Gay Catholic Priests Speak Out

The crisis over sexuality in the Catholic Church goes beyond abuse. It goes to the heart of the priesthood, into a closet that is trapping thousands of men.

By Elizabeth Dias

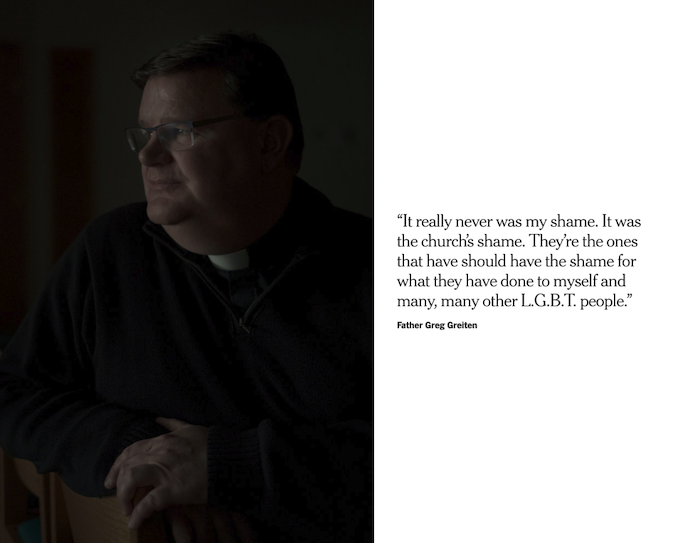

Gregory Greiten was 17 years old when the priests organized the game. It was 1982 and he was on a retreat with his classmates from St. Lawrence, a Roman Catholic seminary for teenage boys training to become priests. Leaders asked each boy to rank which he would rather be: burned over 90 percent of his body, paraplegic, or gay.

Each chose to be scorched or paralyzed. Not one uttered the word “gay.” They called the game the Game of Life.

The lesson stuck. Seven years later, he climbed up into his seminary dorm window and dangled one leg over the edge. “I really am gay,” Father Greiten, now a priest near Milwaukee, remembered telling himself for the first time. “It was like a death sentence.”

The closet of the Roman Catholic Church hinges on an impossible contradiction. For years, church leaders have driven gay congregants away in shame and insisted that “homosexual tendencies” are “disordered.” And yet, thousands of the church’s priests are gay.

The stories of gay priests are unspoken, veiled from the outside world, known only to one another, if they are known at all.

Fewer than about 10 priests in the United States have dared to come out publicly. But gay men likely make up at least 30 to 40 percent of the American Catholic clergy, according to dozens of estimates from gay priests themselves and researchers. Some priests say the number is closer to 75 percent. One priest in Wisconsin said he assumed every priest is gay unless he knows for a fact he is not. A priest in Florida put it this way: “A third are gay, a third are straight, and a third don’t know what the hell they are.”

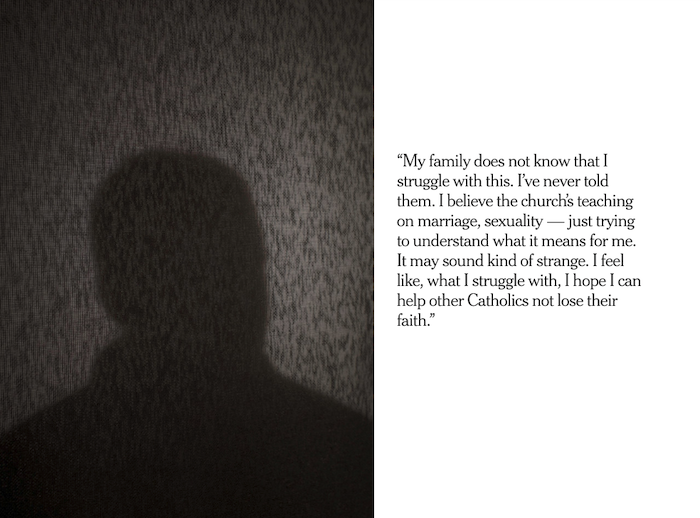

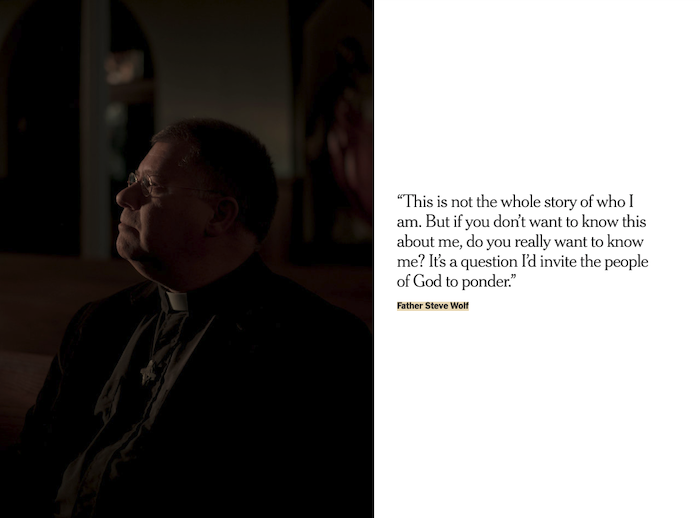

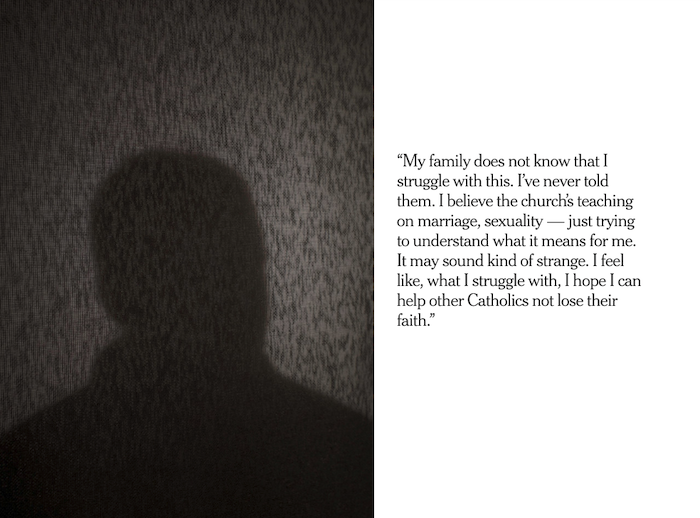

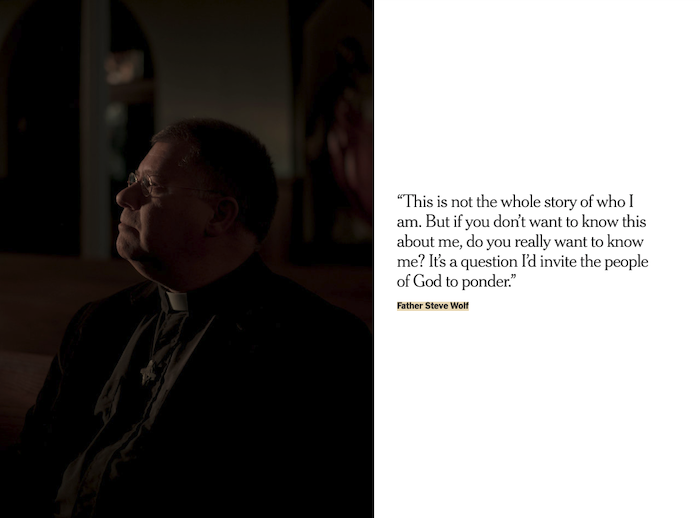

Two dozen gay priests and seminarians from 13 states shared intimate details of their lives in the Catholic closet with The New York Times over the past two months. They were interviewed in their churches before Mass, from art museums on the weekend, in their apartments decorated with rainbow neon lights, and between classes at seminary. Some agreed to be photographed if their identities were concealed.

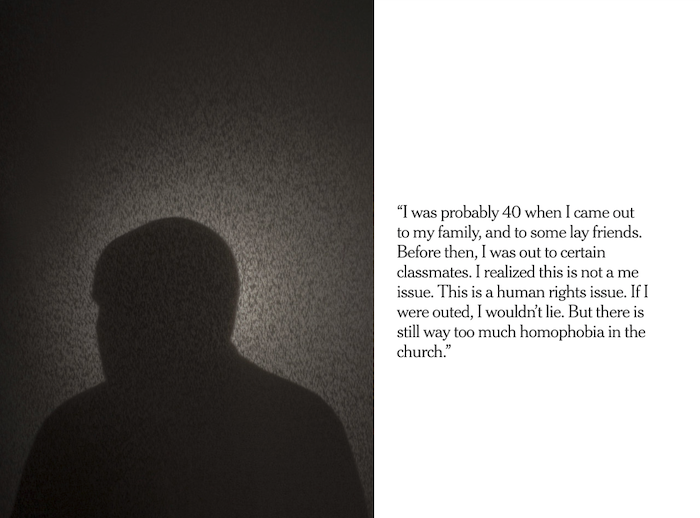

Almost all of them required strict confidentiality to speak without fear of retribution from their bishops or superiors. A few had been expressly forbidden to come out or even to speak about homosexuality. Most are in active ministry, and could lose more than their jobs if they are outed. The church almost always controls a priest’s housing, health insurance and retirement pension. He could lose all three if his bishop finds his sexuality disqualifying, even if he is faithful to his vows of celibacy.

The environment for gay priests has grown only more dangerous. The fall of Theodore McCarrick, the once-powerful cardinal who was defrocked last week for sexual abuse of boys and young men, has inflamed accusations that homosexuality is to blame for the church’s resurgent abuse crisis.

Studies repeatedly find there to be no connection between being gay and abusing children. And yet prominent bishops have singled out gay priests as the root of the problem, and right-wing media organizations attack what they have called the church’s “homosexual subculture,” “lavender mafia,” or “gay cabal.”

Even Pope Francis has grown more critical in recent months. He has called homosexuality “fashionable,” recommended that men with “this deep-seated tendency” not be accepted for ministry, and admonished gay priests to be “perfectly responsible, trying to never create scandal.”

This week, Pope Francis will host a much-anticipated summit on sex abuse with bishops from around the world. The debate promises to be not only about holding bishops accountable but also about homosexuality itself.

“This is my life,” a parish priest in the Northeast said. “You feel like everyone is on a witch hunt now for things you have never done.”

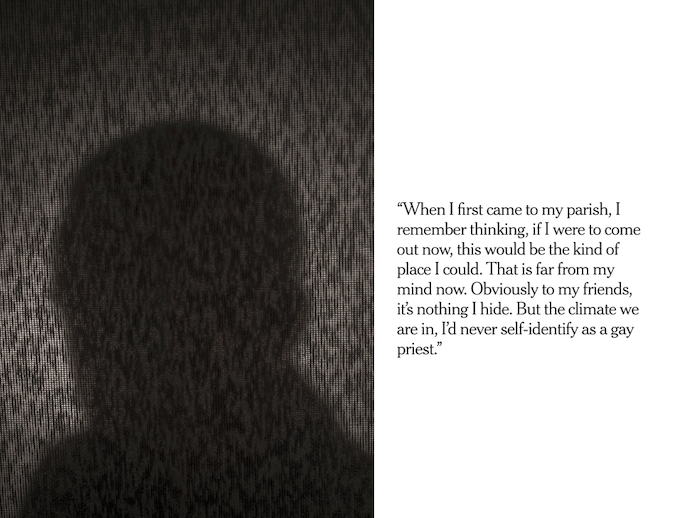

Just a few years ago, this shift was almost unimaginable. When Pope Francis uttered his revolutionary question, “Who am I to judge?” in 2013, he tempted the closet door to swing open. A cautious few priests stepped through.

But if the closet door cracked, the sex abuse crisis now threatens to slam it shut. Widespread scapegoating has driven many priests deeper into the closet.

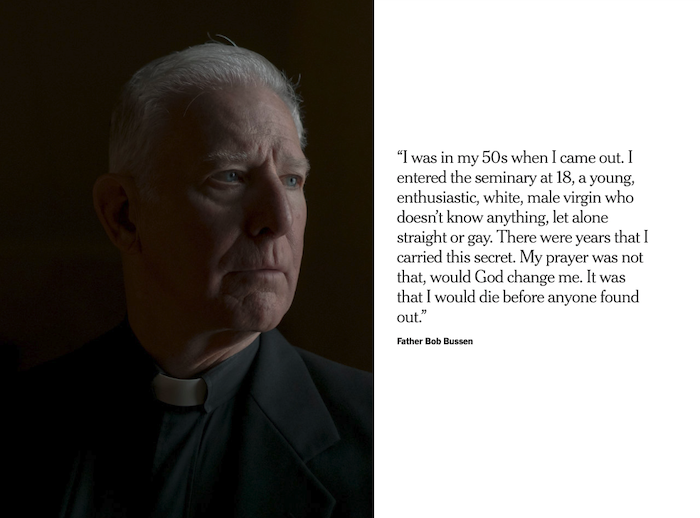

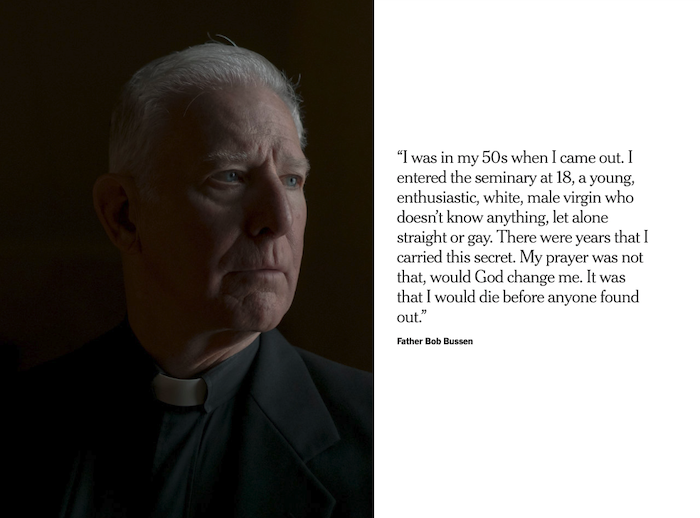

“The vast majority of gay priests are not safe,” said Father Bob Bussen, a priest in Park City, Utah, who was outed about 12 years ago after he held mass for the L.G.B.T.Q. community.

“Life in the closet is worse than scapegoating,” he said. “It is not a closet. It is a cage.”

“You can be taught to act straight in order to survive.”

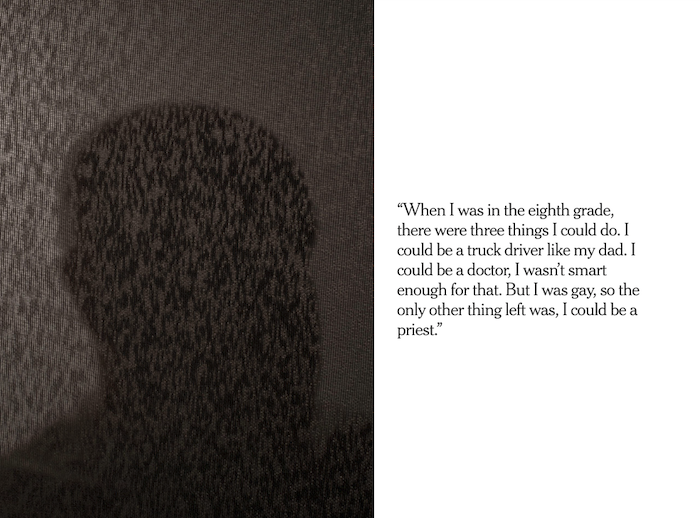

Even before a priest may know he is gay, he knows the closet. The code is taught early, often in seminary. Numquam duo, semper tres, the warning goes. Never two, always three. Move in trios, never as a couple. No going on walks alone together alone, no going to the movies in a pair. The higher-ups warned for years: Any male friendship is too dangerous, could slide into something sexual, and turn into what they called a “particular friendship.”

“You couldn’t have a particular friendship with a man, because you might end up being homosexual,” explained a priest, who once nicknamed his friends “the P.F.s.” “And you couldn’t have a friendship with a woman, because you might end up falling in love, and they were both against celibacy. With whom do you have a relationship that would be a healthy human relationship?”

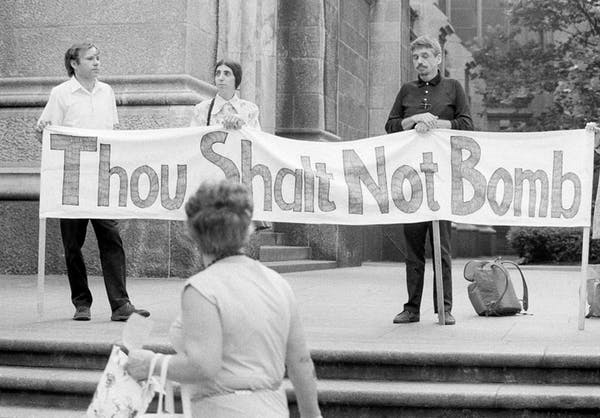

Today, training for the priesthood in the United States usually starts in or after college. But until about 1980, the church often recruited boys to start in ninth grade — teenagers still in the throes of puberty. For many of today’s priests and bishops over 50, this environment limited healthy sexual development. Priests cannot marry, so sexuality from the start was about abstinence, and obedience.

The sexual revolution happening outside seminary walls might as well have happened on the moon, and national milestones in the fight for gay rights like the Stonewall riots, on Mars.

One priest in a rural diocese said the rules reminded him of how his elementary school forced left-handed students to write with their right hand. “You can be taught to act straight in order to survive,” he said.

“I can still remember seeing a seminarian come out of another’s room at 5 a.m. and thinking, isn’t it nice, they talked all night,” the same priest said. “I was so naïve.”

Priests in America tend to come out to themselves at a much later age than the national average for gay men, 15. Many gay priests spoke of being pulled between denial and confusion, finally coming out to themselves in their 30s or 40s.

Father Greiten was 24 when he realized he was gay and considered jumping from his dorm window. He did not jump, but confided his despair in a classmate. His friend came out himself. It was a revelation: There were other people studying to be priests who were gay. It was just that no one talked about it.

He reached out to a former seminary professor who he thought might also be a gay man.

“There will be a time in your life when you will look back on this and you’re going to just love yourself for being gay,” Father Greiten remembered this man telling him. “I thought, ‘This man must be totally insane.’”

But he had discovered the strange irony of the Catholic closet — it isn’t secret at all.

“It’s kind of like an open closet,” Father Greiten said. “It’s the making of it public, and speaking about it, where it becomes an issue.”

One priest, whose parish has no idea he is gay, remembered a backyard cocktail party a few years ago where fellow priests were saying “vile” things about a gay bishop. He intervened, and came out to them. He lost three friends that night. “I broke the code by announcing to them that I was gay,” he said. “It was a conspiracy of silence.”

That is a reason many of the men are out to only a few close friends. The grapevine has taught them which priests in their diocese are gay, whom to trust, and whom to fear.

All priests must wrestle with their vows of celibacy, and the few priests who are publicly out make clear they are chaste.

Still, many priests said they have had sex with other men to explore their sexual identity. Some have watched pornography to see what it was like for two men to have sex. They ultimately found more anguish than pleasure.

One priest had sex for the first time at 62, no strings attached, with a man he met online. The relationship was discovered and reported to his bishop, and he has not had sex since. Another priest, when asked if he had ever considered himself as having a partner, wondered what that even meant. He paused, before mentioning one very special friend. “I fell in love several times with men,” he said. “I knew from the beginning it wasn’t going to last.”

Though open, the closet means that many priests have held the most painful stories among themselves for decades: The seminarian who died by suicide, and the matches from a gay bar found afterward in his room. The priest friends who died of AIDS. The feeling of coming home to an empty rectory every night.

So they find ways to encourage one other. They share books like Father James Martin’s groundbreaking “Building a Bridge,” on the relationship between the Catholic and L.G.B.T. communities. Some have signed petitions against church-sponsored conversion therapy programs, or have met on private retreats, after figuring out how to conceal them on their church calendars. Occasionally, a priest may even take off his collar and offer to unofficially bless a gay couple’s marriage.

Some may call this rebellion. But “it is not a cabal,” one priest said. “It is a support group.”

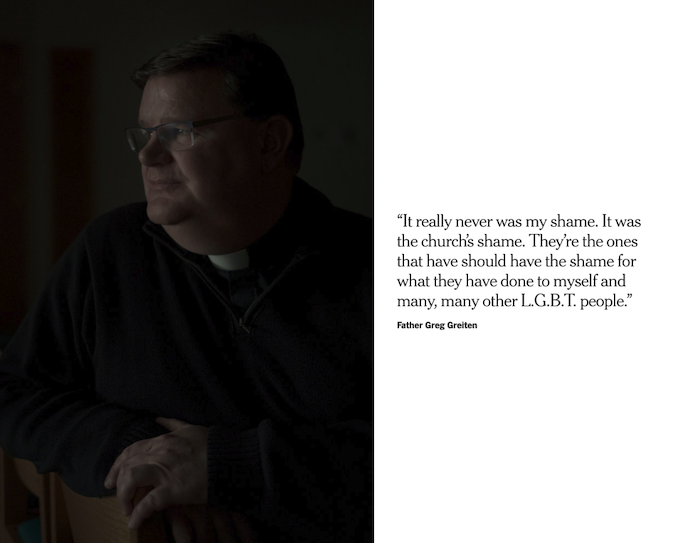

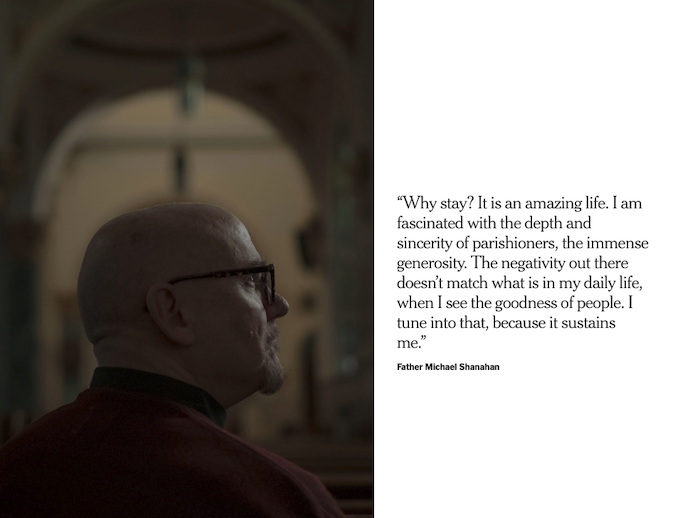

Just over a year ago, after meeting with a group of gay priests, Father Greiten decided it was time to end his silence. At Sunday Mass, during Advent, he told his suburban parish he was gay, and celibate. They leapt to their feet in applause.

His story went viral. A 90-year-old priest called him to say he had lived his entire life in the closet and longed for the future to be different. A woman wrote from Mississippi, asking him to move south to be her priest.

To some church leaders, that outpouring of support may have been even more threatening than his sexuality. Father Greiten had committed the cardinal sin: He opened the door to debate. His archbishop, Jerome E. Listecki of Milwaukee, issued a statement saying that he wished Father Greiten had not gone public. Letters poured in calling him “satanic,” “gay filth,” and a “monster” who sodomized children.

“We have to get it right when it comes to sexuality.”

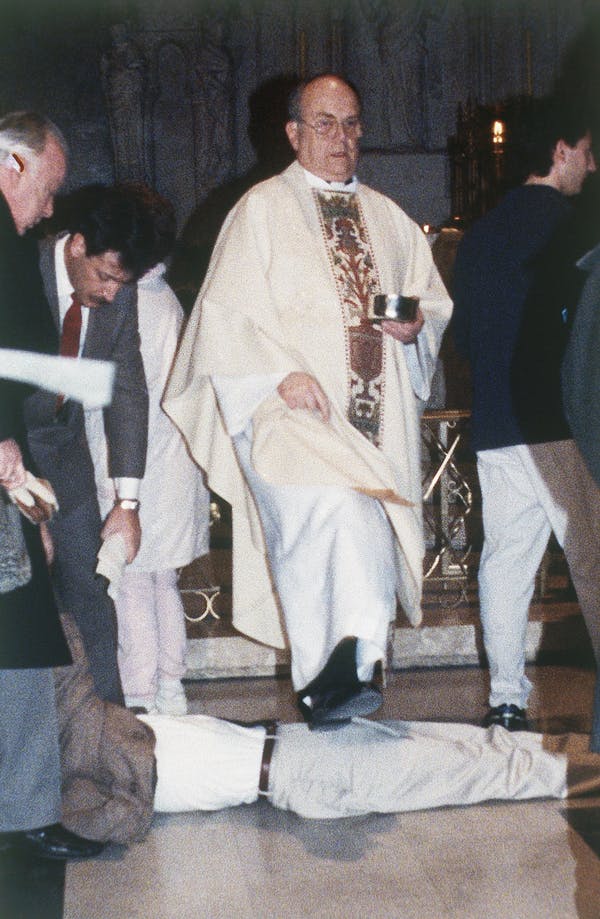

The idea that gay priests are responsible for child sexual abuse remains a persistent belief, especially in many conservative Catholic circles. For years, church leaders have been deeply confused about the relationship between gay men and sexual abuse. With every new abuse revelation, the tangled threads of the church’s sexual culture become even more impossible to sort out.

Study after study shows that homosexuality is not a predictor of child molestation. This is also true for priests, according to a famous studyby John Jay College of Criminal Justice in the wake of revelations in 2002 about child sex abuse in the church. The John Jay research, which church leaders commissioned, found that same-sex experience did not make priests more likely to abuse minors, and that four out of five people who said they were victims were male. Researchers found no single cause for this abuse, but identified that abusive priests’ extensive access to boys had been critical to their choice of victims.

The notion that a certain sexual identity leads to abusive behavior has demoralized gay priests for decades. Days after one man retired, he still could not shake what his archbishop in the 1970s told all the new priests headed to their first parish assignments. “He said, ‘I don’t ever want you to call me to report about your pastor, unless he is a homo or an alchie,’” he said, referring to an alcoholic. “He didn’t even know what he meant when he said homo, because we were all homos. He meant a predator, like serial predator.”

This perception persists today at prominent Catholic seminaries. At the largest in the United States, Mundelein Seminary in Illinois, few ever talk about sexual identity, said one gay student, who is afraid to ever come out. Since last summer, when Mr. McCarrick was exposed for abusing young men, students have been drilled in rules about celibacy and the evils of masturbation and pornography.

“Classmates will say, ‘Don’t admit gays,’” said the student. “Their attitude is that it is gay priests who inflict abuse on younger guys.”

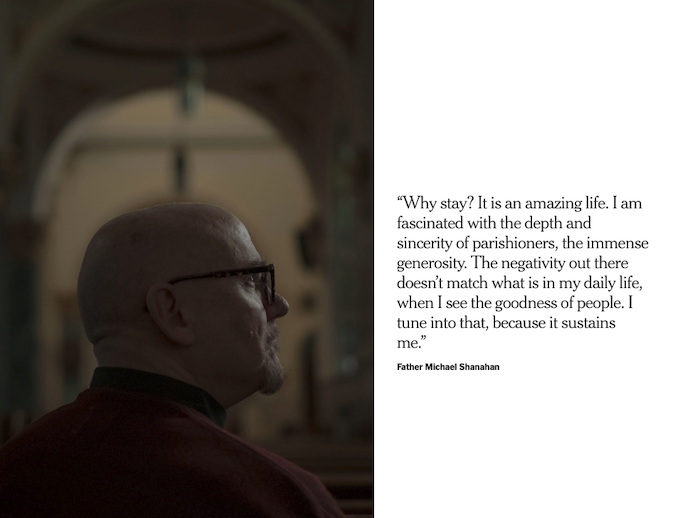

Priests across the country are wondering if their sacrifice is worth the personal cost. “Am I going to leave the priesthood because I’m sick of that accusation?” asked Father Michael Shanahan, a Chicago priest who came out publicly three years ago. “Become more distant from parishioners? Am I going to hide? Become hardened, and old?”

Blaming sexual abuse on gay men is almost sure to be a major topic this week at the Vatican, at a much-anticipated four-day summit on sexual abuse. Pope Francis has called the world’s most powerful bishops to Rome to educate them on the problems of abuse, after high-profile abuses cases in the United States, Australia, Chile and elsewhere.

The event has worried gay priests. A few years after the 2002 scandal, the Vatican banned gay men from seminaries and ordination. When the abuse crisis broke out again last summer, the former Vatican ambassador to the United States, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, accused “homosexual networks” of American cardinals of secretly working to protect abusers. And this week, a sensational book titled “Sodoma” in Europe (“In the Closet of the Vatican” in the United States) is being released that claims to expose a vast gay subculture at the Vatican.

A group of gay priests in the Netherlands recently took the unusually bold step of writing to Pope Francis, urging him to allow gay, celibate men to be ordained.

“Instead of seeing increased accountability on the parts of the bishops, it could become once again a condemnation of lesbian, gay, transsexual people within the church,” said John Coe, 63, a permanent deacon in Kentucky, who came out last year.

Sitting in his parish’s small counseling room, Father Greiten reflected on it all. He wished he could talk to Pope Francis himself. “Listen to my story of how the church traumatized me for being a gay man,” he asked, into the air.

“It’s not just about the sexual abuse crisis,” he said, his voice growing urgent. “They are sexually traumatizing and wounding yet another generation. We have to stand up and say no more sexual abuse, no more sexual traumatizing, no more sexual wounding. We have to get it right when it comes to sexuality.”

For now, Father Greiten was getting ready for his 15th trip to Honduras with doctors and medical supplies. A shadow box hung on the wall behind him. It displayed a scrap of purple knitting, needle still stuck in the top. He calls it “The Unfinished Gift.”

“What if every priest was truly allowed to live their life freely, openly, honestly?” he asked. “That’s my dream.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!