I wanted to keep him out of trouble with the Church, but he shows no evidence of wishing the same in this impassioned plea for love & justice

By James Finn

Fr. Andy Herman is a Roman Catholic priest who corresponds with me about LGBTQ issues. I have sometimes observed that Catholic priests are reluctant to publicly criticise Church teachings and practices.

Andy is a remarkable, refreshing exception. He offered to be interviewed. I asked him to write up a first-person story. This is it, after I edited and polished it. I wanted to keep him out of trouble with the Church, but he shows no evidence of wishing the same, which you’ll see in this impassioned, earthy plea for love and justice.

If this story inspires you, ask him for more, especially accounts of his youth rescue work in Los Angeles, which is hair-raising love in action.

Hi! My name’s Andy!

(“Hi Andy!” )

I’m bisexual!

(“Welcome, Andy!” [Applause.])

And I have been “intrinsically disordered” for… 74 years!

([Applause picks up, whoops & shouts of encouragement and congratulations.])

I know that’s tweaked a bit, because to be honest I’m not personally familiar with 12-step meetings. But the real problem is, it’s ass backwards.

My real name IS Andy. Andy Herman. Father Andy Herman. I’m a Roman Catholic priest.

I retired myself from public ministry with the institutional Catholic Church, because many years ago I vowed to make sure my mom and dad would never have to go into a nursing home as they declined in age. Which vow I was able to keep.

I was also canonically bounced out of my religious community, because I decided not to return to them while I was taking care of my parents. It was all very friendly. Honestly. I have the documentation to prove it.

But I’m not here to talk about me.

I am here to talk about the ass backwards garbage coming out of the Catholic Diocese of Marquette, Michigan.

I’m sure those of you who keep up with Catholic news know what I’m talking about. Members of the LGBTQIA+ community in that diocese have, in essence, been told to go eff themselves.

LGBTQ Catholics are not wanted in Upper Michigan in any way, shape, or form. They will not be permitted to take part in most (or any) of the sacramental and communal life of the Church.

What I do now is try to help homeless people on the street, most especially homeless kids, and really most especially, LGBTQ kids.

The Marquette Diocese is led by a Bishop whose name I will not utter, in the manner of news organizations not repeating the name of a perpetrator of a particularly terrible crime. That’s what’s going on in Upper Michigan — crimes against LGBTQIA+ people, especially Roman Catholics.

Let’s call him Bishop ID, Intrinsically Disordered, because that’s what the Catechism of the Catholic Church calls US. Or better yet, let me refer to him as Bishop AB. Sure you get that one right off.

I ranted about this situation in a letter to the Prism & Pen editors, when it was first reported here. I was told maybe I could pen something, but just shave off some of the rougher ranting edges. So, I think I’ve un-ranted pretty much, and also don’t want to go into some analysis that’s already been done.

I just want to present a couple of points to the people of Upper Michigan, especially those of you who may be LGBTQ+ Catholics, and, I guess, particularly to those of you who may want to remain in the Church.

Or not.

I’ll also presume that latter description is one that many of you have already answered. Like so many of us, you’ve already left a place where you’re not wanted.

Let me just briefly tell you what these points are, and, if you think they’re worth something, please share them if it’s at all appropriate, especially with young people who are on the LGBTQIA+ spectrum.

I grew up in Chicago and have been out here in Los Angeles for many years. What I do now is try to help homeless people on the street, most especially homeless kids, and really most especially, LGBTQ kids.

So I am sick and tired — to put it mildly — to have to, for the 3 millionth time in my life, explain THIS to kids who are of our community:

- There is not a damn thing wrong with you.

- God does love you, and Jesus never said an effing thing against you.

Period. But let me not rant further.

Let me, as a trained Roman Catholic priest, make the following points:

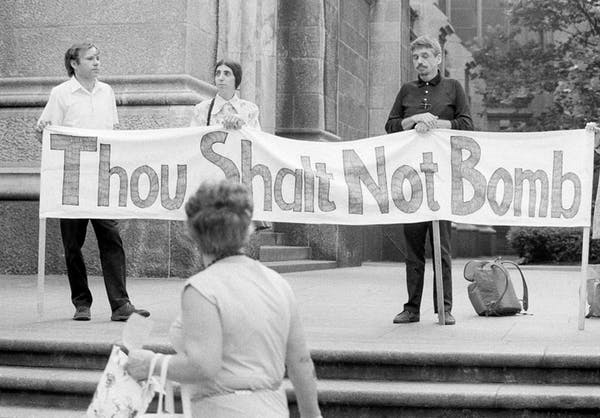

1.) Apparently, the Bishop of Marquette, and so many others like him, have spent not one moment praying, meditating, contemplating, experiencing, talking about, or studying anything of any consequence regarding the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

What the Bishop is perpetrating is utterly opposite to that Gospel. I’m wrong about a lot of things in life, but I damn well know what I just said is accurate. The only persons who are “intrinsically disordered” here are Bishop AB and his cohorts.

To my fellow LGBTQ people, I say continue to be safe, protect yourselves, and THRIVE in all the practical ways you can, especially you who are our children. Never be the victims of this garbage, inside or outside yourselves.

2.) Pope Francis has called for a two-year process of synodality, and especially asked that people whose voices are opposite to, or never heard in the context of the Catholic Church, be given a seat at the table to discuss where the hell the Church should be going in years to come.

So, if you have the inkling to, speak up and tell Bishop AB that the Pope has personally invited you to sit at the table and give, even if that giving is seen as opposing the traditional, death-encrusted way talking about our faith that our Catholic leaders have indulged in for far too long.

3.) What Bishop AB has done is absolutely and utterly in contradiction to the morality of the Gospel, and certainly to the best pastoral practice of Catholic Church teaching. More than anything, he stands in utter defiance of Pope Francis’ attitude, which puts caring about people in front of stagnant, dormant, full-of-crap definitions of dogma and Catholic practice.

Bishop AB has declared dangerous nonsense against our community in the Diocese of Marquette, and if you want to get involved, please, you should immediately contact the Office of the Apostolic Nuncio to the United States, Archbishop Christophe Pierre. Ask that a canonical investigation of Bishop AB be initiated, and ask that — if the findings are as accurate as they are publicly presented now, and he is in egregious violation of the teachings of Jesus Christ — that he be removed from office immediately.

With a sigh, I would also suggest that you might recommend an investigation to determine if Bishop AB is something like a “Bishop Roy Cohn,” a name I would give him if he, sadly, is a self-hating member of our community, just like the notorious lawyer on the national scene years ago.

Here is the Nuncio’s contact information:

Office: 202-333-7121Fax: 202-337-4036 Working Days and Hours: Monday through Friday, from 9:00 am until 4:30 pm

With…www.nuntiususa.org

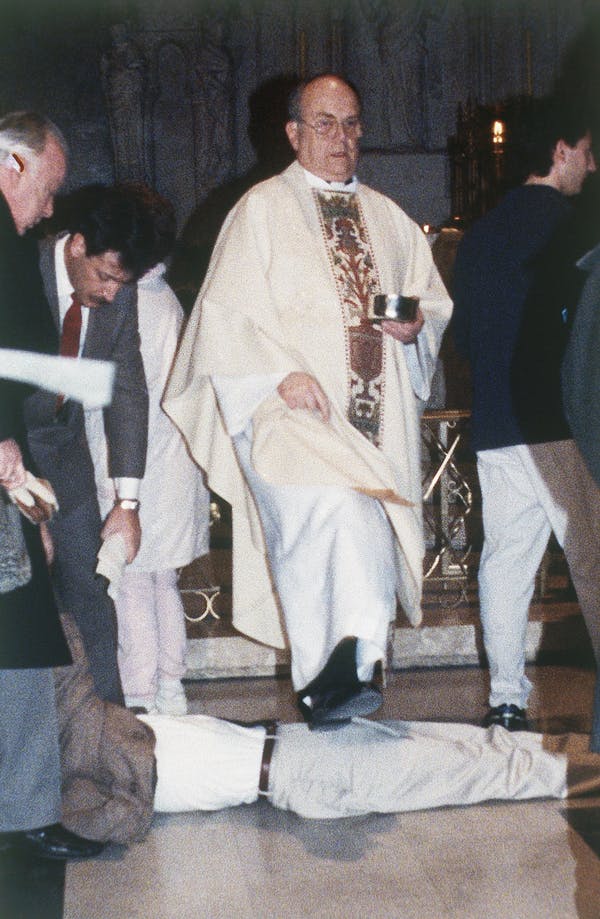

4.) No matter what you want to do, please always realize you don’t have to celebrate sacraments to get into heaven, if that’s the way you think about things, especially if the people who are supposed to guard the integrity of your “immortal soul” refuse you access to those very sacraments.

You can really get in contact with Jesus with the same surety as they supposedly offer, by simply sitting and praying — or gathering together with priests who have the cojones to offer Mass and celebrate the other sacraments, with and for you.

And if none of those “guys” up there in Michigan’s UP will do this, do it yourselves. Baptize one another. Confirm your kids reaching adulthood into belief that Jesus loves them. Forgive one another.

And most of all, consecrate bread and wine under the aegis that if two or three are gathered together in Jesus name, he is absolutely and uncontestedly present with and to you.

This is not BS passing for shallow theology. It is based in the Gospels.

5.) My last point is an old one from a most moldy and oldie traditional pastoral theology of the Sacrament of Penance, but it bears looking at. If a penitent is not able in some ways to recognize that he or she has sinned, or there are other confusions and concerns about whether or not the sins can be forgiven, a confessor can take upon himself the sins of the penitent, in order that the penitent be freed and given absolution.

So all of you LGBTQ people out there who make love, get married, and have great and loving sex, all of which are considered grievous sins by the Catholic Church, send the damn things over to me, because I sure as hell WILL accept them without any fear of ending up in hell myself. (If you even talk in language like that, because I don’t.)

Even if you don’t go to confession anymore, that’s my offer as a priest. Just sit down, get yourself into a state where you can think about these things, and send them over to me.

I will absorb them, and you are free to go about your normal, regular daily life. But please only do this if it really bothers you and you think that way. Otherwise, who cares?

Do you really think Jesus is sitting at the prosecutors’ table or even behind the bench as the judge, and wants to forgive you for stuff that, even to a nitpicker, isn’t worth being denied 10 nanoseconds of eternity without being completely wrapped up with God?

Remember who’s intrinsically disordered.

You may be an ass, you may be a jerk, you may be evil as hell, you may be lots of things, but you are not an evil person just because you are LGBTQ. You/We are exactly the opposite: we are the sons and daughters of a loving God, brothers and sisters of Jesus of Nazareth, the Anointed One.

If that’s how you want to phrase it.

The only kind of sex that is ever evil or sinful is coercive sex, otherwise known as assault and/or rape. That includes trafficking, but cannot include sex workers themselves, per se.

If someone is forced to do that to stay alive, or doing it for some negative psychological or emotional reason, the situation is evil, not the people forced into it. Gay, straight, or anywhere on the spectrum.

Let’s not get confused about this. Jesus never said anything about this.

Back when the early church sought to make itself more credible, it adopted certain forms of Greek philosophy, including this idea known as the “Natural Law.” Saint Thomas Aquinas adopted and pushed these ideas. He was apparently not a bad guy, but he cannot possibly stand in as a substitute for Jesus.

All that extra-Biblical natural law business, mixed up with the rather primitive prescriptions against any kind of same-sex anything, especially in the Jewish scriptures — well, that leads to the wondrously inhumane, tragically harmful attitudes and behaviors we see too often in the Church today.

Stay away from this thinking, these attitudes and actions.

Read the Gospel. Talk to people who don’t like being cruel and hateful to others, especially to kids. Band together with them. I think you’ll find that the brief analysis I’ve given here on these points is accurate.

Stay away from those who are the opposite, like Bishop AB and his followers. If you feel like telling them to go to hell, I don’t think it’s going to really matter because they may be on their way anyway.<

But everyone, even the most horrible sinners, can be forgiven. So I say, “Look in the mirror, Bishop AB.”

In the words of Pope Francis, “Who am I to judge?” I don’t know who any of you are in person, but I send you my love and my support and my prayer and I ask you, please — for me and most especially for the homeless LGBTQ youth I work with — to throw it all back at me.

In the name of Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God, Son of Man, or whoever you really think he is: Love one another, unconditionally, as he loves us.

Thanks for reading.

Fr. Andy Herman

***********************

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!