By Philip Pullella

Some Catholic women are calling to remove the barriers that prevent them from reaching the highest positions in their church’s leadership.

They say women should be able to vote in major policy meetings. They want Pope Francis to act on his promise to put more women in leadership positions within his administration, known as the Holy See. And some women want to become priests.

Synod

“Knock, knock! Who’s there? More than half the Church!” a group of Catholic women shouted outside the Vatican on October 3. That was the first day of this year’s meeting, or synod, of bishops from around the world.

The meeting brings together some 300 bishops, priests, nuns and other members of the church. Only about 35 are women. Not surprisingly, the position of women in the Catholic Church has been a major issue at the month-long meeting. The subject has come up in speeches on the floor, in small group discussions and at news conferences.

Only “synod fathers” are permitted to vote on the meeting’s final policy suggestions. The suggestions are then sent to the pope, who will take them into consideration when he writes his own document. Others involved are non-voting observers or experts.

Some of the attendees have pointed to what they say is a problem with these rules.

For example, this year two men who are not officially priests are being permitted to vote as leaders of their religious orders. But Sister Sally Marie Hodgdon is the leader of her religious order, and she cannot vote.

“I am a superior general,” Hodgdon told reporters. “I am a sister. So in theory … you would think I would have the right to vote.”

The membership of female religious orders is about three times larger than that of male orders.

Seeking change

An internet-based petition demanding that women have the right to vote at synods has collected 9,000 signatures since the start of this meeting. It is supported by 10 Catholic organizations seeking change in the Church. These changes include greater rights for women and homosexuals and greater responsibilities for non-priests.

“If male religious superiors who are not ordained can vote, then women religious superiors who are also not ordained should vote. With no … doctrinal barrier, the only barrier is the biological sex of the religious superior,” the petition reads.

The effort has won some powerful supporters.

At a news conference on October 15, leaders of three major male religious orders expressed support for changes in synod rules. Leaders of the Jesuits, the Dominicans and one branch of the Franciscans asked that women be permitted to vote in the future.

Support also came from Cardinal Reinhard Marx. He is the archbishop of Munich, president of the German Bishops Conference and one of the most influential Catholic leaders in Europe. In a speech to the synod, Marx said the church’s leaders must answer the questions young people have about equal rights for women.

“The impression that the Church, when it comes to power, is ultimately a male Church must be overcome in the universal Church and also here in the Vatican,” he said. “It is high time.”

Women in the Vatican

Five years ago, Pope Francis promised to put more women in leadership in his administration and Vatican City. Women are eligible for top positions in 50 departments, but only six hold such roles. None leads a department.

In June, Francis told the Reuters news service he had to “fight” resistance within the church to appoint 42-year-old Spanish reporter Paloma Garcia-Ovejero. He made her deputy head of the Vatican’s press office.

But the pope’s critics say he is moving too slowly. Sister Maria Luisa Berzosa Gonzalez is taking part in the current synod. She thinks it is time for change — in the synod, and in the wider Church. The 75-year old Spanish nun has spent her life educating the poor in Spain, Argentina and Italy.

“With this structure in the synod, with few women, few young people, nothing will change. It should no longer be this way,” she told Reuters.

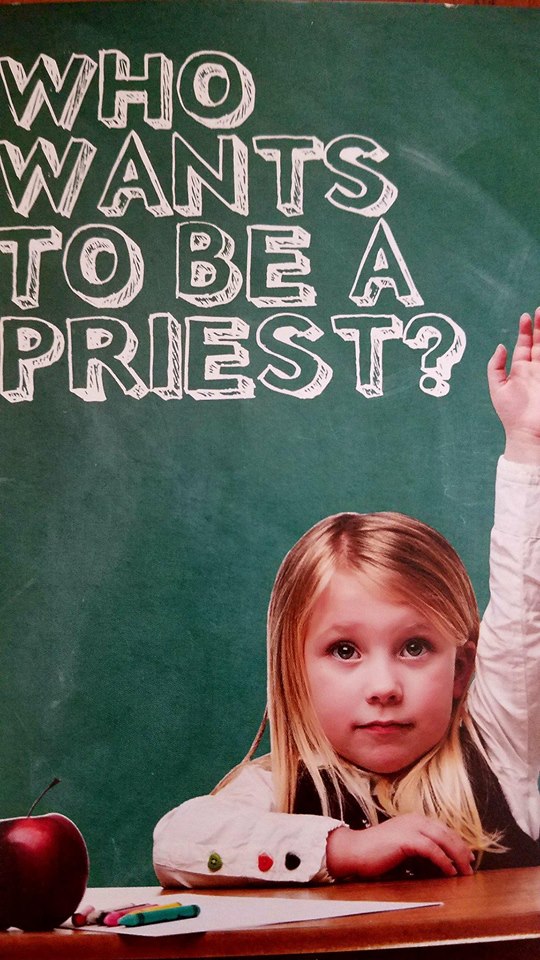

The Catholic Church teaches that women cannot become priests because Jesus chose only men to help form the religion.

But supporters of a female priesthood say Jesus was just following the rules of society at the time. Kate McElwee is the Rome-based executive director of the Women’s Ordination Conference, a U.S. group. She organized the protest on the synod’s opening day.

“Some women feel called by God to be priests … just as men do,” said McElwee.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!