As Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger was head of the Catholic Church from 2005 to 2013. Using archival footage and conversations with contemporary witnesses, this film provides insight into the rise and fall of the German pope.

Alliance, Support & Activism

By Serene Jones

In a few days, Christians around the world will celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ. They will recount how Mary and Joseph made the long, hard journey to Bethlehem and how she gave birth to Jesus in a manger.

It’s a story with beautiful themes of God’s humble love, tenderness and vulnerability. But this holiday season, there’s a part of this story that it’s time to move past: Mary’s purported virginity.

I’m a theologian and am very familiar with the biblical stories of the birth of Jesus, as well as the many views of Mary’s virginity. For centuries, religious scholars have debated whether Mary was in fact a virgin, or whether this interpretation is based on a mistranslation of the Bible.

Regardless of the truth, one thing is for certain: The focus on Mary’s virginity created the rationale behind centuries of harmful views about virginity and perfect womanhood — how we should dress, act and approach our sexuality. These views are, in turn, tied to the gross inequalities women face still 2,000 years later — from the wage gap to attacks on reproductive rights.

For centuries, Christians have held that Mary was herself conceived immaculately — that is, perfectly free of sin and therefore fit to be a pure vessel to carry Jesus. Then, when Mary was a teenager — and importantly, still a virgin — the Holy Spirit conceived Jesus, another perfect, sinless child. Many Christian scholars say that Mary remained a virgin for the rest of her life.

Theologians have long questioned these beliefs, even as religious leaders have used Mary’s purported virginity as a model for how women should behave. Sex is sin. Abstaining from sex is saintly.

St. Augustine was one of several church fathers who characterized sex for pleasure as a sin because it diverted one’s attention away from God. His work created a strong connection between purity and virginity, and laid the groundwork for countless social movements to control and shame women’s sexuality.

Today, this view remains very much alive. In many U.S. conservative Christian communities, women are still instructed that it is their duty — and notably, not the duty of men — to eschew sex for pleasure and to have sex only after marriage and only for reproduction

They are duly told to refrain from dressing in a way that draws male attention. They must reject sexual advances from others and repress their own sexual urges. They wear purity rings and, in a few places, still attend purity balls — at which daughters promise their fathers that they will remain virgins until marriage. Unsurprisingly, many women who are raped or assaulted don’t report it because they don’t want to be considered “tainted.”

Similar mindsets can be found elsewhere, and in other faiths. Honor killings remain a fact of life in some countries, while others criminalize premarital sex and put women who have committed adultery to death.

In sum, a woman’s worth is greatly dependent on how “pure” she is perceived to be, and a woman’s sexual agency is at best ignored and at worst punished.

This shaming of women goes against God’s most basic teachings. In one of Jesus’ pivotal parables, recounted in the Gospel of John, he teaches the opposite lesson: A woman accused of adultery is brought before Jesus by a mob that wants to stone her to death. Instead of condemning her, however, Jesus famously responds that only those without sin should cast the first stone. Not surprisingly, no stones are thrown.

The truth is, Mary’s virginity is superfluous and turns a story that is supposed to be about the love of God into a tale that oppresses women. Instead of focusing on Mary’s sexuality, let’s celebrate the true glory of the season.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

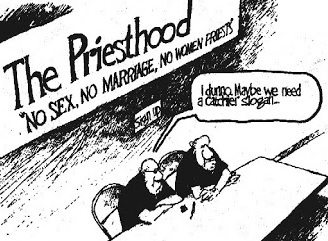

Pope Francis has helped open the door to allowing married men to become priests, albeit in just one region of the Amazon for now. He has made environmentalism a major focus of his papacy. Yesterday he gave a shout-out to Greta Thunberg and thanked journalists for doing their jobs, rather than calling them enemies of the people. He’s decried income inequality and nationalism and spoken out on behalf of gay people, Muslims, immigrants, and the poor.

This pastoral approach has made him one of the clearest and most humane voices crying out in the wilderness today. Has it also made him a revolutionary?

Yesterday, Francis wrapped up a month-long synod, or meeting of bishops, at the Vatican dedicated to the Amazon, a region the bishops called “a wounded and deformed beauty, a place of suffering and violence.” Their list of recommendations to the pope is nothing less than an environmentalist manifesto, in which they recommended that destroying the environment should be considered a sin. (Their requests are nonbinding but set a tone; Francis said he will try to respond to them before the end of the year.)

The bishops also asked Francis to lift the 1,000-year-old ban on priestly celibacy to allow married men who are already ordained as deacons to become priests in some areas of the Amazon. There, a priest shortage means the faithful can go for long stretches without receiving Communion and other sacraments that only priests can deliver. This could very well revolutionize the Church worldwide. If a door opens in one country, it might open in another. (Or it could be limited to the Amazon.)

Francis’s method, and the method of the synod, is one of listening and reflection, then some consensus, and charting a path forward through discernment. The path Francis has been taking, though, leads directly into a larger culture war, one that pits progressives against traditionalists.

And so the synod offered ample opportunity for Francis’s many vocal critics—including conservative Catholics in the United States, who are intertwined with the political right—to accuse the pope of breaking orthodoxy and watering down Church doctrine, such as the bishops’ recommendations to allow more room for indigenous traditions in Catholic ritual. These critics also see Francis’s papacy as flirting dangerously with paganism, pantheism, and even Marxism, because they view the pope’s emphasis on attending to the poor as often at odds with the exigencies of global capitalism.

The environment was the central focus of the meeting. In their final document, the bishops warned of the risks of deforestation, which they said now put almost 17 percent of the Amazon forest in danger, and also of the displacement of indigenous groups because of the deforestation. “Attacks on nature have consequences for the lives of peoples,” they wrote.

They defined what they called “ecological sins of commission or omission against God, against one’s neighbor, the community and the environment.” They called these “sins against future generations … manifest in acts and habits of pollution and destruction of the harmony of the environment, transgressions against the principles of interdependence and the ripping of network of solidarity among creatures and against the virtue of justice.”

In practical terms that means better coordination in the region for advocacy against environmental catastrophes, such as toxic spills related to mining, Bishop David M. De Aguirre Guinea, one of two special secretaries overseeing the synod, said at a news conference yesterday. “This has become part of the social doctrine of the Church, taking care of our common home,” he said.

Francis set the Amazon as the theme for the meeting three years ago, long before the devastating fires that swept through the region in August, the result of targeted deforestation to clear farmland. “The fires brought the thing home to us in a way that graphs or other visuals didn’t,” Cardinal Michael Czerny, a Canadian Jesuit and the other special secretary behind the synod, said. “If we insist on tearing up the trees and digging up the land because we can’t live without the metals and the gold and the wood for our fancy furniture, you can fill out the rest.”

Czerny is one of 13 new cardinals whom Francis appointed this month and who will one day elect his successor, the clearest way any pope shapes the future of the Church. Czerny, for instance, runs a Vatican office dedicated to migrants and refugees at the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, and his promotion is a clear sign of the importance Francis places on migration.

The pope also appointed other cardinals from the global South, making the College of Cardinals less white and less Italian. (One of the constant tensions of the Catholic Church is that it’s a global community of a billion souls governed at the top by an Italian village.)

Francis isn’t the first pope to open the door to some married priests. A decade ago, his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, created a special structure to allow married Anglican priests to join the Catholic Church. It was aimed at attracting Anglicans distressed by that Church’s ordination of women and gay priests, and it infuriated the then–Archbishop of Canterbury.

For the synod, Francis and the bishops framed the issue of married priests as stemming from a ground-up desire from some communities in the Amazon, not a top-down rule imposed by Rome, Alberto Melloni, the director of the John XXIII Foundation for Religious Studies in Bologna, told me. “It’s not a revolution,” he said. “It’s a late remedy to an evident call.”

The bishops didn’t vote to allow women to be ordained as deacons, but Francis, in his concluding remarks yesterday, said the Vatican would study the role of women in the early Church. “Women put out a sign that says, ‘Please listen to us, may we be heard,’ and I pick up that gauntlet,” the pope said to applause.

Francis also gave a special mention to Greta Thunberg, who has already become a kind of Joan of Arc for her time, and drawn no shortage of hatred—this month, police removed an effigy of Thunberg that had been hung from a bridge in Rome. In his concluding remarks yesterday, the pope spoke about the recent climate strikes by students around the world. “We’ve seen the demonstrations of young people, Greta and others, and they walk around saying ‘The future is ours, you can’t gamble with our future.’”

In one of the stranger sideshows of the synod, a handheld video circulated on a traditionalist Catholic website showing unidentified men removing several wooden figurines representing an Amazonian fertility figure from a Roman church and tossing the statuettes into the Tiber from the Ponte Sant’Angelo, lined with statues of angels and saints, against a perfect Roman sunrise. Some of Francis’s critics, such as Cardinal Gerhard Müller, a former head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican’s doctrinal office, seized on the video, and called the statuettes tantamount to idolatry. “The great mistake was to bring the idols into the church, not to put them out,” Müller said in an interview with an American conservative-Catholic TV channel, EWTN.

Francis, as bishop of Rome, apologized to his fellow bishops for the vandalism, and one of the statuettes was on view in the synod hall during the pope’s concluding remarks. A Mass today ending the synod included indigenous peoples from the Amazon. Francis’s approach to indigenous rites is “a very profound characteristic of the Jesuit missionary attitude,” Melloni told me, in which the Jesuits would try to convert native populations to Catholicism while also respecting the native traditions. “These rites express a culture and not a religion,” Melloni said.

But for Francis’s many critics, the statuettes, and the pope’s posing for photos in a feathered headdress, were further signs that the pope was watering down Church doctrine. These critics tend to be defenders of Benedict, a brainy disciplinarian who advocated a smaller, more doctrinally pure Church, rather than a more flexible and inclusive one.

“This synod is truly the most politically correct meeting of all time. It’s a relief that Greta Thunberg has not yet been chosen to be a cardinal,” Bishop Robert Mutsaerts of the Netherlands wrote in a blog post translated by LifeSite News, a conservative Catholic website that has been fiercely critical of Francis. “Is there anyone left who is actually worried about saving souls? But isn’t that why Christ died on the cross?”

“The bishops and cardinals are discussing the environment, the rise of the sea level; they are saying that above all, we should listen. They speak like politicians, using the same slogans, the same cheap rhetoric,” Mutsaerts wrote. Why? he asked. “It is not the specialty of the Church, it is not our core business and it is not our perspective.”

In the culture war between traditionalists and progressives over the future of the Church, the pope may be on the progressive, inclusive side, but his traditionalist critics have access to social media, which has an outsize influence in shaping perceptions. “We have a small, noisy minority and a large silent majority,” Melloni told me. “The noisy minority is struggling, with a certain success, to represent themselves as half of the Church, and they are not. They’re not even half the College of Cardinals, not even half the episcopate.”

In short, the Catholic Church on Twitter may not be the same as the Catholic Church writ large. Francis seems confident that he has the latter on his side, but will his efforts—on married priests, on environmentalism—spread beyond the Amazon?

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

On August 25 Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò published an eleven-page letter in which he accused Pope Francis of ignoring and covering up evidence of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church and called for his resignation. It was a declaration of civil war by the church’s conservative wing. Viganò is a former apostolic nuncio to the US, a prominent member of the Roman Curia—the central governing body of the Holy See—and one of the most skilled practitioners of brass-knuckle Vatican power politics. He was the central figure in the 2012 scandal that involved documents leaked by Pope Benedict XVI’s personal butler, including letters Viganò wrote about corruption in Vatican finances, and that contributed to Benedict’s startling decision to abdicate the following year. Angry at not having been made a cardinal and alarmed by Francis’s supposedly liberal tendencies, Viganò seems determined to take out the pope.

As a result of Viganò’s latest accusations and the release eleven days earlier of a Pennsylvania grand jury report that outlines in excruciating detail decades of sexual abuse of children by priests, as well as further revelations of sexual misconduct by Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington, D.C., Francis’s papacy is now in a deep, possibly fatal crisis. After two weeks of silence, Francis announced in mid-September that he would convene a large-scale gathering of the church’s bishops in February to discuss the protection of minors against sexual abuse by priests.

The case of Cardinal McCarrick, which figures heavily in Viganò’s letter, is emblematic of the church’s failure to act on the problem of sexual abuse—and of the tendentiousness of the letter itself. In the 1980s stories began to circulate that McCarrick had invited young seminarians to his beach house and asked them to share his bed. Despite explicit allegations that were relayed to Rome, in 2000 Pope John Paul II appointed him archbishop of Washington, D.C., and made him a cardinal. Viganò speculates that the pope was too ill to know about the allegations, but does not mention that the appointment came five years before John Paul’s death. He also praises Benedict XVI for finally taking action against McCarrick by sentencing him to a life of retirement and penance, and then accuses Francis of revoking the punishment and relying on McCarrick for advice on important church appointments. If Benedict did in fact punish McCarrick, it was a very well kept secret, because he continued to appear at major church events and celebrate mass; he was even photographed with Viganò at a church celebration.

Viganò’s partial account of the way the church handled the allegations about McCarrick is meant to absolve Pope Francis’s predecessors, whose conservative ideology he shares. Viganò lays the principal blame for failing to punish McCarrick on Francis, who does appear to have mishandled the situation—one he largely inherited. He may have decided to ignore the allegations because, while deplorable, they dated back thirty years and involved seminarians, who were adults, not minors. Last June, however, a church commission found credible evidence that McCarrick had behaved inappropriately with a sixteen-year-old altar boy in the early 1970s, and removed him from public ministry; a month later Francis ordered him to observe “a life of prayer and penance in seclusion,” and he resigned from the College of Cardinals. On October 7, Cardinal Marc Ouellet, prefect of the Congregation for Bishops at the Vatican, issued a public letter offering a vigorous defense of Francis and a direct public rebuke of his accuser:

Francis had nothing to do with McCarrick’s promotions to New York, Metuchen, Newark and Washington. He stripped him of his Cardinal’s dignity as soon as there was a credible accusation of abuse of a minor….

Dear Viganò, in response to your unjust and unjustified attack, I can only conclude that the accusation is a political plot that lacks any real basis that could incriminate the Pope and that profoundly harms the communion of the Church.

The greatest responsibility for the problem of sexual abuse in the church clearly lies with Pope John Paul II, who turned a blind eye to it for more than twenty years. From the mid-1980s to 2004, the church spent $2.6 billion settling lawsuits in the US, mostly paying victims to remain silent. Cases in Ireland, Australia, England, Canada, and Mexico followed the same depressing pattern: victims were ignored or bullied, even as offending priests were quietly transferred to new parishes, where they often abused again. “John Paul knew the score: he protected the guilty priests and he protected the bishops who covered for them, he protected the institution from scandal,” I was told in a telephone interview by Father Thomas Doyle, a canon lawyer who was tasked by the papal nuncio to the US with investigating abuse by priests while working at the Vatican embassy in Washington in the mid-1980s, when the first lawsuits began to be filed.

The greatest responsibility for the problem of sexual abuse in the church clearly lies with Pope John Paul II, who turned a blind eye to it for more than twenty years. From the mid-1980s to 2004, the church spent $2.6 billion settling lawsuits in the US, mostly paying victims to remain silent. Cases in Ireland, Australia, England, Canada, and Mexico followed the same depressing pattern: victims were ignored or bullied, even as offending priests were quietly transferred to new parishes, where they often abused again. “John Paul knew the score: he protected the guilty priests and he protected the bishops who covered for them, he protected the institution from scandal,” I was told in a telephone interview by Father Thomas Doyle, a canon lawyer who was tasked by the papal nuncio to the US with investigating abuse by priests while working at the Vatican embassy in Washington in the mid-1980s, when the first lawsuits began to be filed.

Benedict was somewhat more energetic in dealing with the problem, but his papacy began after a cascade of reporting had appeared on priestly abuse, beginning with an investigation published by the Boston Globe in 2002 (the basis for Spotlight, the Oscar-winning film of 2015). The church was faced with mass defections and the collapse of donations from angry parishioners, which forced Benedict to confront the issue directly.

Francis’s election inspired great hopes for reform. But those who expected him to make a clean break with this history of equivocation and half-measures have been disappointed. He hesitated, for example, to meet with victims of sexual abuse during his visit to Chile in January 2018 and then insulted them by insisting that their claims that the local bishop had covered up the crimes of a notorious abuser were “calumny.” In early October, he expelled from the priesthood two retired Chilean bishops who had been accused of abuse. But when he accepted the resignation of Cardinal Donald Wuerl—who according to the Pennsylvania grand jury report repeatedly mishandled accusations of abuse when he was bishop of Pittsburgh—he praised Wuerl for his “nobility.” Francis seems to take one step forward and then one step backward.

Viganò is correct in writing that one of Francis’s closest advisers, Cardinal Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga, disregarded a grave case of abuse occurring right under his nose in Honduras. One of Maradiaga’s associates, Auxiliary Bishop Juan José Pineda Fasquelle of Tegucigalpa, was accused of abusing students at the seminary he helped to run. Last June, forty-eight of the 180 seminarians signed a letter denouncing the situation there. “We are living and experiencing a time of tension in our house because of gravely immoral situations, above all of an active homosexuality inside the seminary that has been a taboo all this time,” the seminarians wrote. Maradiaga initially denounced the writers as “gossipers,” but Pineda was forced to resign a month later.

“I feel badly for Francis because he doesn’t know whom to trust,” Father Doyle said. Almost everyone in a senior position in the Catholic Church bears some guilt for covering up abuse, looking the other way, or resisting transparency. The John Jay Report (2004) on sexual abuse of minors by priests, commissioned by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, indicated that the number of cases increased during the 1950s and 1960s, was highest in the 1970s, peaking in 1980, and has gradually diminished since then. Francis may have hoped that the problem would go away and feared that a true housecleaning would leave him with no allies in the Curia.

Much of the press coverage of the scandal has been of the Watergate variety: what the pope knows, when he found out, and so forth. This ignores a much bigger issue that no one in the church wants to talk about: the sexuality of priests and the failure of priestly celibacy.

Viganò blames the moral crisis of the papacy on the growing “homosexual current” within the church. There is indeed a substantial minority of gay priests. The Reverend Donald B. Cozzens, a Catholic priest and longtime rector of a seminary in Ohio, wrote in his book The Changing Face of the Priesthood (2000) that “the priesthood is, or is becoming, a gay profession.” There have been no large surveys, using scientific methods of random sampling, of the sexual life of Catholic priests. Many people—a priest in South Africa, a journalist in Spain, and others—have done partial studies that would not pass scientific muster. The late Dr. Richard Sipe, a former priest turned psychologist, interviewed 1,500 priests for an ethnographic study.

There is some self-selection by priests who agree to answer questions or fill out questionnaires or seek treatment, which is why the estimates on, say, gay priests vary so widely. But the studies are consistent in showing high percentages of sexually active priests and of gay priests. As Thomas Doyle wrote in 2004, “Knowledgeable observers, including authorities within the Church, estimate that 40–50 percent of all Catholic priests have a homosexual orientation, and that half of these are sexually active.” Sipe came to the conclusion that “50 percent of American clergy were sexually active…and between 20 and 30 percent have a homosexual orientation and yet maintained their celibacy in an equal proportion with heterosexually oriented clergy.”

In his letter Viganò repeats the finding in the John Jay Report that 81 percent of the sexual abuse cases involve men abusing boys. But he ignores its finding that those who actually identify as homosexual are unlikely to engage in abuse and are more likely to seek out adult partners. Priests who abuse boys are often confused about their sexuality; they frequently have a negative view of homosexuality, yet are troubled by their own homoerotic urges.

Viganò approvingly cites Sipe’s work four times. But he ignores Sipe’s larger argument, made on his website in 2005, that “the practice of celibacy is the basic problem for bishops and priests.” Sipe also wrote, “The Vatican focus on homosexual orientation is a smoke screen to cover the pervasive and greater danger of exposing the sexual behavior of clerics generally. Gay priests and bishops practice celibacy (or fail at it) in the same proportions as straight priests and bishops do.” He denounced McCarrick’s misconduct on numerous occasions.

While the number of priests abusing children—boys or girls under the age of sixteen—is comparatively small, many priests have secret sex lives (both homosexual and heterosexual), which does not leave them in the strongest position to discipline those who abuse younger victims. Archbishop Rembert Weakland, for example, the beloved liberal archbishop of Milwaukee from 1977 to 2002, belittled victims who complained of sexual abuse by priests and then quietly transferred predatory priests to other parishes, where they continued their abusive behavior. It was revealed in 2002 that the Milwaukee archdiocese had paid $450,000 in hush money to an adult man with whom Weakland had had a longtime secret sexual relationship, which might have made him more reluctant to act against priests who abused children. But this could be true of heterosexual as well as homosexual priests who are sexually active.

Viganò believes that the church’s moral crisis derives uniquely from its abandonment of clear, unequivocal, strict teaching on moral matters, and from overly permissive attitudes toward homosexuality in particular. He does not want to consider the ways in which its traditional teaching on sexuality—emphasized incessantly by recent popes—has contributed to the present crisis. The modern church has boxed itself into a terrible predicament. Until about half a century ago, it was able to maintain an attitude of wise hypocrisy, accepting that priests were often sexually active but pretending that they weren’t. The randy priests and monks (and nuns) in Chaucer and Boccaccio were not simply literary tropes; they reflected a simple reality: priests often found it impossible to live the celibate life. Many priests had a female “housekeeper” who relieved their loneliness and doubled as life companions. Priests frequently had affairs with their female parishioners and fathered illegitimate children. The power and prestige of the church helped to keep this sort of thing a matter of local gossip rather than international scandal.

When Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council in 1962, bishops from many parts of the world hoped that the church would finally change its doctrine and allow priests to marry. But John XXIII died before the council finished its work, which was then overseen by his successor, Paul VI (one of the popes most strongly rumored to have been gay). Paul apparently felt that the sweeping reforms of Vatican II risked going too far, so he rejected the pleas for priestly marriage and issued his famous encyclical Humanae Vitae, which banned contraception, overriding a commission he had convened that concluded that family planning and contraception were not inconsistent with Catholic doctrine.

Opposing priestly marriage and contraception placed the church on the conservative side of the sexual revolution and made adherence to strict sexual norms a litmus test for being a good Catholic, at a time when customs were moving rapidly in the other direction. Only sex between a man and a woman meant for procreation and within the institution of holy matrimony was allowed. That a man and a woman might have sex merely for pleasure was seen as selfish and sinful. Some 125,000 priests, according to Richard Sipe, left the priesthood after Paul VI closed the door on the possibility of priestly marriage. Many, like Sipe, were straight men who left to marry. Priestly vocations plummeted.

Conversely, the proportion of gay priests increased, since it was far easier to hide one’s sex life in an all-male  community with a strong culture of secrecy and aversion to scandal. Many devout young Catholic men also entered the priesthood in order to try to escape their unconfessable urges, hoping that a vow of celibacy would help them suppress their homosexual leanings. But they often found themselves in seminaries full of sexual activity. Father Doyle estimates that approximately 10 percent of Catholic seminarians were abused (that is, drawn into nonconsensual sexual relationships) by priests, administrators, or other seminarians.

community with a strong culture of secrecy and aversion to scandal. Many devout young Catholic men also entered the priesthood in order to try to escape their unconfessable urges, hoping that a vow of celibacy would help them suppress their homosexual leanings. But they often found themselves in seminaries full of sexual activity. Father Doyle estimates that approximately 10 percent of Catholic seminarians were abused (that is, drawn into nonconsensual sexual relationships) by priests, administrators, or other seminarians.

This problem is nothing new. Homosocial environments—prisons, single-sex schools, armies and navies, convents and monasteries—have always been places of homosexual activity. “Man is a loving animal,” in Sipe’s words. The Benedictines, one of the first monastic orders, created elaborate rules to minimize homosexual activity, insisting that monks sharing a room sleep fully clothed and with the lights on.

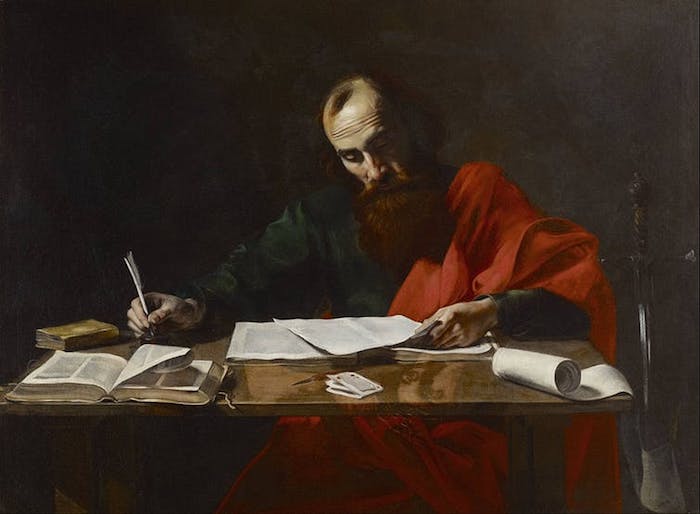

The modern Catholic Church has failed to grasp what its founders understood quite well. “It is better to marry than to burn with passion,” Saint Paul wrote when his followers asked him whether “it is good for a man not to touch a woman.” “To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain unmarried as I am. But if they are not practicing self-control, they should marry.” Priestly celibacy was not firmly established until the twelfth century, after which many priests had secret wives or lived in what the church termed “concubinage.”

The obsession with enforcing unenforceable standards of sexual continence that run contrary to human nature (according to one study, 95 percent of priests report that they masturbate) has led to an extremely unhealthy atmosphere within the modern church that contributed greatly to the sexual abuse crisis. A 1971 Loyola Study, which was also commissioned by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, concluded that a large majority of American priests were psychologically immature, underdeveloped, or maldeveloped. It also found that a solid majority of priests—including those ordained in the 1940s, well before the sexual revolution—described themselves as very or somewhat sexually active.

Sipe, during his decades of work treating priests as a psychotherapist, also concluded that the lack of education about sexuality and the nature of celibate life tended to make priests immature, often more comfortable around teenagers than around other adults. All this, along with a homosocial environment and the church’s culture of secrecy, has made seminaries a breeding ground for sexual abuse.

There are possible ways out of this dilemma for Francis. He could allow priests to marry, declare homosexuality to be not sinful, or even move to reform the patriarchal nature of the church—and to address the collapse in the number of nuns, which has decreased by 30 percent since the 1960s even though the number of the world’s Catholics has nearly doubled in that time—by allowing the ordination of women. But any of those actions would spark a revolt by conservatives in the church who already regard Francis with deep suspicion, if not downright aversion. John Paul II did his best to tie the hands of his successors by declaring the prohibition of female priests to be an “infallible” papal doctrine, and Francis has acknowledged that debate on the issue was “closed.” Even Francis’s rather gentle efforts to raise the possibility of allowing divorced Catholics who have remarried to receive the host at Mass was met with such strong criticism that he dropped the subject.

The sociology of religion offers some valuable insights into the church’s problems. One of the landmark texts in this field is the 1994 essay “Why Strict Churches Are Strong,” by the economist Laurence Iannaccone, who used rational choice theory to show that people tend to value religious denominations that make severe demands on them. The Mormon Church, for example, requires believers to give it a tenth of their income and a substantial amount of their time, abstain from the use of tobacco and alcohol, and practice other austerities. These costly demands create a powerful sense of solidarity. The commitment of time and money means that the church can undertake ambitious projects and take care of those in need, while the distinctive way of life serves to bind members to one another and set them apart from the rest of the world. The price of entry to a strict church is high, but the barrier to exit is even higher: ostracism and the loss of community.

Since the French Revolution and the spread of liberal democracy in the nineteenth century, the Catholic Church has been torn between the urge to adapt to a changing world and the impulse to resist it at all cost. Pope Pius IX, at whose urging the First Vatican Council in 1870 adopted the doctrine of papal infallibility, published in 1864 his “Syllabus of Errors,” which roundly condemned modernity, freedom of the press, and the separation of church and state. Significantly, its final sentence denounced the mistaken belief that “the Roman Pontiff can, and ought to, reconcile himself, and come to terms with progress, liberalism and modern civilization.” Since then the church has been in the difficult position of maintaining this intransigent position—that it stands for a set of unchanging, eternal beliefs—while still in some ways adapting to the times.

John XXIII, who became pope in 1958, saw a profound need for what he called aggiornamento—updating—precisely the kind of reconciling of the church to a changing world that Pius IX considered anathema. John XXIII was one of the high-ranking church leaders who regarded the Nazi genocide of the Jews as a moral crossroads in history. An important part of his reforms at Vatican II was to remove all references to the Jews as a “deicide” people and to adopt an ecumenical spirit that deems other faiths worthy of respect. After Vatican II, the church made optional much of the traditional window-dressing of Catholicism—the Latin Mass, the elaborate habits of nuns, the traditional prohibition against meat on Friday—but John died before the council took up more controversial issues of doctrine. With Vatican II, Iannaccone argued,

the Catholic church may have managed to arrive at a remarkable, “worst of both worlds” position—discarding cherished distinctiveness in the areas of liturgy, theology, and lifestyle, while at the same time maintaining the very demands that its members and clergy are least willing to accept.

Church conservatives are not wrong to worry that eliminating distinctive Catholic teachings may weaken the church’s appeal and authority. Moderate mainstream Protestant denominations have been steadily losing adherents for decades. At the same time, some forms of strictness can be too costly. The prohibitions against priestly marriage and the ordination of women are clearly factors in the decline of priestly vocations, and the even more dramatic decline in the number of nuns.

Both radical change and the failure to change are fraught with danger, making Francis’s path an almost impossible one. He is under great pressure from victims who are demanding that the church conduct an exhaustive investigation into the responsibility of monsignors, bishops, and cardinals who knew of abusing priests but did nothing—something he is likely to resist. Such an accounting might force many of the church’s leaders into retirement and paralyze it for years to come—but his failure to act could paralyze it as well. As for the larger challenges facing the church, Francis’s best option might be to make changes within the narrow limits constraining him, such as expanding the participation of the laity in church deliberations and allowing women to become deacons. But that may be too little, too late.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The recent report of widespread sexual abuse by priests in Pennsylvania has fueled increasing turmoil within the leadership of the Catholic Church. In July this year, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington, resigned following allegations against him.

Opponents of Pope Francis are urging him to resign in light of allegations that he knew about McCarrick’s behavior.

At a moment when a culture of secrecy, and what appear to be systematic cover-ups are leading to a crisis of faith, some people are asking whether priestly celibacy is at the root of these scandals.

The fact is for a long time the Catholic Church struggled with its interpretation of Scriptures on priestly celibacy. It wasn’t until the 12th century that priestly celibacy became mandatory.

In the middle of the first century, Paul, the most influential apostle of the early Christian movement, wrote a letter to a congregation of Jesus followers in Corinth, Greece. It contains the earliest record of a discussion about celibacy and marriage among “believers,” as Christians were called at the time.

Apparently, the members of the church had written to Paul what appears to be a simple and specific argument in favor of celibacy: “It is well for a man not to touch a woman,” they write. We do not know who wrote these words to Paul or why they made this claim.

But Paul’s response to their claims provides a basis for later Christian views on marriage and celibacy, sex and self-control, and ethics and immorality.

He writes,

“Because of cases of sexual immorality, each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband. The husband should give to his wife her conjugal rights, and likewise the wife to her husband. … Do not deprive one another except perhaps by agreement for a set of time, to devote yourselves to prayer, and then come together again, so that Satan may not tempt you because of your lack of self-control. This I say by way of concession, not of command.”

For Paul, marriage was a concession: He appears to view it reluctantly as merely an acceptable choice for those who cannot control themselves.

He goes on to say, “I wish that all were as I myself am,” implying at the very least that he is not married. And he confirms this in the passage that follows,

“To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain unmarried as I am. But if they are not practicing self-control, they should marry. For it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion.”

Marriage, in Paul’s view, is the lesser choice. It is for those who cannot control themselves. Although difficult, remaining unmarried and choosing celibacy, seems to be the higher ideal.

As a a scholar of early Christianity, I know that Scriptural interpretations are always dynamic; Scripture is read and understood by different Christians in different time periods and places. So, it is not surprising that a short time later, Paul’s writings found new meaning as asceticism – the practices of self-control that included fasting, celibacy, and solitude –began to spread within Christianity.

A second-century expansion on the story of Paul, The Acts of Paul and Thecla, a largely fictional story about Paul’s missionary efforts in what is now modern Turkey, casts Paul primarily as a preacher of self-control and celibacy. In this story, Paul blesses “those who have wives as if they have them not.”

Such a phrase may sound strange to modern readers. But as monasticism grew within Christianity, some married Christian couples were faced with a problem: They did not want to divorce their spouses, because Scripture spoke against divorce. And yet they wanted to choose the life of celibacy. So these Christians chose to “live as brother and sister,” or “to have wives as if they had them not.”

At the same time, stories of failures to keep vows of celibacy abounded: stories of monks and nuns who lived together and bore children, stories of monks who took mistresses, and stories about behaviors that today would be considered sexual abuse.

These stories emphasized that temptation was always a problem for those who chose celibacy.

In the Middle Ages, the celibacy of the priesthood became a source of conflict between Christians. By the 11th century, it contributed to the formal schism between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

But the issues were far from resolved. Divergent views on mandatory celibacy for priests contributed to the reform movements in the 16th century. Martin Luther, a leader of the Protestant Reformation, argued that allowing priests to marry would prevent cases of sexual immorality. He drew upon Paul’s letters for support of his views.

On the other hand, leaders of the Catholic Church’s “Counter-Reformation,” a reform and renewal movement that had begun before Martin Luther, did not advocate marriage, but sought to address corrupt practices among the clergy.

Desiderius Erasmus, for example, a 16th century Catholic scholar, wrote a powerful critique of corruption in the Catholic Church. His views may well have been shaped by the fact that he himself was the illegitimate son of a Catholic priest.

One of the most important developments in this period was the creation of the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits, which sought to reform the priesthood in the face of accusations of sexual relations and corruption by, in part, improving the education of priests. In the founding rules of the Jesuit order, emphasis was placed on the importance of celibacy, training and preparation for missionary work, and serving the directives of the pope.

Pope Francis too is a Jesuit and has a long church history and tradition that he could draw from. The question is, at a time when the church is facing a crisis, will he show the way towards renewal and reform?

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!