By Adam Gopnik

Critics of gay marriage often base their arguments on the certainty of their religious convictions. But societies without doubt are dangerous places, argues Adam Gopnik.

One of the strangest consequences of the recent Supreme Court decision here in the US – the one that made marriage between people of the same sex legal in all 50 states – is the amazing persecution mania it has engendered among religious people who don’t agree with it. They don’t just disagree with the decision, as of course they would. They feel threatened by it. They feel that the reality that men in San Francisco are now fighting over who should be first in line to rent formalwear has thrown them, the faithful, back into the catacombs, where they tremble at the tread of the legions and hear the distant roar of lions. They feel victims of a form of secular martyrdom that could easily bleed over into the real thing.

It’s hard to know why. No church has been closed, no temple shuttered, no sermon suspended. No-one who thinks that gay marriage is an abomination has been kidnapped and thrust, chained and dressed in leather, into the depths of a bar on Christopher Street. If you run a business that is open to the public, like a wedding caterer, then it does seem that you may have to cater for gay marriages along with straight, but that was a civil rights battle fought and won at the lunch counters of the American South 50 years ago. If you are open to the public, then you are open to the public, and have to take the public as it is, multi-coloured and many-sided and oddly angled.

Now, it has always been my view that gay marriage is the religious conservative’s best friend. If it is your aim to remove potentially subversive sex from the American scene, then marriage is always the answer. Indeed, if your goal was to stop gays from ever having sex again, then you ought to want to make gay marriage compulsory. But this essentially conservative decision creates an odd panic. What will come next, they cry? Polygamy, or legalised bestiality?

Well, all such “slippery slope” arguments are silly, because all social life takes place on a slippery slope. Once we have banned walking across the street when the red light is on, what is there to prevent us from imprisoning all pedestrians? When once we have a speed limit for cars, what is to prevent us from enforcing a rule of absolute stasis on every Volvo? Nothing, except all that protects us in any case, which is common sense and the experience of mankind. A law lowering the drinking age does not mean that some day soon all babies will have bourbon in their bottles, and gay marriage no more implies polygamy and bestiality and incest than a law against breaking and entering implies the abolition of windows and doors. The courts bless gay marriage now, in any case, because it was already blessed by our entertainments and its own peaceful existence. Manners make laws, and manners alone can repeal them.

No, what the opponents of gay marriage really cannot stand, I realise as I read them, is being criticised in the same spirit as they choose to criticise their opponents – not as holding a morality that might be too stringent to be obeyed, but holding a morality that was never really moral at all. Their complaint is, in its way, one that seems fixed in the political choices of the late Roman Empire. The only alternatives they can recognise as real are either power or persecution. Either you are the magistrate making rules, or else you are the martyr being sacrificed to them. This love of authority, and panic at its absence, is perhaps their central shaping conviction. This is why fundamentalist theologians tend not to mind hysterical atheists, who run around miserable at the loss of a super-deity, but do mind complacent atheists, who cannot see what the fuss was ever all about.

I have, I will confess, a certain intellectual sympathy with the believer’s position. There is a built-in contradiction between the claims of religion properly so-called, and those of a tolerant society. A religion in its nature, if it isn’t an ethic or worldview or philosophy (notice I didn’t say “merely” an ethic, since there’s nothing mere about those), makes astonishing cosmic claims about the nature and destiny of life itself, and usually about some supernatural incident in history. If you truly believe these claims with any degree of seriousness, then you are bound to believe that everything else retreats into insignificance before them. If I truly believed, say, as countless better writers than I once did, that the rulers of the world lived on a mountain in Greece and divided the realms and oceans among them and could be pleased and placated only by sacrificing heifers and rams and pigeons – well, I would be racing to Whole Foods to find a heifer to take out. No pigeon on the Manhattan street would be safe.

We’ve learned, though, by painful experience over the millennia, that ceding control of human life to those beliefs is catastrophic – as we see every day in the Middle East, where the “true believers” of IS give us a indelible picture of what rule by pure unrestrained, urgent belief actually looks like. Those who slaughter heifers to the benefit of their gods are soon slaughtering people to the same good cause. So, as much by clandestine co-operation as by any declaration, we have learned how to remove absolute belief from the seat of secular power.

But it has been done, and must be done, gently – the dispossession of faith from power is a long and slow one. The best books on how religious toleration came to the Western world rightly emphasise that they did not come in the spirit of religious conversions, in wild waves of enthusiasm and ideological conviction. Tolerance came slowly, and more often in the form of uneasy working truces than open sieges and surrenders. A painful practice of grudging co-existence created time for reflection – and the peace provoked the possibility that maybe the cosmic truths were neither quite so cosmic nor quite so true as they might have seemed.

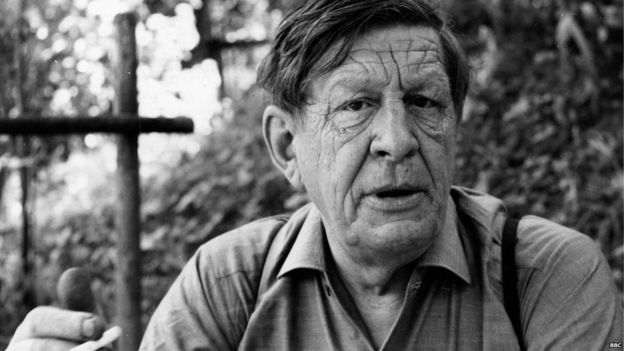

What people forget now, I think, is that in the middle of the terrible 20th Century there was a kind of religious revival among the most humane poets and philosophers – I think of WH Auden, of TS Eliot, of Simone Weil and Dietrich Bonheoffer. The reason was simple. They wanted to reaffirm the sanctity of individual conscience in a time of genuine totalitarian coercion – the real thing, with camps and gulags, not a fantasy of it consisting of mean things being said about you on Twitter. Some of them longed for authority to be re-established, and pined for old popes and Byzantine emperors. But the best – I think particularly of Auden, a gay man after whom I named my own son – turned to an idea of divinity because they thought it the best way of doubting the dictators. To keep a conscience, Auden thought, one must at least imagine a soul. Auden turned to faith because, by making the individual’s inner life paramount, it seemed a form of dissent from a mass society devoted to warping all those outer selves. Mass society wanted to take the soul out of the self, and faith could pop it back in.

WH Auden

- Wystan Hugh Auden (1907-1973) born in York and educated at Oxford University. Published his first volume of poems in 1930

- His left-wing political sympathies inspired him to go to Spain in 1937 to observe the Spanish Civil War. In 1939 he was accused of fleeing danger when he emigrated to the US on the verge of World War Two

- In New York, Auden met the poet Chester Kallman who would be his companion for the rest of his life. He taught at a number of US universities and took citizenship in 1946

- Auden’s most famous poems include In Memory of WB Yeats, The Unknown Citizen and “Stop All The Clocks…” which was quoted at length in the 1994 film Four Weddings And A Funeral

But these people of faith were too busy doubting themselves to be furious at those who doubted them. Auden knew how little we know by observing the consequences of people in power who thought they knew it all: “There can be no ‘We’ which is not the result of the voluntary union of separate ‘I’s’,” he wrote.

A crucial third term intervenes between power and persecution – and that is, simply, pluralism. Pluralism is a not a weak doctrine, but a radical one. It accepts the truth of all those “I’s. Though science has given us genuine certainty about a great deal of celestial and human conduct – we know that men and women sprang from apes, as we know that gun laws limit gun violence – science cannot give us any certainty at all about ends, about what we ought to feel and how we ought to live. We know for certain that men and women sprang from apes but each of us must choose how to land that leap. At least pluralistic societies that accept many ways of seeing the world have tended to let us see inside our plural selves. Cults of certainty can only persecute or be persecuted. Communities of common doubt can always co-exist.

Complete Article HERE!