— Researchers look to ‘fraud triangle’ in parish life

Priests who steal are often motivated by resentment, envy, and a desire to cover up for other moral lapses, new analysis has found.

BY The Pillar

Priests who steal are often motivated by resentment, envy, and a desire to cover up for other moral lapses, new analysis has found, adding that isolation and weak oversight can contribute to the rationalization of theft through “moral licensing.”

But the same analysis concluded that a relatively small number of priests have been caught stealing from parishes, and that the priesthood does not seem to attract fraudsters or financial con artists.

A new scholarly article, “Exploring Embezzlement by Catholic Priests in the United States: A Content Analysis of Cases Since 1963,” documented almost 100 instances of stealing by priests, which have sometimes involved hundreds of thousands stolen.

The study aims to assess financial crimes committed by Catholic priests in light of what researchers call the “fraud triangle” — pressure, opportunity, and rationalization.

“The fraud triangle… has proven a remarkably robust analytical device for the understanding of a broad range of financial deviance,” the report said.

“In the religious arena [it] offers several advantages, beyond the irony of its presence. Anecdotal accounts characterize these entities as reluctant and slow adopters of modern business practices including elementary internal controls.”

Researchers Robert Warren and Timothy J. Fogarty compiled documented financial crimes committed by American Catholic priests in the last six decades. They looked at environmental and personal factors, aiming to understand how parish pastors can be tempted into large-scale theft from their parishes.

“Priests are a highly distinctive occupational group,” the report noted, while explaining that while pressures, opportunities, and rationalizations varied case to case, distinctly clerically Catholic elements were identifiable.

The report was published in the January-June issue of the Journal of Forensic and Investigative Accounting.

Crimes of opportunity

The peer-reviewed scholarship looked at 98 cases of priestly fraud committed between the years 1963 through 2020, but discounted three cases in which the fraud was unrelated to the priests’ ministry.

Of the remaining cases studied, more than 90% of priests were serving in parish ministry at the time of their crimes, in which an average amount of nearly $500,000 was stolen, at a median amount of more than $230,000, over an average period of 6 years.

In all of those cases, the authors wrote, the opportunity to steal was consistent with conditions facing virtually all priests in parish ministry – and not only the ability to steal once, but the opportunity “to successfully continue it through time,” the authors explained.

“Catholic priests would seem to have a strong ability to commit fraud,” the article concluded, noting that “they command local positions of unchallenged authority over cash-generating operations with weak internal controls that would detect or deter the misappropriation of resources. For many, priests also exist as citizens above suspicion for misdeeds such as fraud.”

The analysis found that while priestly fraudsters used a variety of ways to steal, four common ways emerged:

“Taking cash directly from the weekly collection and poor box, coercing vulnerable elderly parishioners (primarily widowed females) to gift money to the parish or to the priest personally under false pretenses, diverting checks payable to the parish into non-parish accounts, and improper reimbursement of personal expenses and using secret bank accounts in the church’s name as a slush fund.”

While some of those methods are created by the realities of priestly life, like the potential to abuse moral and spiritual authority in office, the report noted that others are the result of systemic vulnerabilities in the Church’s internal ordering.

The report noted that canon law “still gives the pastor sole control over the parish assets, even though he is obligated to use it for the good of the parish. Thus, a pastor can unilaterally open bank accounts, disperse funds, and sell assets.”

“Parish councils consisting of volunteer parishioners tend to provide ceremonial oversight, often rubber stamping the acts of a priest who most consider a person beyond suspicion,” the report found, while “hierarchical authorities of the dioceses expect parishes to be self-sustaining or to send money upstream and are not generally the source of structure or discipline.”

As a result of infrequent audits in many dioceses, usually undertaken during a change of parish leadership, “detection is left mostly to happenstance,” the report found, noting that only 29.5% of fraud or theft cases were discovered in the course of a routine diocesan audit or parish-level financial controls.

Nearly half of studied cases came to light as a result of whistleblowers, sting operations, or unrelated law enforcement investigations.

But even while administering parishes presents a target-rich environment for fraud, the report found that the data “does not attest to whether Roman Catholic priests are more or less honest than other groups.”

It added that financial crimes were found to have been only committed by a “small fraction of all priests.”

Indeed, the evidence suggests that the priesthood does not attract intentional fraudsters, or those necessarily predisposed to theft. Were that the case, one would expect to see instances of theft arise in the early years of ministry, or begin when the opportunity first presented itself.

Instead, the article said, the cases examined took place later in a priest’s ministry, at an average age of 52 and after an average of more than two decades in ministry.

Under pressure?

A key part of the “fraud triangle” used to analyze patterns of theft is the pressure to commit a crime in the first place. Among priests, the report found, “the collected evidence points to few conventional pressures.”

Common drivers of first-time financial crime include sudden material necessity, like the loss of employment or the need to provide for a family’s basic needs — all of which, the report noted, were not present for Catholic priests.

Other kinds of urgent financial necessity did arise in a minority of cases, they found, including gambling debts (8.4% of cases) and, more often, the need for financial resources to cover other moral failings, usually sexual: in nearly 12% of cases, money was taken to support “illicit relationships.”

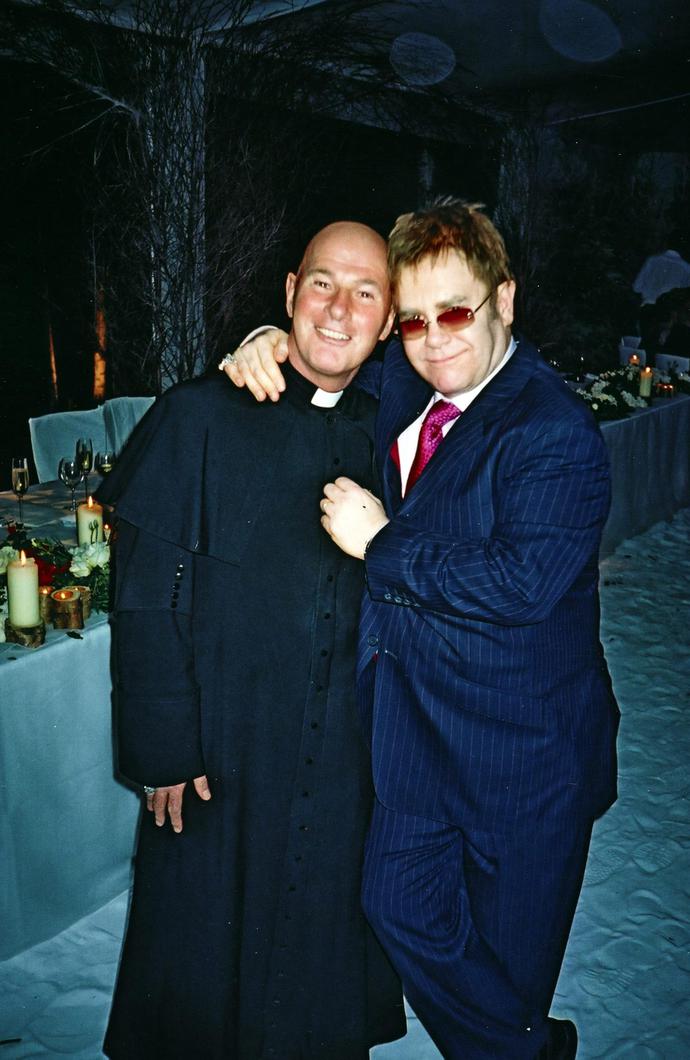

Among such cases are “a priest in Virginia [who] embezzled $591,000 to support his secret wife and three children; a priest in Connecticut [who] used about $1,000,000 in church funds to pursue romantic relationships with at least three men before abandoning his parish; and a priest in Pennsylvania [who] embezzled at least $32,000 to spend on men he met on a dating website.”

Outside of acute financial needs, the report said, ordinarily a key pressure to steal comes from maintaining a publicly successful lifestyle and the appearance of material success to maintain personal reputation. But, the authors pointed out, the reverse pressure is actually present for Catholics priests, for whom an ostentatious lifestyle could actually detract from their social standing.

Instead, they said, “the incentives to steal could be summed up as a desire to live a life very different from that usually associated with a priest.”

“A recent study found that newly ordained priests were paid between $26,000 and $30,000 depending on their geographic area, with lead priests (pastors) earning between $26,000 and $34,000,” said the article.

“Although the diocesan priest also enjoys a plethora of other benefits including free room and board, health insurance, a car allowance, and a retirement plan, these rates of pay put them barely above minimum wage rates for a job that is quite demanding.”

This, the report said, can lead to some priests experiencing a sense of frustrated entitlement, and even jealousy, when compared to the relative lifestyles of ministers of other religions and even their own parishioners.

“The pressure felt by a priest might be closely associated with the very occupation itself, or more precisely the demands that the role makes upon its incumbents” said the report. “The pressure felt by priests might not be in the nature of a sudden emergency or an unexpected reversal, but instead be the grinding and persistent force of envy.”

More than half of the cases studied showed that priests spent stolen or misappropriated funds “primarily to support a lavish lifestyle.”

“Many of these priests used the ill-gotten gain to support second and third homes,” the study found, while noting that in a handful of cases the priests said they were trying to provide for their own retirement. In one extreme case, a priest in New York City “was caught with a handgun and $50,000 in cash told police it was his ‘401-K plan.’”

‘Not really stealing’

A key factor in the cases studied is the phenomenon of “moral licensing,” or the rationalization of the financial crime by the priest. In many cases, the report said, stealing priests believed that taking parish money, or using it for personal benefit, was justifiable self-compensation for hard work, long hours, or even a more general lack of remuneration or appreciation for other good behavior .

“Those that took money to spend in hedonistic ways and on purely personal pursuits did not tend to profess their entitlement as a general rule,” the report found. “In that priests often see themselves as independent contractors or entrepreneurs, they are more willing to buck the hierarchical authority of their organization in the name of a personal view of what is in the best interests of the clientele.”

“The latter may be a highly occupationally specific fraud rationalization.”

The article also noted that the “‘it’s not really stealing’ rationalization” was explicitly cited by six priests caught stealing, each of whom argued that canon law gave them authority to spend parish funds wherever they wished.

Sometimes that argument worked, the report found. A judge in Arizona dismissed an indictment against a priest who argued that he was canonically allowed to rent a parcel of real property with parish money even without a proper parish purpose.

But the “good purpose” line of reasoning also has “considerable variation,” the authors wrote.

“Two pastors indicated that they maintained secret bank accounts to have more funds available to the parish. For instance, a diocesan priest from Connecticut kept an ‘off the books’ bank account to ensure the parish had enough funds to operate in the summer months when regular church attendance slipped, although doing so had been expressly forbidden by the bishop. During a four-year period, the priest spent $2,000,000 from that account, with $1.7 million going to various legitimate projects for the parish and school.”

“However,” the report noted, “the priest spent the remaining $300,000 to enjoy a lavish lifestyle and maintain an alleged inappropriate relationship with a male friend with whom he maintained an apartment in New York City.”

The report also highlighted that, in a number of cases, stolen and misappropriated parish funds were not actually used for the benefit of the priest who took them.

Of the 95 cases examined, seven of the priests used their ill-gotten gains to support family members or charities in foreign countries: One priest in Wisconsin pocketed parish funds to buy goods sent to the poor in his native Nigeria, a priest in Kansas took cash from the collection plate to take back to Mexico for his family, and priest from Pennsylvania skimmed funds from his parish to support a charity hospital in his native Lebanon.

Crime and punishment

“Opportunity can also be judged by final consequences,” the authors noted, and flagged that even when caught and convicted, “long sentences were the exception rather than the rule,” and in many cases priests faced only internal discipline by Church authorities.

While in each of the 95 cases examined the priest unquestionably stole Church funds, only 58 were actually charged with embezzlement, fraud, or larceny, and almost a third of those who were criminally convicted were subsequently returned to ministry, in some cases even when there were exacerbating factors to the crime:

“A former pastor (and self-described ‘sexaholic’) in Minnesota who embezzled $73,733 to finance his pilgrimages to strip clubs and massage parlors pleaded guilty, served a short stint in the county prison with work release privileges, and was eventually returned to ministry as an assistant pastor,” the report noted, while “a priest in Nevada who served 36 months in federal prison after gambling away $650,000 in parish funds, was transferred to another diocese where he became head of human resources.”

“Opportunity is abetted by the probable awareness that those detected will not be severely punished nor will there be sizable reputational consequences,” the report concluded.

—

While the report identifies a number of unique aspects to fraud by U.S. Catholic clergy, it also underscores that those are essentially sector-specific iterations of the “fraud triangle” of pressure, opportunity, and rationalization found everywhere.

Although Catholic parish and diocesan structures present a “strong and obvious” opportunity for fraud and theft, and their reliance on the personal trustworthiness of priests can actually increase the risk of stealing and drive down the chances of being caught, the article’s authors stress that priests appear no more likely to succumb to temptation than anyone else, and the kind of long term, high value thefts examined represent a tiny minority of priests..

The article explains that while certain idiosyncrasies of fraud in parish life do emerge from the data, the authors could not claim a predictive model for identifying potential fraudsters.

But the report does highlight that “the pressure felt by a priest [to steal] might be closely associated with the very occupation itself, or more precisely the demands that the role makes upon its incumbents.”

Across cases, whether motivated by the financial gain itself, a need to cover up illicit relationships, or even the conceit that a priest can decide for himself how any and all parish funds are spent, the findings of the report would seem to point to an underlying commonality of isolation, disaffection with ministry, and a disordered relationship with Church structures among clerical financial criminals.

—

Warren and Fogarty’s findings noted that priests are unique among financial criminals, and that large scale or systematic embezzlement in religious institutions is often under-studied, even while religious institutions often involved considerable amounts of cash accounted for on a basis of personal trust.

In addition to calling for better mechanisms of financial oversight and accountability, the study’s findings highlight the need for ongoing spiritual and personal formation in priests throughout their ministry.

The researchers explained that focusing on Catholic priests presented a unique opportunity for study, both because the Catholic Church is the country’s largest religious denomination, and because it allowed for a study sample with broadly consistent hierarchical and financial policies.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!