumstances.

If a man took on the passive role in a same-sex act, he took on the woman’s role. He was “unmasculine and effeminate,” a transgression of the gender hierarchy that Philo of Alexandria called the “greatest of all evils.” The concern was to police gender roles rather than sex acts, in and of themselves.

Before the mid-12th century, the church grouped sodomy among many sins involving lust, but their penalties for same sex-relations were very lenient if they existed or were enforced at all.

Church councils and penance manuals show little concern over the issue. In the early 12th century, a time of church revival, reform and expansion, prominent priests and monks could write poetry and letters glorifying love and passion – even physical passion – toward those of the same sex and not be censured.

Instead, it was civil authorities that eventually took serious interest in prosecuting the offenders.

The years of hostility

By the end of the 12th century, the earlier atmosphere of relative tolerance began to change. Governments and the Catholic Church were growing and consolidating greater authority. They increasingly sought to regulate the lives – even private lives – of their subjects.

The Third Lateran Council of 1179, a church council held at the Lateran palace in Rome, for example, outlawed sodomy. Clerics who practiced it were either to be defrocked or enter a monastery to perform penance. Laypeople were more harshly punished with excommunication.

It might be mentioned that such hostility grew, not only toward people  engaging in same-sex relations but toward other minority groups as well. Jews, Muslims and lepers also faced rising levels of persecution.

engaging in same-sex relations but toward other minority groups as well. Jews, Muslims and lepers also faced rising levels of persecution.

While church laws and punishments against same-sex acts grew increasingly harsh, they were, at first, only sporadically enforced. Influential churchmen, such as 13th-century theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas and popular preacher Bernardino of Siena, known as the “Apostle of Italy,” disagreed about the severity of sin involved.

By the 15th century, however, the church conformed to social opinions and became more vocal in condemning and prosecuting homosexual acts, a practice that continues to today.

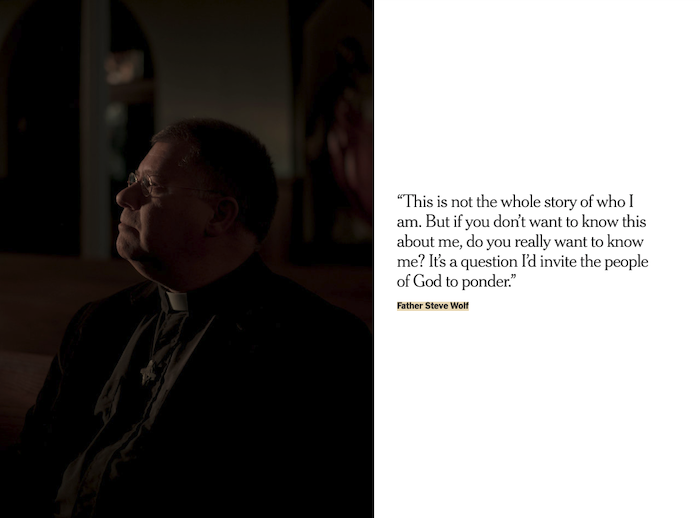

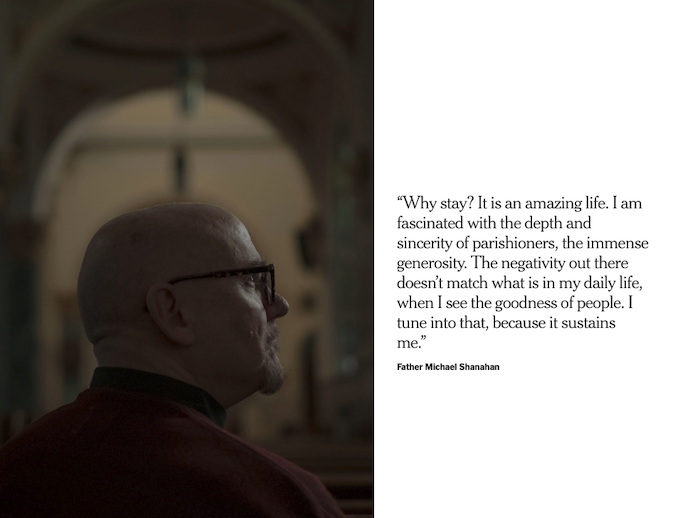

Priests fear retribution today

Today, the Catholic Catechism teaches that desiring others of the same sex is not sinful but acting on those desires is.

As the Catechism says, persons with such desires should remain chaste and “must be accepted with respect and sensitivity. Every sign of unjust discrimination in their regard should be avoided.” Indeed, Catholic ministries such as DignityUSA and New Ways Ministries seek to serve and advocate for this population.

Yet gay priests are in a different category. They live and work under mandatory celibacy, often in same-sex religious orders. Pope Francis I has encouraged them to be “perfectly responsible” to avoid scandal, while discouraging other gay men from entering the priesthood.

Many fear retribution if they cannot live up to this ideal. For the estimated 30-40% of U.S priests who are gay, the openness of same-sex desire among clerics of the past is but a memory.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!