By John Gehring

It has been a season of anguish and rage for Catholics. Sixteen years after the Boston Globe uncovered widespread clergy sexual abuse in a city where the church’s powerful influence once defined a brand of swaggering American Catholicism, those chilling words—“predators” and “cover-up”—are again back in the headlines. The first explosion went off in early summer. Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington and a prominent church leader who traveled the world on social justice missions, was removed from ministry after an investigation found credible allegations that he sexually abused a teenager as a priest. Reports also surfaced that McCarrick, who now holds the ignominious title of the first American to resign from the College of Cardinals, routinely sexually harassed seminarians. Not even two months later, a Pennsylvania grand jury report detailed a horrifying history: More than a thousand children and young people were abused by hundreds of priests in six dioceses across the state over the past seven decades. This staggering scale of institutional evil shattered any lingering illusions that the abuse crisis was isolated. The culture of abuse and cover-up is systemic. After consulting with the FBI, the grand jury described the way church officials acted as “a playbook” for concealing the truth. The bombshells didn’t end there.

The latest eruption landed with even more impact, and has sparked perhaps the most bitter round of church infighting in the history of the U.S. Catholic Church. On a Sunday in late August, conservative Catholic media outlets in the United States and Italy released a stunning 11-page letter from the former Vatican ambassador to Washington, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò. The testimony, as the nuncio described it, made a series of sweeping allegations without documented proof, the most dramatic being that Pope Francis ignored Viganò’s warnings about McCarrick’s behavior. In the late 2000s, he alleges, Pope Benedict XVI had ordered McCarrick to “a life of prayer and penance,” prohibiting him from saying Mass or speaking in public. Francis, the retired nuncio wrote, not only disregarded that supposed order but made McCarrick a “trusted counselor” who helped the pope appoint several progressive-minded bishops in the United States, including Cardinals Blase Cupich in Chicago and Joe Tobin of Newark—both viewed as prominent Francis allies. Most audaciously, Viganò urged Pope Francis to resign “to set a good example for cardinals and bishops who covered up McCarrick’s abuses.”

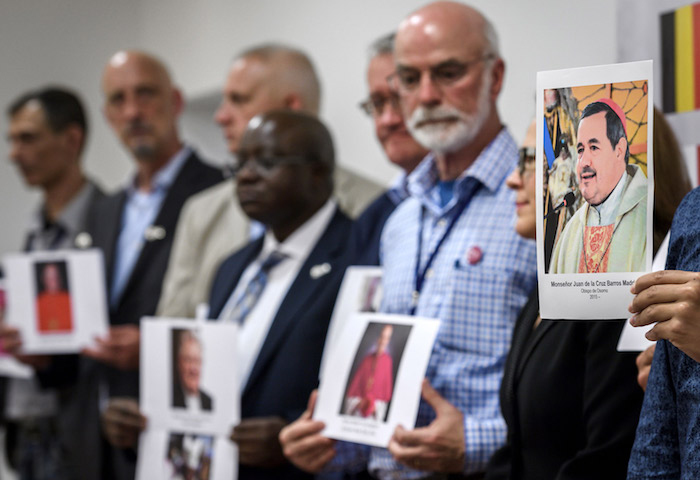

Pope Francis, addressing reporters during an in-flight press conference after the news broke at the end of his recent visit to Ireland, essentially dismissed the allegations, encouraging journalists to uncover the truth. “I think this statement speaks for itself, and you have the sufficient journalistic capacity to draw conclusions,” he said. Reporters from multiple outlets have already pointed out discrepancies between Viganò’s testimony and the historical record. While the former ambassador claims that Pope Benedict XVI ordered McCarrick to never say Mass and withdraw from public view, reporters quickly produced photographs, videos, and other evidence of the disgraced cardinal presiding at Mass, including in Rome at St. Peter’s Basilica during Benedict’s papacy. McCarrick continued to attend papal functions during Benedict’s tenure, received awards from Catholic institutions, sat on the board of Catholic Relief Services, and made dozens of international trips. In a 2012 photograph, Viganò is seen congratulating McCarrick at a gala dinner sponsored by the Pontifical Missions Society in New York. More recently, the former ambassador has backpeddled, telling LifeSiteNews, one of the conservative Catholic media outlets that originally released Viganò’s letter, that the alleged sanctions imposed on McCarrick were “private” and that neither he nor Pope Benedict XVI were able to enforce them. The retired pope’s personal secretary, Archbishop Georg Gänswein, told the Italian media outlet ANSA that reports of Benedict confirming some of the accusations in Viganò’s testimony were “fake news, a lie.” Last week, in a letter obtained by Catholic News Service, a top official from the Vatican’s secretary of state office acknowledged receiving allegations about McCarrick’s behavior with seminarians as far back as 2000, during the papacy of John Paul II. A statement released this week from members of the pope’s advisory council of nine cardinals expressed “full solidarity with Pope Francis in the face of what has happened in the last few weeks,” and noted that the Holy See is “formulating possible and necessary clarifications.”

While the daily developments and details of Viganò’s claims should be thoroughly investigated no matter where they lead, there is no way to understand this saga without recognizing how the former ambassador’s claims are part of a coordinated effort to undermine the Francis papacy. The Viganò letter is as much about power politics in the church as it is about rooting out a culture of abuse and cover-up. A small but vocal group of conservative Catholic pundits, priests, and archbishops, including the former archbishop of St. Louis Cardinal Raymond Burke, have led what can be described without hyperbole as a resistance movement against their own Holy Father since his election five years ago. Pope Francis, the insurgents insist, is dangerously steering the church away from traditional orthodoxy on homosexuality, divorce, and family life because of his more inclusive tone toward LGBT people and efforts to find pastoral ways to approach divorced and remarried Catholics. These conservative critics, many of whom essentially labeled progressive Catholics heretics for not showing enough deference to Pope Benedict XVI, are not discreet in their efforts to rebuke Francis. Last year, in a letter to the pope from the former head of the doctrine office at the U.S. bishops’ conference in Washington, Fr. Thomas Weinandy accused the pope of “demeaning” the importance of doctrine, appointing bishops who “scandalize” the faithful, and creating “chronic confusion” in his teachings. “To teach with such an intentional lack of clarity, inevitably risks sinning against the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of truth,” the priest wrote in remarkably patronizing language more befitting a teacher correcting a student than a priest addressing the successor of Peter.

Viganò’s testimony therefore should not be read in isolation or as an aberration, but as the latest chapter in an ongoing campaign to weaken the credibility of Pope Francis. Political, cultural, and theological rifts among Catholics are nothing new in the church’s 2,000-year history, but Viganò’s call for the pope’s resignation has set off the ecclesial version of a street fight. “The current divisions among Catholics in the United States has no parallel in my lifetime,” Stephen Schneck, the former director of the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at Catholic University of America, said in an interview. Bishops who usually take pains to show unity in public have issued dueling statements on Viganò’s letter that reflect this discord. Cardinal Tobin, who was appointed by Francis, sees Viganò’s accusations being used by the pope’s opponents to gain leverage. “I do think it’s about limiting the days of this pope, and short of that, neutering his voice or casting ambiguity around him,” the cardinal told The New York Times. Some conservatives in the hierarchy have cheered Viganò. Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, issued a statement just hours after the letter was made public and ordered priests in his diocese to read his statement during Mass. “As your shepherd, I find them credible,” the bishop wrote in response to Viganò’s allegations.

In part, the letter feels like a manifesto written with all of the standard Catholic right talking points and grievances. This is especially the case when it comes to how the church approaches sexuality. The former nuncio, who consulted with a conservative Italian journalist before releasing the text, writes about “homosexual networks” in the church that “act under the concealment of secrecy and lies with the power of octopus tentacles, and strangle innocent victims and priestly vocations, and are strangling the entire Church.” Viganò laments church leaders “promoting homosexuals into positions of responsibility.” This language and demonization echo the arguments some Catholic conservatives have made for years in an effort to blame the clergy-abuse crisis on gay clergy, and more broadly to challenge the advance of LGBT rights in the secular culture.

Viganò is not a newcomer to these fights. During his time as nuncio in Washington, he broke with ambassadorial norms of carefully avoiding becoming publicly enmeshed in hot-button political disputes by appearing at an anti-gay rally in 2014 organized by the National Organization for Marriage. Speaking at the event outside the U.S. Capitol, San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone said Viganò’s participation “signifies the presence and support of Pope Francis.” But it was during Pope Francis’ 2015 trip to the United States when Viganò really went rogue, working with Liberty Counsel, a conservative legal group, to enlist the pope into American culture wars by hastily arranging a meeting between Francis and Kim Davis, the county clerk in Kentucky who refused to give marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The brief meeting, at the nuncio’s residence, blew up into a fiasco that threatened to spoil the pope’s successful first visit to the United States. Conservative leaders in the church attempted to frame the meeting as the pope choosing sides in the Davis controversy. Vatican officials immediately denied that and distanced themselves from Viganò’s decision to orchestrate the meeting. Instead, the Vatican highlighted a meeting the pope had at the embassy with a gay former student and his partner.

In his letter, Viganò specifically names the Rev. James Martin, a Jesuit priest and prominent editor at America magazine, as an example of how the church’s teachings about homosexuality have been derailed under Francis. In his writings, television appearances, and most recently during a speech at the Vatican-sponsored World Meeting of Families, Martin has urged the church and LGBT Catholics to dialogue together. Even though he doesn’t call for a change in church teaching on same-sex marriage and has the backing of several American cardinals, the media-savvy priest, who has a wide following on social media, is a bogeyman for a network of Catholic right groups. Last fall, the seminary at Catholic University rescinded a speaking gig for Martin because of the manufactured controversies surrounding the priest. “While the contempt directed at gay clergy is coming from just a handful of cardinals, bishops and priests, as well as a subset of Catholic commentators, it is as intense as it is dangerous,” Martin recently wrote in America. Two American bishops, responding to Viganò’s letter, give credence to Martin’s argument. “It is time to admit that there is a homosexual subculture within the hierarchy of the Catholic Church that is wreaking great devastation in the vineyard of the Lord,” Bishop Robert Morlino of Madison, Wisconsin, wrote in a letter to Catholics in his diocese. Cardinal Burke told a conservative Italian newspaper that a “homosexual culture” has “roots inside the church and can be connected to the drama of abuses perpetuated on adolescents and young adults.” A detailed study of the causes and context of clergy abuse, led by researchers at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice after the Boston scandals erupted, found no statistical evidence that gay priests were more likely to abuse minors. A witch-hunt mentality toward gay clergy nevertheless persists. Viganò’s letter only energizes that ugly tendency.

There is a certain irony that Archbishop Viganò wants to target a supposed “homosexual culture” in the church and claim the mantle of truth and transparency on clergy abuse. His record and credibility on those counts are checkered. Two years ago, when documents were disclosed as part of a criminal investigation of the St. Paul-Minneapolis archdiocese, a memo from a Catholic priest alleged that in 2014 Viganò ordered two auxiliary bishops to end their investigation of then-Archbishop John Nienstedt over his alleged misconduct with adult men, including seminarians, when he was serving in another diocese. The memo stated that a local law firm’s investigation into the allegations found compelling evidence against the archbishop, and that archdiocese officials agreed that Nienstedt should resign. But after Nienstedt allegedly met with Viganò to persuade him those claims were made by critics who disagreed with his vocal opposition to same-sex marriage, the memo said, the nuncio ordered the investigation to end quickly and told the archdiocese to destroy a letter from auxiliary bishops to him objecting to that decision. Viganò has recently denied those charges. Citing his own failure of leadership, Nienstedt voluntarily resigned in 2015 after prosecutors accused the archdiocese of repeatedly ignoring warning signs of an abusive priest. That priest was later defrocked and sent to prison for abusing boys in his parish.

The swirling accusations and counter-responses surrounding the former ambassador’s letter highlight the influence of a close-knit, well-funded conservative Catholic network. Viganò’s letter was not first reported on by secular news sources or down-the-middle Catholic media. He released the text to the National Catholic Register and LifeSiteNews, two outlets that have often served as a hub for Catholic commentary critical of the pope’s reforms. The Register’s Rome correspondent, Edward Pentin, is a leading critic of the Francis papacy, and the Register’s parent company, Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN), mixes traditionalist Catholic programming with conservative political and religious commentators often more aligned with Donald Trump than Pope Francis.*

The New York Times reported that before the letter was published, Viganò “shared his plan to speak out” with Timothy Busch, a wealthy Catholic lawyer, donor, and hotel magnate who founded a Napa-based winery where conservative bishops, philanthropists, and the occasional Republican politician meet each summer for prayer and networking. Busch is also on the board of EWTN. “Archbishop Viganò has done us a great service,” Busch said in a recent interview with the Times. “He decided to come forward because if he didn’t, he realized he would be perpetuating a cover-up.” Busch should be viewed with skepticism when it comes to this recent interest in holding church leaders accountable for clergy abuse. His own Napa Institute employed the services of Archbishop Neinstedt even after the archbishop resigned in the wake of clergy abuse scandals in Minneapolis. In a recent email sent to Napa Institute supporters, Busch denied that he was consulted on the letter before publication.

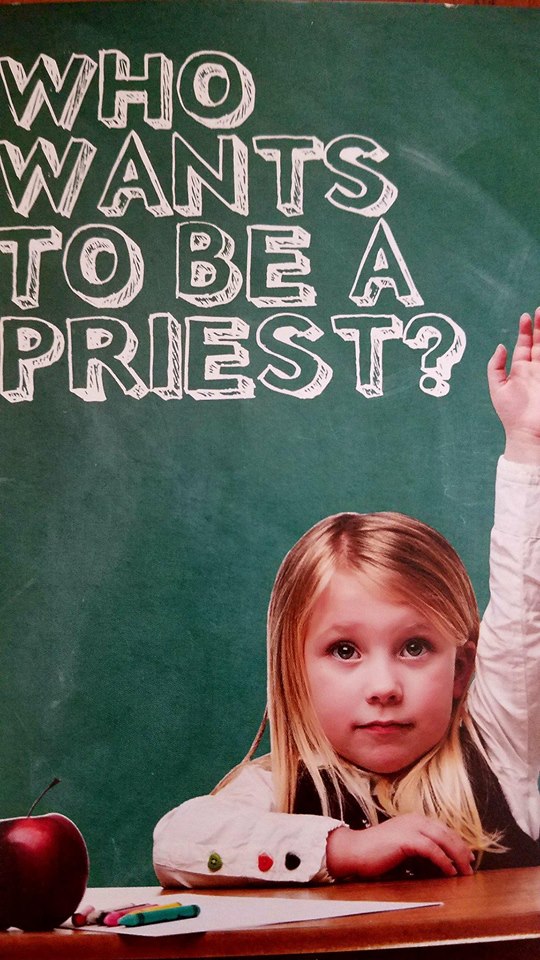

It still remains to be seen how many of the accusations leveled by Archbishop Viganò will stand up under scrutiny. His letter is part and parcel of an anti-Francis movement. Some Catholic networks on the right, which baptize themselves self-appointed watchdogs of orthodoxy and want to undermine the pope and his allies, will continue their campaigns. None of this gives a pass to any church leader, especially Pope Francis, on the sex-abuse crisis. Even Francis’s allies acknowledge that while he has spoken out for victims, he has not created systems to hold bishops accountable for enabling a clerical culture where abuse and cover-up flourish. If the Catholic hierarchy is able to emerge from this crisis with any credibility, it will only happen when a patriarchal hierarchy recognizes that nothing less than radical reform is needed. This reality includes making sure that lay people, especially women, are empowered. Kerry Robinson, founding executive director of the Leadership Roundtable, which began after the sexual abuse revelations in Boston, asks the right question. “How compromised is the Church by failing to include women at the highest level of leadership and at the tables of decision making?” she told me. “This is a matter of managerial urgency.” Internecine fights between Catholic factions that weaponize the abuse crisis to advance agendas might be inevitable in a deeply polarized church, but only deepen the wounds of survivors and prevent future abuses. The Catholic Church must radically reform a culture where clericalism privileges secrecy and abuse of power. Dismantling that system will require an uncomfortable shift away from an institutional mentality that views clergy and bishops as a special caste. Catholics at the grassroots, on the left and right, will need to lead this revolution together.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!